Eʋe language and orthography

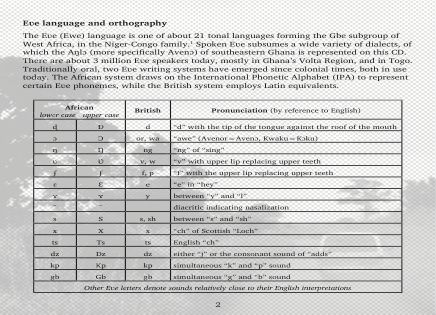

The Eʋe (Ewe) language is one of about 21 tonal languages forming the Gbe subgroup of West Africa, in the Niger-Congo family. Spoken Eʋe subsumes a wide variety of dialects, of which the Aŋlɔ (more specifically Avenɔ) of southeastern Ghana is represented on this CD. There are about 3 million Eʋe speakers today, mostly in Ghana’s Volta Region, and in Togo. Traditionally oral, two Eʋe writing systems have emerged since colonial times, both in use today. The African system draws on the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to represent certain Eʋe phonemes, while the British system employs Latin equivalents.

The Character of Eʋe Performance

When I first arrived in Ghana I had already been playing the traditional acoustic music of the Eʋe people for several years, through study and performance in Boston with ethnomusicologist David Locke

and Ghanaian master musician Godwin Agbeli. Yet I was scarcely prepared for my first Eʋe community performance, a powerfully collective, seamless multiart; a magnificent mosaic of socially interactive singing, dancing, and percussion; an intergenerational, polyphonic symphony of sociomusical conversations, in which everyone — male and female, young and old — plays a part.

The genius of Eʋe performance lies in its ability to engage every participant by enabling personal variation on endlessly repeated, collectively-held aesthetic forms, socially interlocked via call-response complementarity. Such performance generates solidarity through individual expression linked in sociomusical interaction, amplified by full community participation and multiple feedback loops operating through a massively parallel tangle of redundant multimedia channels, weaving a densely connected, affectively- charged social network.

In Eʋe villages, such performances, punctuating the quotidian with spectacular bursts of sights and sounds, are tied to rhythms and cycles of life, society, nature, and supernature:3 agricultural and hunting festivals; shrine rituals; political, military, and historical ceremonies; outdoorings of children, and — most common of all — funerals.

On the surface, performance appears individually expressive, variable, sometimes chaotic. Yet, performance radiates from a compact core of recurring patterns. Beneath its manifold surface, performance is highly ordered; its compositional elements (dance, percussion, and song) are integrated, progressing in a balanced aesthetic arc. This is the paradox of Eʋe performance: diversity within unity, order within chaos, individualism emerging from formal constraints.

Fieldwork

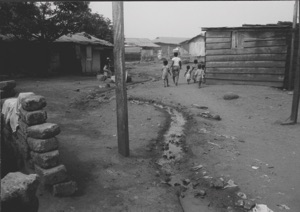

From September 1988 until January 1989 I lived in Ghana, participating in Eʋe life from my base in Ashaiman, a squalid, bustling, lively, multi-ethnic workers’ community about twenty miles east of Accra, adjoining the deep-water port city of Tema — and brimming with community music from every corner of Ghana.

Monthly Lebene performances were preceded by several nights of singing rehearsals (hakpa) — ideal for my research on Eʋe song composition. As Godwin spent most of his time in Accra, my principal teachers and closest friends were Lebene’s master drummer — Frederick Kwasi Dunyo (Kwasi) — and singer-poet-composer — Kwasi Norvor Afornorfe, known more commonly by his nom de plume, Norvor (Nɔvɔ). Frequently I’d visit their respective natal Eʋe villages, Dagbamete and Avenorpedo, near Akatsi in Ghana’s Volta Region (see map).

