Research

Physics has been largely successful in using models to describe the behaviour of our world. The two major theories of the twentieth century – quantum mechanics and general relativity – have combined (though maybe not together) to help us understand everything from the origins of the universe to the composition of molecules and atoms.

One very nice explanation of this was given by Philip Anderson, and well summarized by the title of his paper, “More is different.” [Science, 177, 393 (1972)]. A metaphor I like to use in explaining this is that of “atoms in community” -- that together, individual particles can do much more together than they can alone.

Quantum simulation

One of the outstanding questions in the general field of quantum mechanics remains -- how to individual quantum particles come together to exhibit new and interesting collective or many-body behaviours? Why and how does their behaviour change when they are together?

While we have good models for how some systems work, there remain a great many whose microscopic origins we do not understand. How do these atoms come together to exhibit macroscopic properties, and are there new kinds of phenomena we can create by engineering our quantum particles’ interactions and environments?

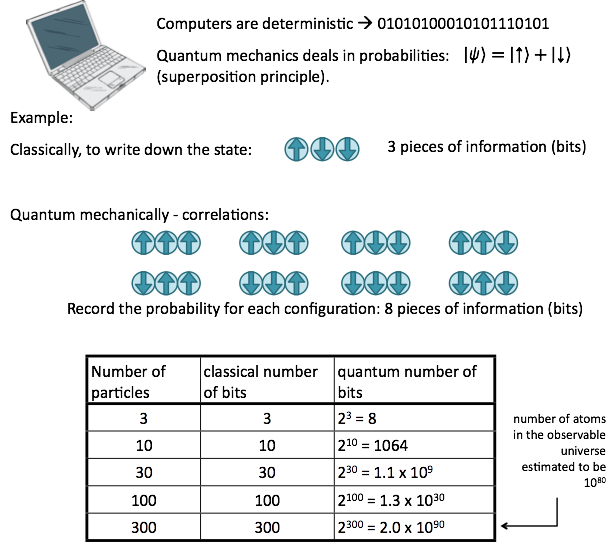

Traditional methods of creating models in physics have proven successful in all kinds of fields, but some limitations remain, especially when it comes to studying many-body systems, especially when those bodies are fermions. One might think that with a large enough computer, any properties should be able to be derived from first principles. Quantum mechanics makes this difficult -- the notion that things can exist in superposition must be accounted for, and when the number of particles becomes large, the possibilities for these superpositions exponentially increase, making calculations of even small numbers of particles impossible.

Richard Feynman was one of the first people to start talking about how one might exploit quantum mechanical systems to study quantum mechanical properties, to use the superpositions that naturally exist to store the information about the correlations quantum mechanically. In a speech he gave in 1982 [Int. J. Theo. Phys. 21, 467 (1982)], he finishes by saying:

-

“… nature isn’t classical dammit, and if you want to make a simulation of nature, you’d better make it quantum mechanical, and by golly, it’s a wonderful problem, because it doesn’t look so easy.”

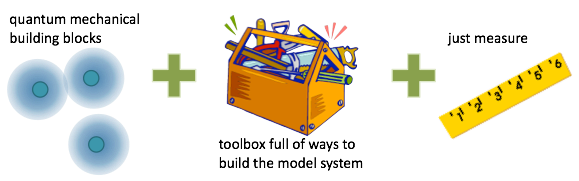

With this principle, we will simulate quantum mechanical many-body systems using the tools of atomic systems to design the interactions and environments -- the Hamiltonians -- for our quantum mechanical atoms. To do this, we need a system with quantum degrees of freedom (our cold atoms) and ways to manipulate them (the cold-atom toolbox). We then let the system evolve under Nature’s rules, and measure the results we get, the solutions of our analogue calculation.

For some recent discussions of the advances and prospects for quantum simulation, see the following reviews:

“Many-body physics with ultracold gases,” Bloch, Dalibard, Zwerger, Rev. Mod. Phys., 80, 885 (2008). [arxiv]

“Simulation: Quantum leaps,” Brumfiel, Nature 491, 322 (2012).