|

The Learning Organization

Based on:

The Fifth Discipline:

The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization

Peter

Senge, 1990

Yonatan Reshef

School of Business

University of Alberta

Edmonton, Alberta

T6G 2R6 CANADA

MENU

Introduction

The Laws of

the Fifth Discipline

Personal

Mastery

Mental Models

Shared

Visions

Team Learning

-

Slides

System thinking is the Fifth Discipline. The other four disciplines are:

personal mastery, mental models, shared visions, and team learning. The

first two are oriented to the individual and the last two are oriented to

groups. Systems thinking has the distinction of being the "fifth

discipline" since it serves to make the results of the other disciplines work

together for business benefit.

- Business and other human endeavors are

systems. They are bound by invisible fabrics of

interrelated actions, interactions, values, norms and shared understandings which often

take years to fully play out their effects on each other.

- One can only understand such systems by contemplating the

whole, not any individual part

of the pattern. Frequently, since we are part of the system, it is very difficult to see

the whole pattern of effects. Instead, we tend to focus on snapshots of isolated parts of

the system, and wonder why our deepest problems never seem to be solved.

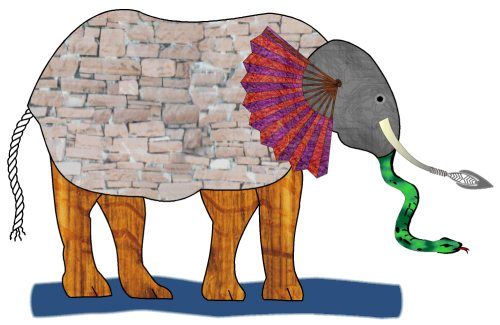

An

Elephant Story

Did you hear the story

about three blind men and the elephant?

The

first blind man touched the elephant's leg and

exclaimed, ''This animal is like a huge tree!''

The

second blind man happened to hold onto the

elephant's tail and rejoined: ''No, this animal is

like a snake!''

The

third blind man protested: ''You're both wrong! This

animal is like a wall.'' (He was touching the

elephant's flank.)

Each blind man thinks he is right and the others are

wrong, even though all three of them are all touching

the same elephant.

|

Systems thinking is a conceptual framework,

a body of knowledge and tools that has been

developed to make full patterns clearer, and to help us see how to change them

effectively. It helps us answer the question -- how have we created what we currently

have?

Definition.

According to Senge (p. 3),

|

Learning organizations are organizations

where people continually expand their capacity to create the results

they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are

nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are

continually learning how to learn together. |

Others argue that the

range of organizational learning conceptualization varies due to

both discipline and focus: as knowledge acquisition; as adaptation;

as skill learning; as development of shared knowledge base; as

development of shared assumptions, and; as institutional know-how

(Mitki, Shani, and Meiri. 1997. Journal of Organizational Change

Management: 428).

According to Garvin (HBR, July-August, 1993: 80), "a learning

organization is an organization skilled at creating, acquiring, and

transferring knowledge, and at modifying its behavior to reflect new knowledge

and insights."

He goes on and explains that his definition starts with a simple truth: new

ideas are essential if learning is to take place. Sometimes they are

created anew; at other times they arrive from outside the organization or are

communicated by knowledgeable insiders. Whatever their source, these

ideas are the trigger for organizational improvement. But they cannot by

themselves create a learning organization. Without accompanying

changes in the way that work gets done, only the potential for improvement

exists.

Learning organization -- An

organization that acquires new knowledge and translates it into new ways of

behaving.

Building Blocks

Systematic problem solving

Systematic problem solving

Experimentation with new approaches

Experimentation with new approaches

Learning

from own experiences Learning

from own experiences

Learning

from the experiences and best practices of others Learning

from the experiences and best practices of others

Transferring knowledge quickly and efficiently throughout the organization

Transferring knowledge quickly and efficiently throughout the organization

- Today's problems come from yesterday's "solutions." Solutions that

merely shift problems from one part of a system to another often go undetected because,

those who "solved" the first problem are different from those who inherit the

new problem (Examples: resistance to antibiotics; kids watching too

much TV; a need to close down hospital beds; a new government

dealing with the problems created by its predecessor.)

- The harder you push, the harder the system pushes back. The more effort you

expend trying to improve matters, the more effort seems to be required. This phenomenon is

called "compensating feedback." (Examples: pushing TQM on

workers; educating children.)