The Eʋe Drum

Eʋe performances center on a collective compositional structure called ʋu (“Drum”, here capitalized to distinguish it from any musical instrument), with no equivalent in Western music. A Drum is defined by its songs, percussion instruments, rhythms, movements, restrictions on participation, performance contexts, and history. Each Eʋe deity has a Drum; there are Drums for war, and Drums for funerals, Drums for elders and Drums for youth. Old and sacred Drums are typically fixed, while newer or secular Drums change as fresh materials are added. So-called “recreational” Drums, maximizing community participation in song and dance, are performed for enjoyment — and often at funerals. Others require trained dancers, or serve particular religious communities.

Drums are collective, oral compositions, evolving slowly through the addition and subtraction of musical material. Eventually a Drum may change so much that it is renamed, becoming a new Drum. Genealogies emerge as Drums fission, fuse, or transform over time. No musical notation is used, and formal teaching is unusual: songs, rhythms, and dance movements are preserved in memory, transmitted in performance.

Eʋe dance

Eʋe percussion music

The instruments of an Eʋe Drum are percussive, comprising barrel drums, iron bells, and rattles. The standard drum set includes the off-beat kagan, several kidis (responding to the lead drum), and the deeper-voiced sogo, which may function as lead drum, or as responding drum, e.g. when the powerful atsimeʋu enters as lead. Lead drums play “melo-rhythmically” (Nzewi 1974), using a broad tonal-timbral palette. Iron bells include the double-flared gankogui, and the small toke, played with a metal rod. The rattle, called axatse, is a dried gourd wrapped in a mesh of seeds or plastic beads. In a recreational Drum, everyone is encouraged to join in singing and dancing. However, the drumming group is restricted to specialists, usually male.

Musically, the percussion group can be divided into three sections: the ostinato parts (bell, beat, off-beat), the lead or calling part, and the response parts. At its core, performance features three rhythmic ostinati, what Locke (1998) calls “the time,” threading percussion, song, and dance. Whatever their individuality, drummers, dancers, and singers can never stray too far from each other so long as they hold to these threads. The bell rhythm is usually played by gankogui. Axatse and atsikogo (rapping against the side of the atsimeʋu with wooden sticks) often combine bell and beat. The beat is an equidurational rhythm, clapped, danced, and played on bells and rattles; kagan emits an off-beat pattern. Most Eʋe Drums use a 12-pulse bell, the quintessential Eʋe rhythm 2+2+1+2+2+2+1, whose principal beat is 3+3+3+3. Others employ a 16-pulse bell, typically 3+3+4+4+2, with beat4+4+4+4.

Much of Eʋe singing and percussion is based on the call and response form, in which a musical call issued by a leader is appropriately answered by a responsorial chorus. The call and response unit is a succinct statement of unity, sounding the independent relationship between leader and group. Among percussionists, the lead drum issues the call, answered by responding drums, or — in certain Drums — by the dancers. Percussion music is thus naturally divided into short episodes, repetitions of what Kwasi calls “variations”. Each variation is a short melorhythmic composition, which recurs from performance to performance; the complete repertoire of variations is an attribute of the Drum.

Eʋe song

To the Westerner the drumming is probably the most outstanding feature of a [dance] club’s performance, but to the Eʋeawo it is usually the songs. By its songs a club’s individuality and quality are most clearly established. (Ladzekpo and Pantaleoni, 1970:7)

Each Drum is associated with a particular corpus of songs. Shaped by the bell, beat, and text, the song is a dialog of calls and responses, the vocal analogue of the drumming variation. Calls are performed by a select group of leading singers, strong and sonorous voices surrounding their principal, called henɔ (“song mother”), who may also be a poet-composer (hesinɔ, or akayanɔ, “mother of Akaya”, the deity of song). During the performance each lead singer carries a lesi (horse tail) signifying Akaya and used as a conducting baton, to raise enthusiasm and signal transitions. Norvor told me that “when holding [the lesi], it shows you are a leading singer. It is from the ancestors and inspires you to sing more.” Everyone present sings responses, sometimes even while dancing or drumming.

