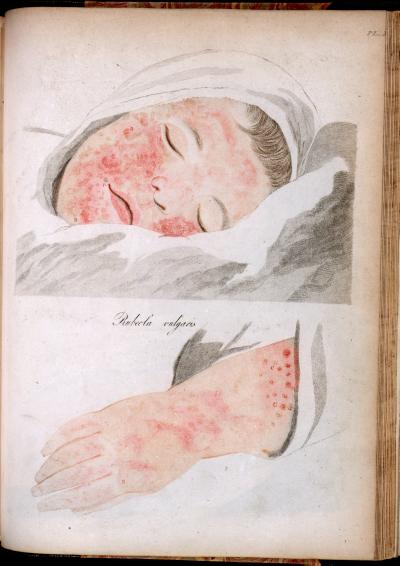

Measles

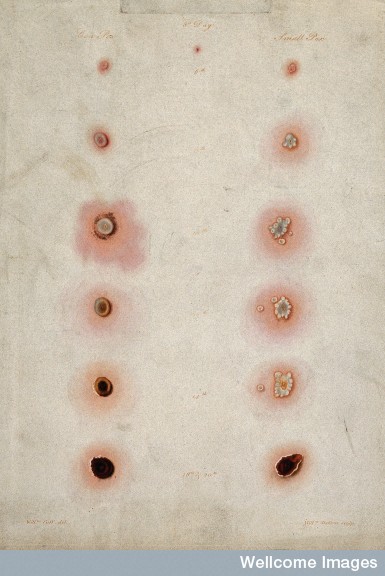

Engraving taken from Robert Willan's (1757-1812) On Cutaneous Diseases, (London: J.Johnson, 1808). Courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.

Early Modern Illnesses and Treatments

Surgeries, Deformities and Disease

Smallpox and Measles

by Emily Dymock

|

Measles |

Smallpox and measles were highly contagious diseases that decimated Europe from ancient times to the modern era, killing more people than all the world's wars combined.

In 1967 smallpox was targeted for eradication by the World Health Organisation, and was officially certified as eradicated in 1980. Smallpox was first recorded in Europe sometime between 160-180 AD, likely brought from the east by Roman legions and it was known as the Plague of Antonius, named after the ruling roman emperor Marcus Arelius Antonius.(1) Several populations, such native tribes throughout the Americas that had never encountered smallpox before it was brought to their shores by Europeans during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and they were decimated as they had no natural resistance or immunity, which was transmitted through contact with the disease. During the early seventeenth century, the physician Isbrand de Diemerbroeck observed that people who survived a bout with smallpox would not be susceptible to it even if they were exposed to the illness a second time. He concluded that full immunity was the result of surviving the disease; however, if there was a smallpox epidemic, all the citizens who had previously been exposed to the virus had a natural resistance to the disease through their previous contact.(2) Therefore the members of the population to be most susceptible to the disease were children who had not yet lived through a smallpox outbreak, and it killed one in every three children who were exposed…

In 1655, four of Queen Elizabeth’s physicians conveyed the common belief that susceptibility of children to many diseases, especially smallpox and the measles, was transmitted by the menstrual blood of pregnant women. If the mother was exposed to an unnaturally high body temperature, either through a fever, weather conditions, or excessive physical labour, the mother’s blood became corrupted. This corrupt blood mixed with that of the unborn child in the womb, leaving the child vulnerable to smallpox and measles.

“An unnatural heat is increased in all the body, causing an ebullition of the blood, by the which this filthy menstrual matter is separated from our natural blood and the nature being offended and overwhelmed therewith, doth thrust it to the outward pores of the skin as the excrements of blood which matter if it be hot and slimie then it produceth the pox, but if it be dry and subtil, then it produces the measles.”(3)

Isbrand Diemerbroeck, a teaching physician from Utrecht University, one of the oldest universities in the Republic of the Seven United Provinces (now the Netherlands), and the author of an extended medical treatise on smallpox and the measles, agreed that a child’s vulnerability to the disease was formed in the uterus. His theories explained why, in his opinion, men were more likely to contract the diseases because women sloughed out the corrupt maternal blood every month, while it only continued to fester inside a man.(4) The early modern view of menstrual blood was both positive and negative when it concerned a child’s susceptibility to contract smallpox and measles. Menstrual blood was argued to give women an advantage in terms of health and gave them a stronger resistance to diseases as they could purge themselves of corruptions found in their blood. However, because those corruptions were formed in the uterus, children, especially boys, were argued to have had a much higher risk of contracting these deadly diseases.

