1. Why study face perception?

2. Compare the evidence from the holistic and featural approaches to face perception.

3. How do face perception disorders help explain face processing in the brain?

4. What makes a face attractive, and why?

5. What are some effects of facial attractiveness?

6. How does facial attractiveness affect face perception?

• provides important information critical to ______ function: identity, gender, age, facial expression, gaze direction, health, speech

• provides insight into __________ discrimination (not addressed by most theories of object perception)

- __________ discrimination: between members of the same stimulus category

e.g., poodle vs. border collie

- __________ discrimination: between members of different categories

e.g., dog vs. cat

• may inform on the nature of hemispheric processing

- left hemisphere: decomposition/featural processing

- right hemisphere: composition/holistic processing; summation of first-order arrangement and second-order relational information

▸ first-order ___________ information: spatial relations between constituent parts of an object; all faces share common first-order information

e.g., all eyes located above nose

▸ second-order __________ information: relative size of spatial relations between parts of an object; individuals differ on second-order information

e.g., John has closely set eyes, Maria has small nose

• interesting example of object perception in the _______ stream

(Martha Farah et al., 1998; Nancy Kanwisher et al., 2006):

- individual features are only important in that they comprise part of the face context and help make up a whole face

- face perception primarily based on processing holistic information

- proposes face _______: specialized mechanisms for face perception; brain circuits that are not used in the perception of other objects

Evidence:

• newborn infants:

- gaze longer at pictures of mother than of a stranger

- look longer at attractive faces

- can discriminate and imitate facial expressions at 36 hours after birth

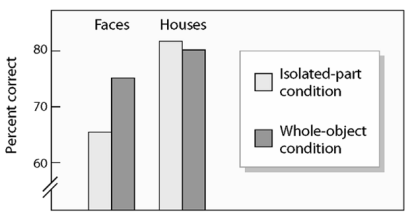

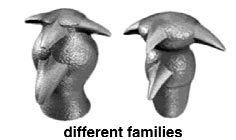

• Tanaka & Farah (1993): part vs. whole

- training phase: showed participants sketches of faces labeled “Larry’s face,” and houses labeled “Bill’s house,” etc.

- recognition test phase: participants asked about the faces and houses

▸ ________-____ condition: given a choice of two object parts, pick which one had been presented before

(e.g., “Which of these is Larry’s nose?” or “Which of these is Bill’s door?”)

▸ _____-______ condition: given a choice of two whole objects, pick out the one they had seen earlier

(e.g., Which of these is Larry’s face?” or “Which of these is Bill’s house?”)

- participants equally good at recognizing parts of houses as whole houses

- for faces, participants were not as good at recognizing face _____ as they were at recognizing _____ faces

- face recognition seems to be ________

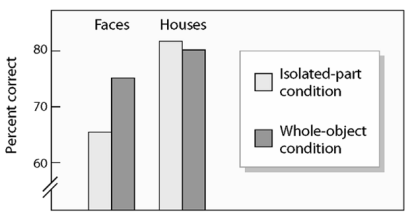

• _________ effect: upside-down faces are more difficult to identify; perception of features is unaffected (Thompson, 1980)

- conclusion: faces are represented as undifferentiated wholes

- inversion interferes with this processing, necessitating feature-by-feature analysis (______, less accurate)

• _________ faces difficult to identify

- upright faces cause strong N200 brainwave in right fusiform gyrus, but not scrambled or inverted faces, cars, or butterflies (Allison et al., 1994)

• neuroimaging studies:

- fusiform face area (FFA) located in right lateral ________ _____ (in inferior temporal lobe)

▸ fMRI found face-specific attention activated FFA more strongly than objects of similar complexity (Kanwisher et al., 1997)

▸ PET scans found right fusiform gyrus activity is greatest during face memorization tasks; activity correlates with performance (Kuskowski & Pardo, 1999)

- face-selective cells also found in amygdala, frontal lobes, and other regions (see below)

• neuropsychology/brain damage:

- _____________: failure in the visual processing of faces which is not due to a general intellectual impairment, sensory impairment, or language disorder

- caused by damage to FFA (or a few other areas)

• double-dissociation of face and object perception:

McNeil & Warrington (1993): case study of W.J.

- severe prosopagnosia due to right hemisphere damage

- normal visual acuity and normal left hemisphere functioning

- was much worse at recognizing famous human faces than individual _____ from a flock he had acquired after acquiring prosopagnosia

- recognition memory performance with unfamiliar _____ surpassed that of normal controls, matched for profession and experience with sheep

- W.J. had face-specific deficit, not generalizable to other classes of complex stimuli

Moscovitch, Winocur, & Behrmann (1997): case study of C.K.