Songs accompanied by drumming, called ʋuʄoha, tend to be short, featuring simple, repetitive texts that are comprehensible despite the hubbub. During the hatsiatsia (“selection of songs”), longer, more poetically elaborate songs are accompanied by bells only. One bell (gaʄoʄo) plays the basic rhythm, while others (gamamla) add improvisations, weaving an intricate filigree. Everyone gathers to sing in a wide, slowly turning circle, dramatizing poetic meanings with arms, hands, and faces.

Texts emphasize themes appropriate to the nature of the Drum, for instance supplication (in religious Drums), praising valor (in war Drums), or expressing loneliness (in funeral Drums), and frequently quote Eʋe proverbs. Songs from venerable ceremonial Eʋe Drums (Atsiagbekɔ, Adzogbo, Kenyo, Gadodo, Kpegisu) or religious Drums (e.g. Drums for Yeve or Afã, deities of thunder and divination, respectively), are ascribed to the ancestors; their repertoires are static, or even decreasing, as songs are forgotten, and new ones are rarely composed.

According to Mr. Agbeli, songs are actively composed today principally for the newer recreational Drums, especially Ageshie (whose frequently lewd songs may be composed extemporaneously), Kinka, Unity, Atsigo (also known as the Akpalu-style, after the famous Eʋe composer; see Awoonor 1974), and Gadzo. Since these Drums are also used for funerals, they are more likely to be associated with a permanent and active group, a benevolent society or club, to which a composer may be affiliated.

Eʋe composers are struck, often abruptly, by inspiration, which typically continues to afflict them throughout their lives. This inspiration is deified as the spirit of singing, Akaya, whose possession can even cause madness. A ritual for Akaya may provide some relief.4 But the urge to do nothing but sing remains strong, and composers have an unfair reputation for laziness. When a composer dies, his or her compositional spirit travels to a near relation. Composing is a gift from God, and from the ancestors, which cannot be refused. Composers often “polish” a song collaboratively, at a closed workshop called havɔlu (“song initiation”; see Dor 2004). Working with Norvor, I observed several havɔlu sessions, with a triple function: (1) teaching the song to the lead singers, facilitating its transmission to the entire society, (2) polishing the song, in text and melody, and (3) providing a forum for important persons to voice criticisms, so that once the song has been brought out, they will have no grounds for raising objections.

Eʋe songs are rarely sung exactly the same way twice. The henɔ can vary the order of song sections, and the number of times each one is repeated. Melodic variation arises with improvisation, and due to variable conceptions of the melody among the singers. Finally, there is microscopic variation at the level of intonation or timbre; Eʋe intonation can be quite wide, and each singer intones the song in his or her own way. Simultaneous variation frequently produces choral homophony.

Lebene’s Kinka Drum

In 1952 the first Eʋe benevolent society in the Accra area was formed at Tema, with Kinka as its principal Drum. Despite a profusion of older members, this society was still called the “Eʋe Youth Association” in 1988, and Kinka is often described as a Drum of the youth. These youth are not just the youth of today — people of all ages take part in Kinka — but also those who first introduced this relatively new recreational Drum, which emerged in the late 1930s. Lebene’s chairman, Franklin Aheto, told me that Kinka was derived from two older Drums, Gahu (Locke 1998), and Oleke. He said that Kinka was brought from the town of Sademe to Avenorpedo by a man named Bali, then lead drummer of the Avenorpedo benevolent society. When Lebene formed in 1974, Bali became lead drummer, and the new society adopted Kinka as well.

Norvor told me that Kinka was brought to Avenorpedo about 1957 by the great composer J.K. Dunyo, who learned Kinka at Tsiame. Thereafter, Dunyo served as principal composer for the Kinka group in Avenorpedo, and later for the Avenorpedo Lebene Habɔbɔ in Ashaiman, until his death in 1983, when he was succeeded by Norvor. As for most Eʋe recreational Drums, an in-house composer provides songs for each Kinka group, and so each group’s music is a bit different.