- Behavior grows better before it grows worse. Compensating feedback usually

involves a "delay," a time lag between the short-term benefit and the long-term

disbenefit. In complex human systems there are always many ways to make things look better

in the short run. Only eventually does the compensating feedback come back to haunt you.

(Examples: layoffs; punishing people.)

- The easy way out usually leads back in. We all find comfort applying familiar

solutions to problems, sticking to what we know best. Pushing harder and harder on

familiar solutions, while fundamental problems persist or worsen, is a reliable indicator

of nonsystemic thinking. We need a new type of action rooted in a new way of thinking.

(Examples: budget cuts; early retirement programs.)

- The cure can be worse than the disease. The long-term, most insidious consequence

of applying nonsystemic solutions is increased need for more and more of the solution

(Example: narcotic effects -- heavy reliance

on arbitrators and mediators to resolve industrial relations

disputes.)

- Faster is slower. The optimal rate is far less than the fastest possible growth.

(Examples: building a new sport team by buying the best players you

can get with your money; drive very fast and cause an accident.)

- Cause and effect are not closely related in time and space. There is a

fundamental mismatch between the nature of reality in complex systems and our predominant

ways of thinking about the reality. The first step in correcting that mismatch is to let

go of the notion that cause and effect are close in time and space (Examples: the effects of

parents' behaviors on children; laying off nurses and teachers to

cope with tough economic times; extensive use of antibiotics).

- Small changes can produce big results -- but the areas of highest leverage are often

the least obvious. Systems thinking shows that small, well-focused actions can

sometimes produce significant, enduring improvements, if they are in the right place.

Systems thinking refers to this principle as "leverage." There are no simple

rules for finding high-leverage changes, but there are ways of thinking that make it more

likely. Learning to see underlying "structures" rather than "events"

is a starting point; thinking in terms of processes of change rather than

"snapshots" is another (Examples: you get a big result for

just being nice/fair to people.)

- You can have your cake and eat it too -- but not at once. Many apparent dilemmas,

such as central versus local control, appear as rigid "either-or" choices,

because we think of what is possible at a fixed point in time. Next month, it may be true

that we must choose one or the other, but the real leverage lies in seeing how both can

improve over time. (Examples: When implementing TQM, you have

to adopt a long-term view; spending money on education/self

development = long-term investment.)

- Dividing an elephant in half does not produce two small elephants. Living systems

have integrity. Their character depends on the whole. The same is true for organizations;

to understand the most challenging issues requires seeing the whole system that generates

the issues. The key principle here is that the interactions that must be examined are

those most important to the issue at hand, regardless of parochial organizational

boundaries. (Examples: In a soccer/hockey team, you cannot improve

the team by working only with the forwards/defensemen; managing a

department.)

- There is no blame. Systems thinking assumes that there is no outside

circumstances to blame for your problems; that you and the cause of your problems are part

of a single system. The cure lies in your relationship with your "enemy"

(Example: low course evaluations.)

II. Personal Mastery

(139-173)

Personal mastery (PM) is the discipline of personal growth, learning and emotional

development. PM involves seeing one's life as a creative work, being able to clarify what

is really important, and learning to see current reality more clearly. Organizations

should thus enable individuals to approach their lives as a creative work, and to live

life from a creative as opposed to reactive viewpoint. PM requires organizations to

absolutely, fully, intrinsically commit themselves to the well-being of their people.

People with high level of personal mastery are continually expanding their ability to

create the results in life they truly seek.

|

The ability to focus on ultimate intrinsic desires (e.g. I want to be proud in what

I do), not only on secondary goals (e.g. I want to get 9 in this course), is a cornerstone

of PM. |

PM means that:

- People continually clarify what is important to them (they hold a personal vision)

- People continually learn how to see current reality more clearly

Creative tension

The juxtaposition of vision (what we want) and a clear picture of current reality

(where we are relative to what we want) generates "creative tension." In

other words, the difference between what's important, what we want, and where we are now

produces a creative tension. Creative tension is a force that aims to bring vision and

reality together. The essence of PM is learning how to generate and sustain creative

tension in our lives, understanding that the

journey is more important than "arriving." Put differently, mastery of creative tension transforms the way one

views "failure." Failure is, simply, a short fall, evidence of the gap between

vision and current reality. Failure is an opportunity for learning -- about inaccurate

pictures of current reality, about strategies that didn't work as expected, about the

clarity of the vision.

