Peter Paul Rubens,1625. Musee de Louvre, Paris, France

Early Modern Illnesses and Treatments

Surgeries, Deformities and Disease

|

| Anne of Austria, Queen of France. Peter Paul Rubens,1625. Musee de Louvre, Paris, France |

Cancer of the Breast In the

Seventeenth Century:

Anne of Austria, Queen of France (1601-1666)

by Sara Kowalski

In 1664, after finally consulting physicians about a lump she had first discovered in her breast the previous year, Anne of Austria, queen mother of King Louis XIV of France (fig. 1), remarked “that having seen cancers in the nuns of Val-de-Grâce, who had died all rotten, she had always had a horror of this disease, so terrible to her imagination.”(1)

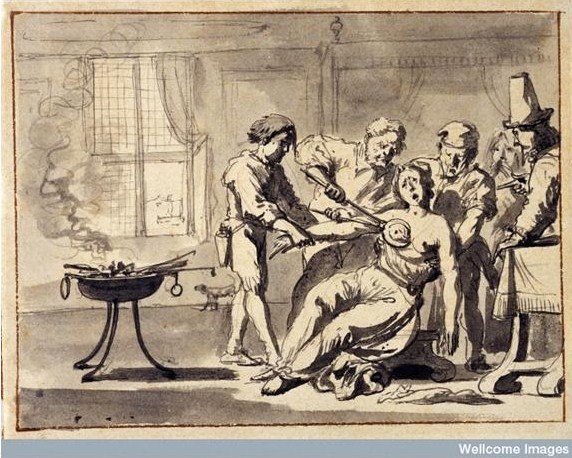

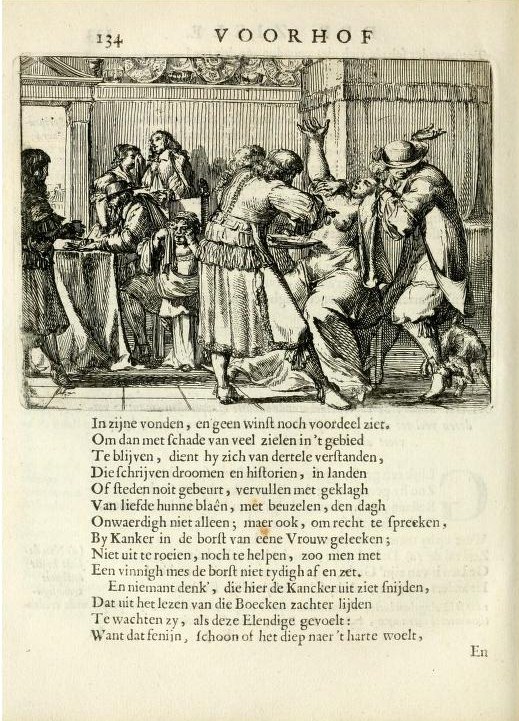

Fear of developing breast cancer was notuncommon among Western women in the early modern period. Cancer, especially of the breast, was generally regarded as incurable, and those methods employed in hope of a cure, or at least to relieve pain and prolong life, were often gruesome and dreadful. Johannes Scultetus’ (1595-1645) seventeenth-century medical illustration of an amputation of the breast (fig. 2) is a good example of the surgical procedures for breast cancer in general use at the time, which from a modern point of view appears almost barbaric. Two other seventeenth-century drawings illustrate mastectomies as they are being performed on suffering women. In one image, a surgeon excises a woman’s breast with a large surgical instrument that resembles an oversize cigar cutter, while a smouldering set of cautery irons stands on the left waiting to be applied to the wound (fig. 3). Held down by two men, the woman appears to be fainting as a look of agony washes over her face. Performed without anaesthetics, this kind of surgery would have been almost unbearable and exemplifies the pain endured by women who underwent operative treatment for cancer of the breast. Another image by the Dutch painter and illustrator Romeyn de Hooghe (1645-1708) vividly portrays a mastectomy performed on a client in her own bedroom (fig. 4). The gripping scene similarly depicts the woman seated, held down by an assistant as a surgeon actively excises her diseased breast, her family members huddling in the background, weeping. While surgery to remove cancerous tissue from the breast was uncommon in the seventeenth century, the prospect of surgery and disfigurement nevertheless generated fear. Surgery aside, the embarrassment and sense of shame that accompanied the disease, which was regarded as dirty and of low social value, and the uncertainty that arose with a breast cancer diagnosis were reason enough for women to dread the disease.

