http://www.ualberta.ca/folio

| ||

| Volume 36 Number 13 | Edmonton, Canada | March 12, 1999 |

|

http://www.ualberta.ca/folio | ||

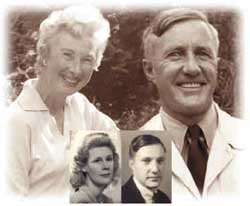

Gladys (Marion) May Young and her husband Dr. Roland Young, bequeathing $3.5 million to the U of A in scholarship funds |

On a quiet, nondescript morning last August, development officer Brian Shea received a phone call that made his jaw drop.

"Can you repeat that number please?" he asked the Victoria, B.C. trust officer no less than three times. To his considerable surprise, one Gladys May Young had died, leaving the University of Alberta a staggering $3.5 million for undergraduate student scholarships. There were no further restrictions attached to the bequest, only that the money help students who need it.

It was like manna from heaven. And according to Ron Chilibeck, director of Student Awards, it's the largest private gift for undergraduate scholarships in the university's history.

What made the bequest all the more intriguing was no one here had ever heard of Gladys Young, who died last July at the age of 89. University databases turned up nothing. After a little more digging, however, Shea discovered she was the wife of Portage La Prairie native and U of A alumnus Dr. Roland Young (B.Sc. 1928, M.Sc. 1930), considered at one time the world's leading expert on the chemical properties of cobalt. Although Young never returned to Alberta after graduating from the U of A, it was his dying wish in 1988 that the bulk of his estate support future generations at his alma mater. Gladys Young (who preferred to be called Marion) honored that request.

From her home in East Sussex, England, Susan Slade, Marion's niece, said despite being ignored in her aunt's will because of a falling out between her mother and Marion in the '60s, she was nonetheless "delighted" to hear about the gift. "I know that's what my uncle would have wanted," she said.

After receiving his doctorate from Cornell University in 1934, Young worked for a time at the Inco Mines in Sudbury, Ont., then moved to Africa where he served as a head chemist in the copper belt of what is now northern Zimbabwe. Soon after, he moved to Johannesburg, South Africa to take up a post as head of the Diamond Research Laboratory.

Marion, meanwhile, had grown up in England, the daughter of a sergeant major in the British cavalry. While she lacked the benefits of station and higher education, serving an apprenticeship as a dressmaker in her teens, she nonetheless became "an English gentlewoman and a classy lady," said Marion's lawyer and friend, Laurence Johnson.

Marion was a stunningly beautiful woman and a well-known poster girl in England in the '30s, according to Johnson. By the late '40s she was in the process of divorcing her second husband (the first died years before of typhoid fever after eating bad oysters), when a friend invited her to start a new life in South Africa. She accepted and was soon introduced to Young, no doubt one of the most eligible bachelors in Johannesburg.

"My uncle had never been seriously involved with a lady before," said Slade. "I think he just got bowled over by her."

After a whirlwind romance, the two were married in 1949, but not before Young picked out a 2.5 carat blue diamond for Marion from the finest stones De Beers had to offer. The two were steadfastly devoted to each other for the remainder of their 39-year marriage.

The Youngs returned to Canada in the early '50s and the childless couple moved to Victoria where Young worked for the B.C. government's Ministry of Energy and Mines. In 1972, the Youngs spent a year in Amman, Jordan, where Roland worked for the UN as a resident consultant helping to set up the first chemical analysis facility for the government. When he returned to Canada, he spent the rest of his career writing and consulting on chemical issues.

"He was Mr. Cobalt," said Johnson. "If you wanted to know about it, he was the man to call. Everything from medicinal purposes to using it for a dye agent - all the properties."

After Roland died in 1988, aged 82, Marion became a recluse, afraid people would only take an interest in her for her money, says Deanna Chee, who helped care for Marion in the final days of her life. But for those who knew her, "she was an absolutely beautiful, striking woman, and a very sweet, dear lady," says Chee. "She struck a chord in my heart."

Folio front page |

Office of Public Affairs |

University of Alberta |