Unfortunately, often, when our vision is at odds with current reality we experience a "structural

conflict." This conflict is structural because it is a result of a structure of

conflicting forces: pulling us simultaneously toward and away from what we want. There are

several strategies to cope with structural conflicts:

1. Letting our visions erode;

2. Engaging in "conflict manipulation" -- using fear to pressure ourselves or

others to pursue a target more aggressively or avoid it altogether (negative visions);

and

3. Applying excessive willpower -- they try to overpower all forms of resistance to

achieving their goals.

All three strategies are an anathema to the discipline of PM.

Instead, we should understand the causes of problems. The first critical task

in dealing with structural conflicts is to recognize them, and the resulting behavior,

when they are operating. In other words, we must continually clarify to ourselves

why our

situation is the way it is. Structures of which we are unaware hold us prisoner. Once we

can see them and name them, they no longer have the same hold on us.

Then, structural conflicts are likely to give way to creative tension.

Why PM?

People with high levels of personal mastery are more committed. They take more

initiative. They have a broader and deeper sense of responsibility in their work. They

learn faster.

Summary

PM is about learning to keep both a personal vision and a clear picture of the current

reality. It is about understanding where you want to be, where you are

at present, the sources of the gap, and what how you can deal with it

emotionally and practically.

We can only set up conditions which encourage and support people who want to

increase their own personal mastery. Why offer such encouragement and support?

Organizations learn only through individuals who learn (but remember, individual learning

does not automatically translate into organizational learning). And, it is increasingly

clear that learning does not occur in any enduring fashion unless it is sparked by

people's own ardent interest and curiosity. If people only compliantly accept training in

statistical process control, team work, leadership, etc., the effects of this training

last for a while. But, if training is related to a person's own vision, then that person

will do whatever he or she can to keep learning.

Therefore, organization leaders should work relentlessly to foster a climate in which

the principles of personal mastery are practiced in daily life. That means, building an

organization where it is safe for people to create visions, where inquiry and commitment

to the truth are the norm, and where challenging the status quo is expected -- especially

when the status quo includes obscuring aspects of current reality that people seek to

avoid. However, an organizational commitment to personal mastery would be naive and

foolish if leaders in the organization lacked the capabilities of building shared vision

and shared mental models to guide local decision makers.

|

Remember, organizational learning

occurs through individual learning; yet not every individual learning

results in organizational learning. |

We define mental models, or paradigms, as the rationalities developed by organizational

groups to make sense of their work experiences (an interpretive

schemata that help people assign meaning to events). TQM is often radically different from

existing managerial approaches and, consequently, challenges prevailing control-based

paradigms in regard to how the organization should be run. A preliminary required condition for

successful TQM implementation is that the paradigm shift be championed and orchestrated by

top managers (Deming, 1986; Ishikawa, 1985; Jacob, 1993). Yet to be effective, the new

paradigm requires significant consensus and acceptance of its associated goals, values and

underlying assumptions by all organization members. In other words, effective

implementation of TQM must make sense to everyone involved, not just managers.

Accomplishing paradigm shifts is difficult. While paradigms are essential guides to

action they also exert powerful inertial forces that militate against a smooth change

process. Rather than immediately accepting a new perspective, even when there are problems

with an old one, people often try to fit ambiguous information into their existing

paradigm to preserve their existing cognitive structures (Bartunek, 1984; Murray &

Reshef, 1988; Barr, Stimpert & Huff, 1992). Consequently, quality "programs

presented as radical departures from the organization's past fail because the cognitive

structures of members, whose cooperation is necessary for successful implementation,

constrain their understanding and support of the new initiatives" (Reger et al.,

1994: 566).

For example, under traditional Taylorist management, employees have been part of a work

system extolling values such as division of labor, unilateral decision making, status

distinctions, reward for individual performance, and employment at will. An employee

paradigm compatible with this work system likely includes convictions such as, management

behaviors are self-driven in pursuit of profits, entitlements, and status (Ryan &

Oestreich, 1991: 85-99). Therefore, employees have little in common with management, and

should stay away from management decision making (Murray & Reshef, 1988).