|

Amputation of the breast |

Having witnessed nuns dying of breast cancer in the infirmary on her visits to Val-de-Grâce, Anne was no stranger to the physical disfigurement and pain brought on by the disease. The sight of rotting tissue and foul odour of one nun’s advanced tumour, which had destroyed the side of her torso, opening up her body to view, deeply affected the queen-mother, who expressed intense dread at the prospect of ever being similarly afflicted.(2) It thus comes as no surprise that when she first discovered a small lump in her left breast in 1663, she delayed consulting a physician and kept her discovery a secret, quietly enduring the pain and confiding only in her close friend Madame de Motteville, whose notes and memoirs offer a rare view into the Queen’s affliction with cancer and firm resolution to endure suffering.

When Anne finally sought medical attention in November 1664, she was immediately at the mercy of physicians who held competing views as to how the advanced tumour should be treated. Even those who had never examined her breast debated her condition and treatment options, which were all but decisive. When the doctors at court concluded that she had cancer and pronounced it incurable, various remedies and treatments were nevertheless tried on her body. Prescribed treatment was either conservative, consisting of bleeding, purging, a regimented diet, and topical medicines, or surgical.(3) Her primary physician, Pierre Séguin (1566-1623), and the personal physician of the King, Antoine Vallot (1594-1671), whom Séguin consulted almost immediately, both subscribed to the conservative attitudes towards cancer of the Paris faculty of medicine, which adhered to the Greek physician Galen’s (c. 130-200 CE) humoural theory. In this view, diseases were understood in terms of the four bodily fluids, or humours: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. Cancer, according to Galen, was caused by an excess of black bile that accumulated most often in the breasts of women. While physicians might have occasionally identified or speculated about internal malignancies, external cancers, and especially those of the breast, were most visible and were thus thought to be the most common. Still, cancer was a general term applied to painful unnatural growths that, having the appearance of crab-like veins, might or might not be ulcerated, but typically spread, eventually causing death. Because cancer was understood as a systemic disease, Galen’s prescribed treatment consisted of bleeding, purgation, and a dietary regime in attempt to restore a healthy balance of fluids in the diseased body. Occasionally breast cancer was treated with surgery, whether by simple excision or in the form of mastectomy, but only if the tumour was readily accessible and not too deeply-seated. Operative approaches were widely debated and performed with great risk.(4)

|

Excision of the Breast |

Thus, the first treatment Anne received was a non-operative regimen of bleedings and purgings, combined with the regular application of a hemlock ointment to her breast to relieve pain.(5) When the bleeding failed to improve her condition, alternate remedies were sought out and tested, which mostly consisted of ointments or caustics applied to the affected breast, in hope that they might eradicate the tumour. Father Gendron, a village priest from Orléans with no formal medical training, boasted a “secret remedy” of belladonna and burnt lime that would harden the diseased breast and allegedly cure the cancer. The paste was tried on Anne, but by August 1665 when it brought no improvement and her condition worsened—her primary tumour ulcerated, she developed abscesses and additional tumours, and regularly suffered from fevers—she resolved to accept a proposal for treatment offered by Pierre Alliot, a physician from Lorraine, although “she felt he was destined not to cure her, but to be her executioner.”(6) His controversial treatment, which Motteville describes as violent and extremely painful, consisted of an arsenic paste that, applied to the tumour, mortified the diseased tissue, which he would then cut away with a razor.(7) From August 1665 until January 1666, Anne underwent Alliot’s daily operations and surgical removal of decaying tumour tissue, which at least temporarily seemed to provide some relief and apparent progress against the disease. When fever and other complications persisted, however, early in January 1666 she agreed to replace Alliot’s therapy with treatment from a doctor from Milan who promised an effective remedy of secret composition. According to Motteville, his remedies “had no other effect than to hasten her death,” consuming the flesh of her cancer too quickly and not allowing her body to recover.(8) Whether the treatment was itself unsuccessful or was simply performed in vain, the disease progressed quickly, resulting in Anne’s death on January 20, 1666