- opposite case of visual object agnosia (cannot identify things visually) with intact face perception

- can identify famous faces and match unfamiliar faces, but cannot distinguish a feather duster and a ____

- when shown paintings of “_____/faces” by Arcimboldo (1527-1593), could not see the _____ for the faces!

This ______-____________ between visual object agnosia and prosopagnosia provides support for the existence of distinct face-processing regions.

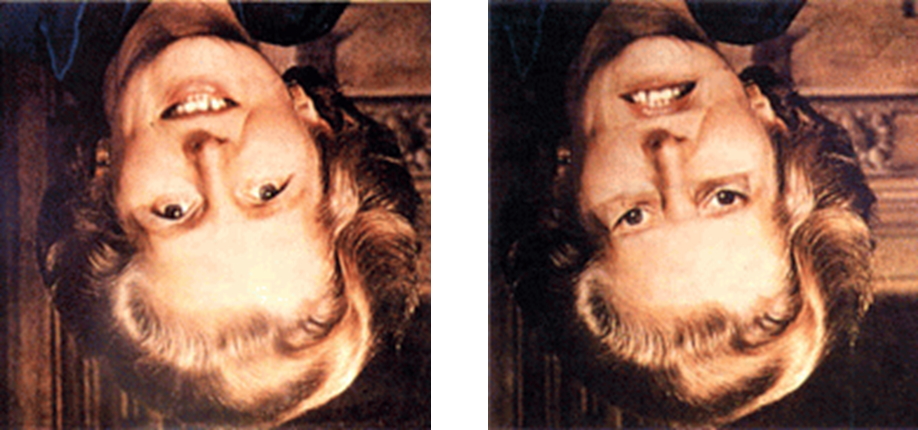

(Isabel Gauthier, Michael Tarr, & colleagues, 1998)

- face processing is just an example of intraclass discrimination; there is nothing special about it--it’s just a result of experience

- face perception primarily based on processing facial ________ (or a combination of features)

e.g., shape or colour of eyes; or shape of chin, nose, and mouth

- there are no specialized brain mechanisms for face perception; it’s no different than differentiating between ____

Evidence:

• right hemisphere-bias for faces not found until age 12: may develop with __________ (Diamond & Carey, 1977)

• inversion effect: inversion interferes with processing because it changes the _______ in which we normally see faces

- Europeans show a greater inversion effect for European than for Asian faces

- viewing ____ elicited an inversion effect comparable to faces, but only for experts--judges with 10 years of experience, and only for their specific breed of expertise (Diamond & Carey, 1986)

• neuroimaging studies:

- in addition to having face selective areas, ventral temporal lobe has areas that prefer other stimuli, like _____, letterstrings, and gratings (Puce et al., 1996)

- occipital face area (OFA) located in inferior occipital gyrus; activated by individual facial features (Arcurio et al., 2012)

- face-selective region in superior temporal sulcus (fSTS) sensitive to face parts, not to correct facial configuration (Liu et al., 2010)

• visual experience:

Gauthier et al. (1999):

- task: classify imaginary, faceless, plantlike creatures called ________ according to sex (plok & glip) and family (samar, osmit, galli, radok, & tasio)

- participants displayed elevated fusiform gyrus activity as they identified pairs of matching Greebles

- only found for Greeble _______ (10 hours of training)

- only for upright Greebles

- right anterior fusiform, another face area, not activated by Greebles at all--may be specialized for faces

• prosopagnosia:

- those with prosopagnosia show deficits in __________ discrimination (Greebles, snowflakes) as well as face perception deficits

- but C.K. (visual object agnosia/intact face perception) could not ____________ Greebles; this does not support the featural view

Prosopagnosia (De Renzi et al., 1991; Gainotti & Marra, 2011; Michelon & Biederman, 2003):

• ____________ prosopagnosia: impairment in basic face perception; patient cannot “see” faces normally, cannot determine they are looking at a face, and hence cannot identify it

“Faces don’t look normal anymore, they are quite distorted and contorted like some sketches [by] Picasso.” (Hecaen & Angelergues, 1962)

- visual association areas within the right occipital and temporal regions implicated

Bodamer (1947): case study of Unteroffizier (Uffz.) S.

- patient unable to identify previously familiar faces, including famous faces, friends, family, and patient’s own face in a ______

- coined the term “_____________”

• ___________ prosopagnosia: can determine they are looking at a face, but associated information (e.g., name) can no longer be retrieved, preventing identification

- right anterior ________ regions implicated

Bruyer et al. (1983): case study of Mr. W.