These pre-existing convictions thus act as powerful interpretive filters. Interpretive

filters affect the precision with which a transmitted TQM message validly conveys the

desired meaning. Such filters render some management TQM activities legitimate and

acceptable. Others may be considered as attempts to "get more for less," and

hence arbitrary and unacceptable. The greater the distance between the

new, TQM, and employee

paradigms, the greater the likelihood that the TQM practices will be unacceptable to

the employees.

During the initial phase of the TQM implementation process, management and employees

might operate out of distinctly separate paradigms regarding the TQM intervention. They

would have their own understandings of the important variables involved in the change, and

their own perceptions of the likely sequence of events once new practices are initiated.

Given the premium TQM writers put on management-worker trust, cooperation, and consensual

decision making, a successful transition to TQM will remain elusive as long as employee

interpretations of TQM remain anchored in a management control philosophy.

Managing Paradigm Changes

How can management persuade employees who have not been socialized into a TQM system to

"pull" in the TQM direction, to identify with the TQM organization and its

goals, and to wish to facilitate these goals? How should management encode its TQM message

to account for different interpretive filters the employees may use?

Kurt

Lewin's Approach to Paradigm Change

The process whereby paradigms are altered and new understandings are developed is

clarified by Lewin's (1947) unfreezing, moving,

and

refreezing characterization.

During the unfreezing stage, management has to shake out old employee convictions to make

way for new ones. At this stage, management should articulate and rationalize the new, TQM

organizational order. Once old convictions are unfrozen and discarded, new understandings

about roles, responsibilities and relationships can be achieved. New convictions

ultimately become "frozen" as they are supported by the occurrence of

anticipated events (Barr, Stimpert & Huff, 1992).

Rousseau's Approach

to Paradigm Change

(she uses the term "contract" instead of paradigm. Academy of Management Executive, 1996, Vol. 10, 1, 50-59)

|

STAGE |

INTERVENTION |

CHALLENGING THE OLD CONTRACT

Stress Stress

Disruption

Disruption |

1. Provide new discrepant information (educate

people).

Why do we need to change? |

PREPARATION FOR CHANGE

Ending

old paradigm Ending

old paradigm

Reducing

losses Reducing

losses

Bridging

to new paradigm Bridging

to new paradigm |

1. Involve people in information gathering

(send them out to talk with customers and benchmark successful firms)

2. Interpret new information (show videos of customers describing

service and let employees react to it)

3. Acknowledge the end of the old paradigm (celebrate good features of

old paradigm)

4. Create transitional structures (cross-functional task forces to

manage change) |

PARADIGM GENERATION

Sense

making Sense

making

Veterans

become "new" Veterans

become "new" |

1. Evoke "new paradigm" script (have people sign on

to "new company" by completing an orientation session; clearly

outline new expectations and commitments)

2. Make paradigm makers (managers) readily available to share

information

3. Encourage active involvement in new paradigm creation |

LIVING THE NEW PARADIGM

Reality

checking Reality

checking |

1. Be consistent in word and action (train everyone

in new terms)

2. Follow through (align managers, human resources practices, etc.)

3. Refresh (re-emphasize the mission and new paradigm frequently)

|

Senge's Approach

to Paradigm Improvement

How Can We Align

Our Beliefs with Our Practices?

Senge suggests (Ch. 10) a different scheme to manage paradigm shifts --

surfacing, testing, and

improving. To be able to manage paradigms, people have to acquire several

skills:

- People should acquire the ability to recognize "leaps of abstraction."

Leaps of abstraction occur when we move from direct observation (concrete data) to

generalization without testing (e.g., all students are lazy people

who want to get good marks by doing minimum work). Leaps of abstraction impede learning because they become

axiomatic. What was once an assumption becomes treated as fact. To avoid leaps of

abstraction, ask yourself: What are the data on which this generalization is based? Where

possible, test the generalization directly.

- Left-hand column. This technique reveals ways that we manipulate situations to

avoid dealing with how we actually think and feel, and thereby prevent a counterproductive

situations from improving. This exercise compares "what one's thinking" with

"what is said/done." The left-hand exercise always succeeds in bringing hidden

assumptions to the surface and showing how they influence behavior. By not squarely facing

our problems, we undermine opportunities to learn in conflictual situations. There is no

one "right" way to handle difficult situations, but it helps to see how

one's own reasoning and actions can contribute to making matters worse.

"Openness" and "merit" are needed if one is to learn how to manage

one's mental model.