|

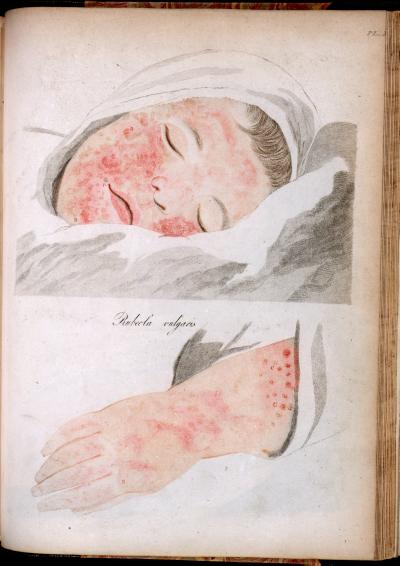

An Arm with Three Smallpox Pustules |

Early modern medical practitioners considered other external causes that could lead to either smallpox or measles. An early modern physician and apothecary Nicholas Culpeper argued that the most prominent external cause was an impurity present in the air, which could aggravate or ignite an already existing corruption in the blood.(5) The second external cause was related to the balance of blood and humours within the sick person’s body which would be effected by not enough exercise, too frequent bathing, excessive anger or fear, or by over eating. A third, according to Diemerbroeck was contagion, which he argued constantly flowed out of the bodies of the sick, and could poison anyone who came into contact with it.(6) All of the medical treatises recommended that anyone- not only children- who had never been afflicted with smallpox should avoid contact with the sick or those who treated them.

The first symptom to arise for both smallpox and measles, as observed by many early modern physicians, was a fever. According to John Pechey (of the college of Physicians in London, 1697) the fever that accompanied the measles could be so mild that it could go unnoticed. Although smallpox also began with a fever, it was typically much hotter and was accompanied by convulsions, intense back pain, a running nose, rapid heart rate, and difficulty breathing.(7) The spots would first appear on the face and then spread to the hands, feet and chest. Pustules could also appear on the inside of the throat, ears, nose, beneath the eyelids, and on the internal organs which could cause internal bleeding. The welts in the throat could also suffocate the victim, which is why the disease was much more dangerous than measles. Early modern authors described smallpox welts that rose to form white caped wells in the skin which were filled with the putrefying humours that the body was attempting to dispel. Medical practitioners argued that the faster that these white caps formed and the fever broke, the better the prognostic was for the suffering person. If the welts did not arise quickly, or if they sank back into the flesh after surfacing, early modern practitioners inferred that the putrid humours were inflaming the internal reaches of the body, leading to an extended fever and possible death or else to a lifetime of disability. However, the early modern medical images do not convey the horror, and severity of the disease. Each image isolated smallpox into close up images showing only one or two pustules, which separates the physical effects of the disease from the suffering of the child. The only way to comprehend the severity of the disease is to compare the early modern images with photographs from the early twentieth century which show the full effects of the disease. This provides a well rounded understanding of the physicality of the disease, by combining a detailed view of the individual pustules with an image that shows the symptoms over a child’s entire body.

|

Gloucester Smallpox Epidemic, 1896 |

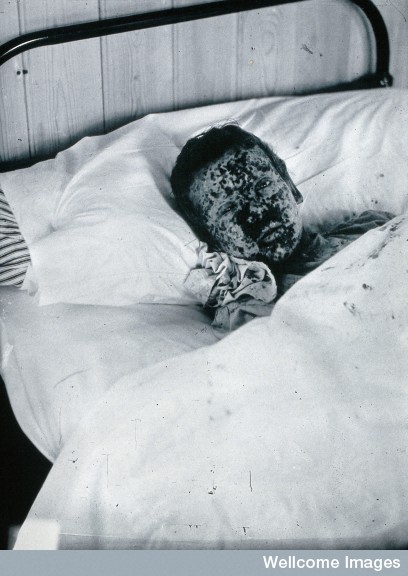

Ambroise Paré a famous French physician and surgeon from the sixteenth century, argued that smallpox and measles could not be distinguished from one another until the third or fourth day after the spots began to show upon the skin. When a child was stricken with smallpox, the spots would fill with putrid cream coloured liquid by the third or fourth day, creating white caped pox marks which would eventually scab and fall away. The spots created by the measles however remained flat and red throughout the illness. Paré argues that