- 54-year-old Belgian farmer could copy drawings of faces, match faces, determine gender through faces

- poor at ___________ famous faces, and at familiarity judgment of personally known faces

These two types may inform the featural/holistic debate: Face perception may involve both featural and holistic processing.

• apperceptive prosopagnosia may be damaged ________ processing system

• associative prosopagnosia may be damaged ________ processing system

Capgras Syndrome (Capgras & Reboul-Lachaux, 1923):

- delusion that a close relative or friend has been replaced by an exact double--an ________

- impostor is a ___ figure for the patient at time of onset of symptoms (e.g., if married, always the spouse)

- patient may also see himself as his own ______

- may believe that inanimate objects (furniture, a letter, a watch) have been replaced by exact doubles

- not obtained when talking to people on the _____

- associated with brain injury, history of delusions, psychoses (may be ___________ of brain injury and delusion)

- may be failure for recognition to elicit appropriate _________ output

Hirstein & Ramachandran (1997):

- syndrome due to disconnection between face-processing areas in temporal lobe and ________

- hypothesized pathway: fusiform gyrus ![]() superior temporal sulcus (STS)

superior temporal sulcus (STS) ![]() amygdala

amygdala

- this connection aids in perceiving facial expressions of emotion, and feeling emotions in response

- it bypasses areas for semantic interpretation of faces, language areas, etc. in temporal lobe

- thus, unaccustomed lack of _________ response to close relatives interpreted as reaction to impostor

- evidence: those with prosopagnosia have normal GSR (galvanic skin response) to familiar faces, but those with Capgras do not

[What about Figure 10.30 in Snowden et al. (2012)?

It is taken from a paper by Ellis & Lewis (2001), who adapted it from information given in a paper by Haxby et al. (2000), but it is actually based on a model proposed by Bauer (1984) and De Haan et al. (1992).]

Double-dissociation of face perception and emotion (Ellis & Lewis, 2001):

• people with Capgras syndrome can identify faces, but seem to lack an emotional response to them

• people with prosopagnosia cannot identify faces, but may be able to identify emotional facial expressions (Duchaine et al., 2003; Tranel et al., 1988)

Fregoli Delusion (Courbon & Fail, 1927):

- patient has the delusional belief that different people (e.g., strangers) are one single, familiar person (e.g., a famous actor, or a family member) who changes appearance or is in disguise

- patient usually believes this familiar person to be a __________ who is following them

- named for the famous Italian actor Leopoldo Fregoli (1867-1936), who was renowned for his ability to make quick changes of appearance during his stage act

- right anterior fusiform gyrus damage is implicated, as well as temporal lobe locations involved in face recognition (Hudson & Grace, 2000)

Ramachandran & Blakeslee (1998):

- in Capgras syndrome, the problem may be underactivation of normal autonomic arousal

- but in the Fregoli delusion, the problem may be excess inappropriate arousal to viewing unfamiliar faces in temporo-limbic connections

Seeing a pretty face...

...is more important for judgments of attractiveness of the “whole person” than ____ attractiveness

...activates the brain’s reward centres

...motivates sexual behaviour

...elicits positive personality attributions (the “beauty is ____” stereotype)

What makes a face attractive?

• averageness

• symmetry

• sexual __________ (masculinity in female faces, and vice-versa)

• youthfulness

• good ________

• pleasant expression

• liking (for familiar faces)

Averageness:

• Francis Galton (1883):

- created composite images of faces by projecting multiple faces onto a single piece of film

- startlingly, the composites were judged to be ____ attractive than the constituent faces

• Langlois & Roggman (1990):