- Balancing inquiry and advocacy. Most managers are trained to be advocates. But

when managers need to tap insights from others, their advocacy skills become

counterproductive; they can close us off from actually learning from one another. As each

side reasonably and calmly advocates his viewpoint just a bit more strongly, positions

become more and more rigid. Advocacy without inquiry begets more advocacy. Simple

questions such as, "What is it that leads you to that position?" and "Can

you illustrate your point for me?" can introduce an element of inquiry into a

discussion. Yet, pure inquiry is also limited. The reason being, we almost always do have

a view. The most productive learning usually occurs when managers combine skills in

advocacy and inquiry. When operating in pure advocacy, the goal is to win the argument

(prove a point).

When inquiry and advocacy are combined, the goal is no longer "to win the

argument" but to find the best argument.

- Espoused theory vs. theory-in-use. Here, the problem lies not in the gap but in

failing to tell the truth about the gap. Until the gap between one's espoused theory and

one's current behavior is recognized, no learning can occur.

Entrenched mental models

will thwart changes that could come from systems thinking. Managers must learn to reflect

on their current mental models -- until prevailing assumptions are brought into the open,

there is no reason to expect mental models to change, and there is little purpose in

systems thinking.

A shared vision is a shared "picture of

the future." It is an organizational master plan which directs the organization's

members. A shared vision is not an idea. It is not even an important idea such as freedom.

It is, rather, a force in people's hearts, a force of impressive power. A shared vision is

the first step in allowing people who mistrusted each other to begin to work together. It

creates a common identity. In fact, an organization's shared sense of purpose, vision, and

operating values establish the most basic level of commonality. With a shared vision, work

becomes part of pursuing a larger purpose embodied in the organizations' products or

services.

The problem: It may simply not be possible to convince human beings rationally to

embrace

a long-term view.

Building a shared vision is not a "one-shot" activity. It is ongoing and

never-ending. Importantly, a vision is not truly a "shared vision" until is

connects with the personal visions of people throughout the organization. In other words,

for those in leadership and in positions of power, what is most important is to remember

that their visions are still personal visions. Just because they occupy a position of

leadership does not mean that their personal visions are automatically "the

organization's vision."

Spreading Visions

Leaders do not sell visions. Selling generally means getting someone to do something

that he might not do if they were in full possession of all the facts. Enrolling, by

contrast, literally means "placing one's name on the roll." Enrollment implies

free choice, while "being sold" often does not. Next, committed describes a

state of being not only enrolled but feeling fully responsible for making the vision

happen. The committed people bring an energy, passion, and excitement that cannot be

generated if you are only compliant, that is if you are only playing by the rules.

Managers should remember, there is nothing they can do to get another person to enroll

or commit. Enrollment and commitment require freedom of choice. To establish conditions

most favorable to enrollment managers should:

* Be enrolled themselves.

* Be on the level/honest/ - do not inflate benefits or expectations.

* Let the other person choose.

Anchoring Vision in Governing Ideas

Building a shared vision is actually only one piece of a larger activity: developing

the "governing ideas" for the enterprise, its vision, purpose or mission, and

core values. The vision must be consistent with values that people live by day by day.

The governing ideas answer three critical questions: "What?" "Why?"

and "How?"

* Vision is the "What?" -- the picture of the future we seek to create.

* Purpose (or mission) is the "Why?" -- Why do we exist?

* Core Values answer the question "How do we want to act, consistent with our

mission, along the path toward achieving our vision?"

Limiting Factors

- The visioning process can wither if, as more people get involved, the diversity of views

dissipates focus and generates unmanageable conflicts. Diversity of visions will grow

until it exceeds the organization's capacity to "harmonize" diversity.

Remedy:

The most important skills to circumvent this limit are the "reflection and

inquiry" skills. By inquiring into others' visions, we open the possibility for the

vision to evolve, to become "larger" than our individual visions.

- Visions can also die because people become discouraged by the apparent difficulty in

bringing vision into reality. Here, the limiting factor is the capacity of people in the

organization to "hold" creative tension.

- Emerging visions can also die because people get overwhelmed by the demands of current

reality and lose their focus on vision.

Remedy: In this case, the leverage must

lie in finding ways to focus less time and effort on fighting crises and managing current

reality, or to break off those pursuing the new vision from those responsible for handling

"current reality."

- Finally, a vision can die if people forget their connection to one another. The spirit

of connection is fragile. It is undermined whenever we lose our respect for one another

and for each other's views.