Today, Norvor (b. 1949) serves as Lebene’s official henɔ and hesinɔ, lead singer and resident poet-composer, though he is a carpenter by profession. Norvor began composing suddenly around the age of 29. He recounted to me the hardship of his musical-poetic gift; when a song comes to him late at night he is unable to sleep until he has worked out its melody and text. He has composed over 50 songs for Kinka, in drumming, hatsiatsia, and “music” styles, as well as many songs for another Drum, Singa. Norvor’s songs express loneliness, isolation, warning, advice, prayers, complaint, suffering, loss and lament. They promote unity, celebrate the nation, and engage in sociopolitical commentary. He has also composed songs (e.g “Melo klo dzi na aʄetɔ” and “Yehowa nye kplɔ la nye”) asserting the compatibility of traditional music with Christianity.

The Kinka percussion ensemble comprises oke, axatse, gankogui, sogo, kidi, kagan, atsimeʋu, and boba, a stout drum with a booming bass voice. Franklin Aheto explained that “Kinka has advantages over other Drums. The rhythm is very lively with the youth of today, more than the traditional Agbadza5...Kinka is more dynamic, partly because boba gives a sort of force.”

Lebene’s Kinka Drum begins with a few songs sung freely by the henɔ and his assistants as they circle the dancing area, lesi in hand. Then the henɔ stands before the percussion ensemble, and sings a song to bring them in. Usually Norvor opens the drumming with Dunyo’s short song, “Nyea me le alɔm̃e”, which recounts inspiration through dream: “I was sleeping when the song called me. I’m going to sing the Kinka song.” After singing the song once or twice, he turns to face the drummers, and begins again, in strict time, vigorously waving his lesi, and whipping its tip in their direction at the end of his call. The bell, rattle, and atsikogo players enter at the beginning of the response, and the Kinka drumming commences with an introduction called adzowɔwɔ, over a 16-pulse timeline. During adzowɔwɔ, kidi and sogo are silent, while atsimeʋu and boba run through some variations, rather like an overture to what will follow. The henɔ continues to lead songs until he signals that the adzowɔwɔ is to end. At this point, atsimeʋu begins to play a special call which brings in the response drums, the rattle players shake their rattles in the air, and there is a general commotion which precludes singing.

During the “music” section, the bell returns to its original 16-pulse pattern, but slightly slower than during the drumming section. “Music” songs are longer and textually more elaborate than drumming songs, though not quite as long as hatsiatsia. As in hatsiatsia, people gather and turn in a circle while singing “music” songs; unlike hatsiatsia, there is sporadic drumming, especially on the small parteka (“part taker”) drum; sometimes the boba or atsimeʋu chime in briefly as well.

The Lebene Kinka Funeral

The Kinka funeral as performed by the Avenorpedo Lebene Habɔbɔ is an elaborate event, comprising a suite of Drums, well-balanced in their pacing and order, together with ritualistic speeches and actions. Segments of Kinka drumming are interspersed with other Drums, whose tempo and character are chosen so as to provide variation.

Urban Eʋe retain strong connections to their home villages, and are usually buried there. Lebene plays every month when a member has died, and with over 600 members someone is likely to die at least every other month. After a death, the society soon convenes to play the traditional funeral Drum, Agbadza, at the deceased’s house, then travels en masse to the home village for the funeral proper, and plays a full Kinka funeral. On the Saturday preceding the first Sunday of the next month which is not already so scheduled, they play an Agbadza wakekeeping6 in Ashaiman, from 2 pm until about 8 pm, followed by another Kinka funeral the following day, from 2 pm until 6 pm.

Lebene’s Executive retains ultimate control of the funeral performance, signalling the henɔ when they want to begin, transition to a different segment, or end. The henɔ is the front-line commander, leading the songs, signalling sectional transitions with his whistle, and setting tempos. He begins each Drum as described earlier for Kinka, first singing a few songs in free time, and then bringing in the percussion with a wave of his lesi.