"The smallpox arises of a more grosse and viscous matter, to wit, of phlegmatic humour. But the measles of a more subtle and hot, that is a choleric matter, therefore this yields no marks thereof, but certain small spots without any tumour, and these either red, purple or black. But the smallpox are extuberating pustules, white in the middles, but red in the circumference, an argument of blood mixed with choler. “(8)

The French surgeon also distinguished the two diseases based on the severity of the corrupting matter which caused each illness. He argued that when compared, measles’ temperament was subtle and less biting than the matter which caused smallpox. Paré’s key distinction between the measles and smallpox was that the corruption which caused the measles did not remain trapped under the skin of the sick, which was how he explained that the spots caused by the measles were not as itchy or painful as those formed by the smallpox.(9)

In their treatises, medical authors typically outlined various treatments after providing extensive descriptions of the diverse symptoms that could indicate the presence of either smallpox or measles. During the fever both Queen Elizabeth’s physicians and Ambrose Paré recommended the best treatment was to keep the sick separated from the rest of the household, covered in warm, preferably red blankets and allowed to sweat out the fever. The colour red was considered to be both therapeutic and harmful for its ability to provoke further inflammation in the sick. Ambrose Parey contested that those people who were ill with pox under their eyelids should be kept from looking upon the colour as he argued it would increase the heat and the swelling under the eyelids, which could quickly lead to blindness.(10) However, red was argued to also have therapeutic effects, as red blankets were recorded as provoking the pox to emerge through sympathetic response: the red pox was attracted to a red blanket which helped to draw the corrupted humours to the surface of the skin to quicken the progression and recovery from the disease. Red blankets were observed and recorded by many practitioners to provoke the disease much faster than any other colour of blanket. However, in early modern Europe, blankets were dyed specific colours as an indicator of their thickness, and red indicated the thickest weave of blanket, which made them the most effective in warming patients with a fever.(11)

|

| Roseaola, caused by vaccine and by smallpox. Engraving taken from On Cutaneous Diseases, by Robert Willan, (London, J.Johnson, 1808.)Courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto |

Michael Underwood recommended using phlebotomy (or bleedings) as another way to help alleviate the heat of a fever, both before and after the fever had broken, as long as the child was old enough to bear the procedure (usually after the child had their first set of teeth).(12) However, Underwood, Pechey and Diemerbroeck urged caution when treating children taking into account their age, health and temperament. Bleeding was widely understood to cure the diarrhoea (looseness of the bowels) which was one of the most deadly side effects that accompanied both smallpox and measles. Bleeding cured this looseness because, in keeping with early modern humoural medicine, it prevented the inflamed and corrupted blood from rushing to the bowels of the sick person, a situation that could be deadly.(13) Queen Elizabeth’s physicians recommended bleeding from the arm if the pox had not yet been raised to the skin, but only if the sick person was more than fourteen years of age. If they were younger, then the treatment might do more harm than good, as young children were already considered to be too weak to withstand bleedings, and after further corruption caused by illness, they would almost certainly die. Queen Elizabeth’s royal physicians advised that the best way to drain the blood from younger children was by using blood suckers (ie leeches) rather than through cutting one or more the veins.(14)

Engraving taken from On Cutaneous Diseases, by Robert Willan, (London, J.Johnson, 1808.)Courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto After the fever had abated and the only traces of the disease that remained were the welts upon the skin, many rich individuals would request the operation of the golden needle, which was used to break and drain the pustules in an attempt to speed along the healing process and reduce scarring. Ambrose Paré recommended this treatment as a way to release the putrid liquid trapped in the pustules which he argued ate away at the healthy skin underneath, ultimately causing the severe scarring associated with smallpox.(15) Queen Elizabeth’s physicians explained the treatment:

“With a golden pinne, or needle, or for lack thereof a copper pinne with serve, do you open every pustule in the top, and so thrust out the matter therein very softly and gently with a soft linnen cloth, and if you perceive, the places do fill againe, then open them againe as you did first, for if you do suffer the matter which is in them to remain over long, then will it fret and corrode the flesh, which is the cause of those pits which remaineafter the Pox are gone.”(16)

|

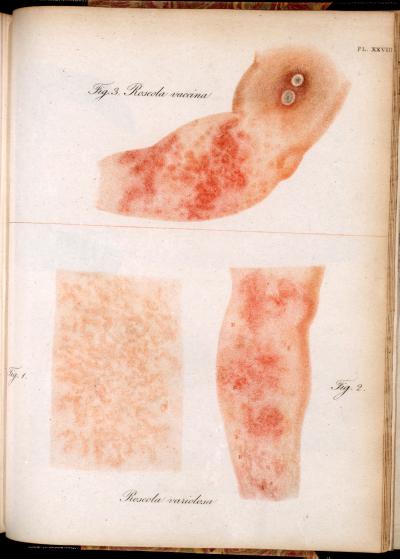

| A Comparison between Vaccinated (Cowpox) and Smallpox pustules from the 3rd to 20th day of the disease.

Etching by W. Skelton, taken from A Bio-bibliography of Edward Jenner, 1749-1823. (London 1951)by William Cuff. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library. |

Letting the disease run its course was the only cure known for the either disease, as all the treatments recommended by early modern physicians were meant to manage the symptoms and speed along the progress of the illness. Diemerbroeck provided the details of many remedies designed to strengthen the internal organs, to aid with a suffering child’s breathing, and to speed up the progression of the fever, but concluded that time was the only true cure. Diemerbroeck admitted that many parents (especially wealthy ones) did not like to hire a physician who would do little for their sick child. So the ever practical Diemerbroeck included in his book a remedy that would alleviate the parents’ worries without affecting the child’s health:

“Prescribe a small quantity of bezoars stone, with magistry pearls or crabs eyes or essence of corral, adding thereto some few grains of saffron, or some suck thing that won’t disturb nature in her work.”(18)

|

Vaccination: "Dr. Jenner Performing his first vaccination, 1796" Oil painting by Ernest Board. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library. |

|

| Last smallpox victim Rahima Banu, 1975, Courtesy of the Wellcome Library |

The most effective step in the prevention of smallpox was in the invention of the vaccination by Englishman Edward Jenner in the late eighteenth century, and it was the first widely used vaccine in medical history. In 1798 Edward Jenner published an account of Europe’s first successful vaccination, which was highly effective in the prevention of even the most sever cases of smallpox in those who had been treated. His technique involved injecting a small amount of cow pox -a strain of smallpox found only in cows- which caused small pustules on the human skin which came into contact with the infection. The difference between cow pox and smallpox is exemplified in the adjacent image, where the smallpox, on the right, forms many more pustules and does not form a scab until much later in the development. Jenner’s trial involved injecting cow pox material taken from the hand of a young mild maid, Sarah Nelmes, who had cowpox pustules through contact with an infected cow, and injecting it into his test subject James Phipps, the eight year old son of Jenner’s gardener, as shown in the painting on the right. Phipps was purposefully exposed to small pox six weeks later, and did not demonstrate any symptoms of the disease. Jenner claimed that the vaccine provided protection for an entire lifetime, but it was highly criticised by the public as it was eventually proven that Jenner’s vaccine only provided protection for a maximum of ten years. In 1840 the Vaccination Act passed in Britain provided free vaccinations for all children in an attempt to control the continuing smallpox epidemic. This act also made inoculations, which had more potential to spread the disease than to prevent it, illegal.