Note, vision becomes a living force only when people

truly believe they can shape their

future. As people in an organization begin to learn how existing policies and actions are

creating their current reality (systems thinking vs. "event mentality"), a new,

more fertile soil for vision develops.

Team learning is the process of aligning and developing the capacity of a team to

create the results its members truly desire.

- The discipline of team learning involves mastering the practices of dialogue and

discussion, the two distinct ways that teams converse.

Dialogue -- in dialogue

there is free and creative exploration of complex and subtle issues, a deep

"listening" to one another and suspending of one's own views.

Discussion -- in discussion different views are presented and defended and there

is a search for the best view to support decisions that must be made at this time.

- Team learning also involves learning how to deal creatively with the powerful forces

opposing productive dialogue and discussion in working teams. Chief among these are

"defensive routines." Teams, for example, may resist seeing important problems

more systematically. Team learning, therefore, requires mastering of systems thinking.

Teams should understand how their own actions may be creating the very problems with which

they try so hard to cope.

- The discipline of team learning requires practice.

Dialogue and Discussion

The principles of dialogue are:

- Suspending assumption. All participants must "suspend" their

assumptions, literally to hold them "as if suspended before us." It means being

aware of our assumptions and holding them up for examination. This cannot be done if we

are defending our opinions. Nor, can it be done if we are unaware of our assumptions, or

unaware that our views are based on assumptions, rather than undeniable fact.

- Seeing each other as colleagues. All participants must regard one another as

colleagues. What is necessary going in is the willingness to consider each other as

colleagues. Colleagueship does not mean that you need to agree or share the same views. On

the contrary, the real power of seeing each other as colleagues comes into play when there

are differences of view. Choosing to view "adversaries" as "colleagues with

different views" has the greatest benefits.

- A facilitator who "holds the context" of dialogue. In the absence of a

skilled facilitator, our habits of thought continually pull us toward discussion and away

from dialogue. The facilitator helps people maintain ownership of the process and the

outcomes -- we are responsible for what is happening; keeps the dialogue moving;

influences the flow of development simply through participating (e.g. "but the

opposite view may also be true").

- Balancing dialogue and discussion. In team learning, discussion is the necessary

counterpart of dialogue. In a discussion, different views are presented and defended, and

this may provide useful analysis of the whole situation. In dialogue, different views are

presented as a means toward discovering a new view. In a discussion, decisions are made.

In a dialogue, complex issues are explored. When a team must reach agreement and decisions

must be taken, some discussion is needed. On the other hand, dialogues are diverging; they

do not seek agreement, but richer grasp of complex issues. Both dialogue and discussion

can lead to new courses of action; but actions are often the focus of discussion, whereas

new actions emerge as a by-product of dialogue.

Conflict and Defensive Routines

The free flow of conflicting ideas is critical for creative thinking, for discovering

new solutions no one individual would have come to on her own. Conflict becomes, in

effect, part of the ongoing dialogue. The difference between great teams and mediocre

teams lies in how they face conflict and deal with the defensiveness that invariably

surrounds conflict. Defensive routines are entrenched habits we use to protect ourselves

from the embarrassment and threat that come with exposing our thinking.

Defensive routines are so diverse and so commonplace, they usually go unnoticed. For

example, in the guise of being helpful, we shelter someone from criticism, but also

shelter ourselves from engaging difficult issues. The most creative defensive routines are

those we cannot see. Some managers believe that to remain confident they must remain

rigid. Whichever bind they find themselves in, managers who take on the burden of having

to know the answers become highly skillful in defensive routines that preserve their aura

as capable decision makers by not revealing the thinking behind their decisions. The

paradox is that when defensive routines succeed in preventing immediate pain they also

prevent us from learning how to reduce what causes the pain in the first place.

How to make defensive routines discussible is a real challenge. One has to have the

skills to confront defensiveness without producing more defensiveness. The core principle

here is a ruthless commitment to seeing rather than obscuring current reality.

Practice

- have all members of the team together;

- explaining the ground rules of dialogue:

- suspension of assumptions

- acting as colleagues; no hierarchy

- spirit of inquiry (explore the thinking behind views and the evidence used that leads to

these views)

- enforce those ground rules;

- encourage team members to raise the most difficult, subtle, and conflictual issues

essential to the team's work. Acknowledge your own frustration, fears, insecurity,

assumptions and reasoning. Invite criticism.

|