|

| Mastectomy Engraved by Romeyn de Hooghe, taken from F. Van Hoogstraten, Voorhof der ziele, Rotterdam, 1668. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library. |

Despite the various attempts at treating Anne’s diseased breast, the cancer continued to progress, spreading to her arms, shoulders, and neck, both disfiguring and weakening her body and causing her prolonged agony. At first, Anne found it particularly humiliating to be dying of breast cancer. For a refined woman who enjoyed sensuous pleasure, bathed regularly, wore only the finest fabrics and most exquisite perfumes, and commanded wealth and attention, cancer made her feel dirty and worthless. The pleasure that she had taken in her body throughout her life quickly degenerated, and as her tumours ulcerated, they discharged black fluids and wretched odours, a suffering that was “repugnant to her nature”(9) and which her servants attempted to subdue by covering her nose with heavily perfumed handkerchiefs.(10) Reflecting on her condition, Motteville recounts that “[Anne] often said she never could have believed that a fate so different from that of other human beings could be hers; that usually no one rotted till after death, but as for her, God had condemned her to rot in life.”(11) Still, she showed no weakness or self-pity. As her disease progressed and she approached death, Anne found purpose to her suffering. “God wills to punish me in this way,” she confided in Motteville, “for having had too much vanity and for loving the beauty of my body too well.”(12) Believing that God had given her an opportunity for penance for her sins and self-indulgences, Anne accepted her affliction, piously tolerated her incessant pain, and understood herself as a living reminder to others of the transience of worldly pleasures and vanities. In the final days before her death, she restated simply, “I have abandoned my body to the justice of God; men may do what they like with it,” and finally, “I felt that it must be.”(13)

For Anne, and presumably for other women dying of breast cancer in the early modern period with little hope of an effective cure, the greatest comfort was to find spiritual meaning in bodily suffering. Anne’s steadfast suffering, however, was uniquely regarded as symbolic and even saintly. Putting her illness in the service of her eternal salvation, she became a religious example of humility and piety for others to observe. In Motteville’s commemorative words: “The sincere sense she had of her nothingness gave her grandeur, and her repentance for the regard she had felt in her youth for the beauty of her body was the cause of the saintliness of her death.”(14)

Notes:

1)Madame de Motteville, Memoires of Madame de Motteville on Anne of Austria and her Court, vol.3, trans. Katharine Prescott Wormeley (Boston: Hardy, Pratt & Company, 1902),310. Descriptions of Anne’s disease and her reactions to it are available because of the detailed notes and memoires of Madame de Motteville, a close friend who spent some twenty-five years of her life at or near court and made particular efforts at recording her encounters and conversations with Anne.

2)Ruth Kleinman, “Facing Cancer in the Seventeenth Century: The Last Illness of Anne of Austria, 1664-66,” Advances in Thanatology 4 (1977): 40.

3)Daniel de Moulin, A Short History of Breast Cancer (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1989), 24.

4)Kleinman, 41-42 and Moulin, 6-9, 24-26.

5) Kleinman, 42.

6)Motteville, 324.

7)Motteville, 334.

8)Motteville, 344-47.

9)Motteville, 345.

10)James S. Olson, Bathsheba’s Breast: Women, Cancer & History (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 25.

11)Motteville, 334-35.

12) Motteville, 345

13)Motteville, 347 and 351

14)Motteville, 314.