Nearly equal to the henɔ in responsibility is the master drummer, or azagunɔ, whose primary job is to lead the drummers in an appropriate sequence of variations. Both the lead singer and lead drummer must be ever-vigilant, leading and coordinating singing and drumming, and correcting any mistakes. Their roles require a complete and deep knowledge of the music, and a keen sensitivity to its guiding aesthetics.

Informally, the funeral opens with a prelude of Kinka drumming, drawing a crowd. When the Executive indicates the formal commencement, drumming ceases. One of the elders delivers a short prayer, and an alcoholic libation, usually gin or schnapps, is poured for the deities. Next the henɔ gathers his leading singers, and begins singing for Afã, deity of divination. After a few songs, he signals for fast Afã drumming to commence. Ten minutes or so later, fast Afã is brought to a close, and the henɔ brings in slow Afã in a similar manner. (Nearly all traditional Eʋe performances begin with a libation and at least a token quantity of Afã drumming, in order to consecrate the event and ensure its success.) Following slow Afã comes a fast recreational Drum called Adzrowo. Next comes Kinka in three parts, as described earlier, after which a trained troupe may present a “cultural display”: a dance-drama for the entertainment of the crowd. This display is followed by a venerable Drum “of the forefathers”, the stately Singa. The funeral closes with another Kinka segment, including drumming, hatsiatsia, music, and a final drumming section, if time permits.

Eʋe Aesthetics and Social Solidarity

Yet unity doesn't come at the expense of individuality. On the contrary, Drum performance unifies by liberating individual voices, creative and spontaneous; by empowering idiolects of socio-musical style, enabling personal expressive communication through intensive, interactive variations upon the collectively- held aesthetic forms underlying drumming, dancing, and singing. Parallel expressive communications, through multiple auditory and visual channels, induce ephemeral feedback loops, amplifying the emotional level of performance, and ensuring each participant’s active engagement.

Unity is all the stronger which does not preclude particularity. Such a unity depends on connectivity rather than similarity, joining participants in an affectively- charged web of unmediated socio-musical connections, generating that Durkheimian “collective effervescence” that persists beyond the space-time of performance, forging the durable bonds of group solidarity.

Ɖekawɔwɔ!

— Michael Frishkopf

References

Avorgbedor, Daniel Kodzo. 1998. Rural-urban interchange: the Anlo-Ewe. Garland Encyclopedia of World Music : Volume 1, Africa. Ruth M. Stone, Editor. 389-399.

Awoonor, Kofi. 1974. Guardians of the Sacred Word: Ewe Poetry. New York: Nok Publishers.

Dor, George. 2004. Communal creativity and song ownership in Anlo Ewe musical practice:

the case of havol̲ u. Ethnomusicology. 48 (1): 26-51.

Frishkopf, Michael. 1989. The Character of Eʋe Performance. Thesis (M.A.)—Tufts

University, 1989.

Ladzekpo, Kobla and Hewitt Pantaleoni. 1970. Takaɖa drumming. African Music, 4:6-31.

Locke, David. 1998. Drum Gahu: An Introduction to African Rhythm. Tempe, AZ: White Cliffs

Media.

Nzewi, Meki. 1974. Melo-rhythmic essence and hot rhythm in Nigerian folk music. The

Black Perspective in Music. 2 (1): 23-28.

Notes

1 See http://www.ethnologue.org/show_language.asp?code=ewe

2 The following text is adapted from Frishkopf 1989.

3 Traditional Eʋe acknowledge a single Creator God (Mawu), approached via ritual devotions for a lesser spirit (trɔ or vodu). Starting in the 19th century (especially with the Bremen Mission from 1847) many Eʋe have adopted Christian practices — often alongside traditional ones.

4 The drumming deity Azagu stands in a similar relation to drummers, and similar ceremonies are performed for Azagu.

5 Agbadza is an older Eʋe funeral Drum, originally performed for war.

6 Traditionally, a “wakekeeping” is held the night before a funeral, continuing until dawn. This practice continues in villages. But in the cities thieves used to rob the homes of group members during the night. Accordingly, in Ashaiman “wakekeepings” are held in the afternoon.