Conclusions

While the statistical

analysis of the project data presented a valid result, on the basis of

the data meeting the assumptions of the statistical test

applied, the presented results are of limited value because of

flaws in experimental design. Because water is a flowing medium,

land uses and cattle presence upstream contribute E.coli to water

sampled from the treatment area. The location of the treatment

(fencing) site downstream of the control/background site (upstream)

presents a difficulty because the water quality observed at the fencing

treatment represents the cumulative E.coli load of both the upstream

area where cattle have access to the channel and the treatment reach

where cattle have no access. The proximity, small size and

relative locations of the fencing treatment area and

background/unfenced area indicate that the two treatments are

not truly independent of one another.

Independence is a fundamental requirement for inferential

statistics; as such, the comparison of E.coli means using a t test is

not valid.

To see a difference in the mean E.coli between the

background level and that following the stream's passage through the

fencing treatment area, the length of treatment reach would need to be

adequate to allow natural attenuation of E.coli, or the treatment reach

would need to have some biological function capable of reducing

E.coli. The predicted effect of the fencing treatment is to

limit direct E.coli deposition directly to the stream, not to modify

instream habitat. The length of the treatment reach, 800 m, given

flow conditions, is likely not long enough to remove the effect of

E.coli entering the treatment area from

upstream. Additionally, the fenced treatment is unreplicated

in both space and within each temporal period, so I would be

unable to expand any findings to a broader population (i.e., beyond the

one study stream to agricultural watercourses in southern Alberta or to

other years).

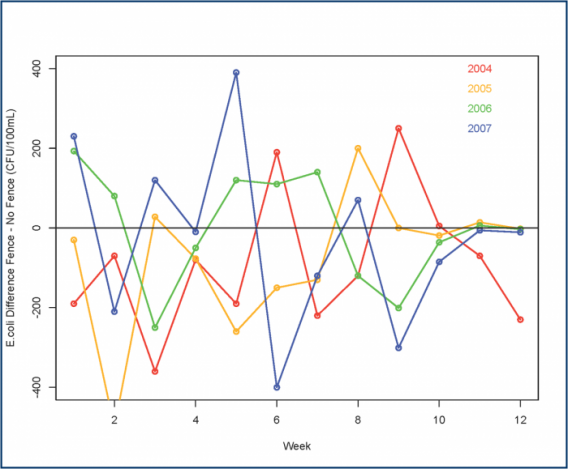

No uniform effect on E.coli concentration was

observed with the fencing treatment from week to week. As can

be seen in Figure 15, from week to week throughout the study

period, E.coli concentrations shifted from a positive

difference between treatments (suggesting an increase in E.coli

after fencing) to a negative difference (suggesting a decrease in

E.coli after fencing).

Figure 15. Confounded treatment effects visible in comparison of weekly differences in E.coli between fenced and non-fenced sites, 2004 to 2007. Positive differences indicate an increase in E.coli concentration after the fencing treatment is applied, while negative differences indicate a decrease in E.coli concentration after the fencing treatment.

The original question,

does exclusion fencing reduce E.coli concentrations in streams,

cannot be adequately answered by this research program because of these

flaws in experimental design. No significant difference (a=0.05)

was observed between mean log E.coli concentrations of the fenced and

unfenced treatments for 2004 to 2007, but I cannot infer

any conclusion regarding the efficacy of the fencing

treatment at reducing E.coli in streams. The lack of

independence between the treatments invalidates any

inferential statistical analysis.

Benefits to future study of

the research watercourse and watershed may be drawn from the this work

through the decriptive analysis of natural variation of water quality

(in this case, E.coli concentrations) within the channel.

Understanding seasonal and annual variation in water quality from

2004 to 2007 forms a baseline for future comparisons of

impacts of landscape or climate changes and supports further, more

rigorously designed, experimentation to study the effects of

agricultural land use changes.