Background and Rationale

Although suburban development and fragmentation are recognized as major threats to biodiversity today1, coyotes (Canis latrans)

have integrated themselves into a human-dominated landscape and are now

considered the top terrestrial predator in many ecosystems2.

There are both positive and negative outcomes associated with coyote

inhabitation of urban areas. Coyotes have economic value as furbearers,

social value as watchable wildlife and ecological value associated with

biodiversity maintenance. As a generalized predator, coyotes limit

smaller, more specialized carnivores, such as foxes and cats, allowing

small mammals and ground-nesting birds to increase3.

Coyotes, however, can conflict with humans as a result of altercations

with pets, perceived risks to small children, and their potential to

act as disease vectors4. Urban wildlife managers strive to maintain diversity in urban parks and natural areas and resolve human-wildlife conflicts5,

attempting to strike a balance between ecosystem integrity and

biodiversity and the social carrying capacity for wildlife species.

As

coyote-human conflicts emerge in the City of Edmonton and surrounding

areas, key knowledge gaps have appeared. Coyotes exist along an

urban-non-urban gradient, where the activity levels of humans vary. To

develop an effective coyote management plan, managers must have a

better idea of how coyote activity patterns differ along this gradient.

This study’s main objective is to assess coyote circadian (daily)

activity patterns in relation to human activity levels and to determine

if coyote relative activity varies across site types.

A better understanding of

coyote circadian activity patterns may help minimize conflict with

humans. Coyotes in natural, undisturbed areas are most active during

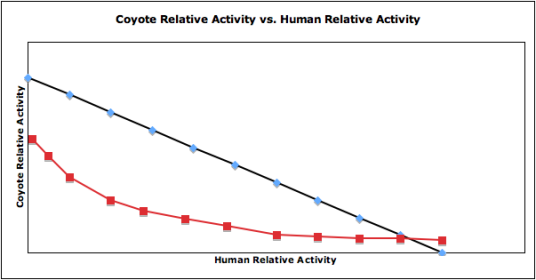

the day6,7 as supported by evidence that coyote vision is best adapted to diurnal and crepuscular activity9. Coyotes in human- dominated areas, however, are mostly nocturnal4,7,8 and show low activity levels in areas of higher human activity9(Figure 1). The existence of direct exploitation also results in shifted activity patterns7,8, while unexploited coyote populations have demonstrated high levels of diurnal activity3.

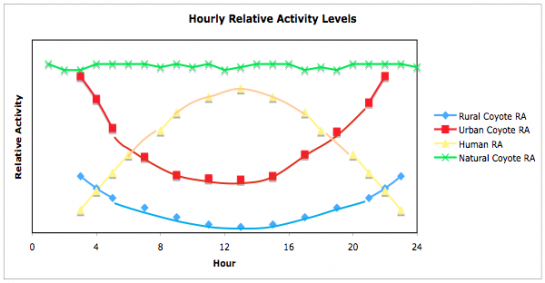

Both urban and non-urban coyotes are expected to be largely nocturnal

and crepuscular, however urban coyotes may show higher levels of

daytime activity owing to the absence of direct exploitation within the

city (Figure 2). If urban coyotes are more active during the

day, it may be important to incorporate this information into

management and education plans.

Figure 1. Theoretical coyote relative activity levels in response to human relative activity levels. The expected decline in coyote activity as a result of increased human activity may be linear or logarithmic.

Figure 2. Theoretical coyote relative activity levels in urban, rural and natural sites in comparison to human relative activity levels.

Literature

1 Markovchick-Nicholls et al. 2008, Con. Bio. 22(1):99-109; 2 Gompper 2002, BioScience 52(2):185-190;3 Crooks and Soulé 1999, Nature 400:563-566; 4 Grinder and Krausman 2001, J. Wildl. Manage 65(4):887-898; 5 Westworth 2006, Coyotes Still Sing in My Valley, ed.Wein:87-104.6 Gese et al. 1996, Can. J. Zool 74:769-783; 7 Kitchen et al. 2000, Can. J. Zool 78:853-857; 8 Kavanau and Ramos 1975, Am. Nat. 109:391-418; 9 George and Crooks 2006, Bio. Con. 133:107-117