In 1967, smallpox was targeted for eradication by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Smallpox was a prime candidate for eradication because it was exclusively spread by human contact, had a short incubation period and had no natural animal host; it was theorised to be possible to eradicate the disease entirely. With a targeted response teams formed by WHO, whose soul purpose was to monitor any outbreaks, and were charged with installing strict quarantines zones and mandatory vaccinations of the towns and surrounding areas where the disease had been reported. The last natural case of the more severe strain of smallpox, variola major was in Bangladesh, in two year old Rahima Banu in 1975 (image on the left), and the last case of variola minor, which occurred in 1977 was found in Somalian Ali Maow Maalin. By 1980, smallpox had been classified as officially eradicated by WHO, marking one of the biggest victories over disease that humanity has ever realized.(22)

Notes:

1)Donald R Hopkins. Princes and Peasants: Smallpox in History. (The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1983) p22.

2)Isbrand de Diemerbroeck. Trans. William Salmon. The Anatomy of Human Bodies; Comprehending the most Modern Discoveries and Curiosities in that Art, to which is added A Particular Treatise of the Small-Pox and Measles Together with several Practical Observations and Experienced Cures. (London, Printed for W. Whitwood, 1694) p2.

3)M.A. Queen Elizabeth’s Closset of Physical Secrets. (London: Will Sheares, 1656) p51-52.

4)Isbrand de Diemerbroeck. Trans. William Salmon. The Anatomy of Human Bodies; Comprehending the most Modern Discoveries and Curiosities in that Art, to which is added A Particular Treatise of the Small-Pox and Measles Together with several Practical Observations and Experienced Cures. (London, Printed for W. Whitwood, 1694) p5.

5)Nicholas Culpeper. Culpeper’s Directory for Midwives or A Guide for Women. (Lodon: Printed by Peter and Edward Cole, 1662) p234.

6)Isbrand de Diemerbroeck. Trans. William Salmon. The Anatomy of Human Bodies; Comprehending the most Modern Discoveries and Curiosities in that Art, to which is added A Particular Treatise of the Small-Pox and Measles Together with several Practical Observations and Experienced Cures. (London, Printed for W. Whitwood, 1694) p6

7) John Pechey. A General Treatise of the Disease of Infants and Children. (London: Printed for R. Wellington, 1697) p27.

8)Ambroise Parey, trans. Th. Johnson. The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey. (London, Th. Cotes and R.Young Anns, 1634) p757-758.

9) Ibid, 758.

10)Ibid, 760.

11)Isbrand de Diemerbroeck. Trans. William Salmon. The Anatomy of Human Bodies; Comprehending the most Modern Discoveries and Curiosities in that Art, to which is added A Particular Treatise of the Small-Pox and Measles Together with several Practical Observations and Experienced Cures. (London, Printed for W. Whitwood, 1694) p14-15.

12)Isbrand de Diemerbroeck. Trans. William Salmon. The Anatomy of Human Bodies; Comprehending the most Modern Discoveries and Curiosities in that Art, to which is added A Particular Treatise of the Small-Pox and Measles Together with several Practical Observations and Experienced Cures. (London, Printed for W. Whitwood, 1694) p115.

13) John Pechey. A General Treatise of the Disease of Infants and Children. (London: Printed for R. Wellington, 1697) p 46.

14) M.A. Queen Elizabeth’s Closset of Physical Secrets. (London: Will Sheares, 1656) p 56.

15)Ambroise Parey, trans. Th. Johnson. The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey. (London, Th. Cotesand R.Young Anns, 1634) p 760.

16)M.A. Queen Elizabeth’s Closset of Physical Secrets. (London: Will Sheares, 1656) p59.

17) John Pechey. A General Treatise of the Disease of Infants and Children. (London: Printed for R. Wellington, 1697) p37.

18)Isbrand de Diemerbroeck. Trans. William Salmon. The Anatomy of Human Bodies; Comprehending the most Modern Discoveries and Curiosities in that Art, to which is added A Particular Treatise of the Small-Pox and Measles Together with several Practical Observations and Experienced Cures. (London, Printed for W. Whitwood, 1694) p14.

19)Donald R Hopkins. Princes and Peasants: Smallpox in History. (The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1983) p17.

20)Michael Underwood, A treatise on the Diseases of children with directions for the management of Infants from the Birth. (London: J Mathews, 1784) p116-117.

21) Ibid, 117.

22) Derrick Baxby, ”The End of Smallpox” History Today. March 1999, v 49, i3, p14.