- computer-generated averaged composites compared to the component faces

- an “_______” face has average trait values for a population

- averages were judged to be more attractive

- as more were added (up to 16), attractiveness increased

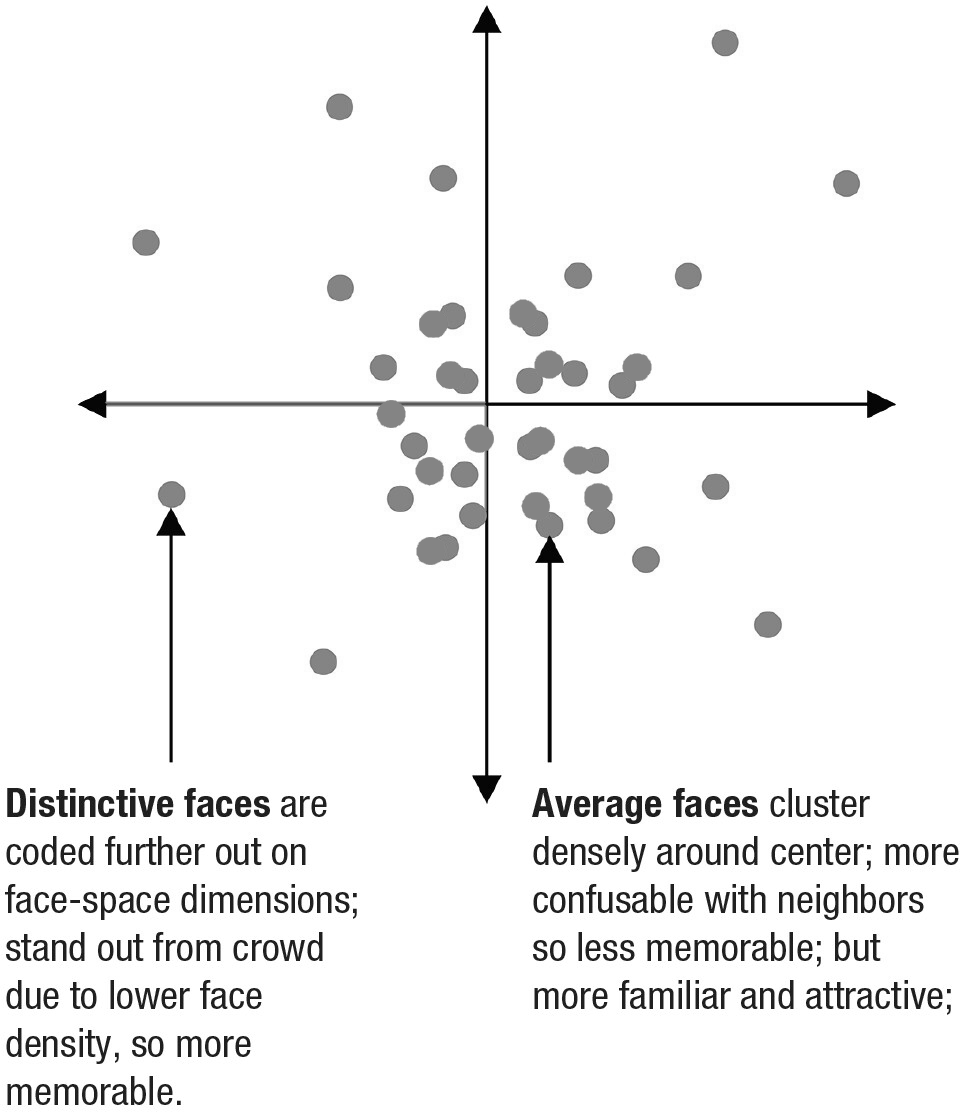

• Face-space theory (Valentine, 1991; Valentine et al., 2016):

- proposes that faces are coded as points in a hypothetical multidimensional space

- average face is located at the centre; faces are normally distributed, so that those closer to the average are more prevalent

Why do we prefer attractive faces?

• ____________ advantage view: attractive face is adaptive for mate choice

- may signal important aspects, like health

- high cross-cultural agreement on attractiveness

- preferences emerge before cultural standards of beauty are learned

• __________ bias view: preference for attractive face is a byproduct of visual information processing

- beauty-in-averageness effect: people tend to prefer highly prototypical stimuli over more unusual exemplars

- average face is similar to mental face _________, thus is more easily processed

Symmetry:

• our genes predispose us to develop symmetrically

• however, disease and infections during development produce asymmetries

• fluctuating asymmetries increase with inbreeding, _________, and developmental delay

• male bilateral (body) symmetry is a better predictor of the likelihood of female ______ than any other factor, including age, wealth, social skills, physical attractiveness, or “being in love” (Thornhill et al., 1995)

• can be used to compare the competing theories:

- evolutionary view: we are attracted to symmetrical faces because they represent ______

- perceptual view: it’s ______ to process symmetrical stimuli, which are thus preferred

• Little & Jones (2003):

- opposite-sex upright faces are “____ ______ ________ stimuli”

- inverted faces are more like “_______”

- evolution hypothesis: preferences for symmetrical faces should be weaker when they are inverted (less mate-relevant)

- perception hypothesis: inversion does not affect symmetry, so preferences should be unchanged

- results:

|

• 57% of upright symmetric faces preferred (vs. upright asymmetric faces) • 52% of inverted symmetric faces preferred (vs. inverted asymmetric faces) |

- modest _______ for evolutionary explanation

Other factors:

• menstrual cycle: women (not taking oral contraceptives) generally prefer feminine male faces, but they are more attracted to masculine male faces around _________

• ____: attractiveness preferences are greater when faces are directing positive social interest at you (i.e., smiling and looking at you), rather than directed at others

Effects of Facial Attractiveness:

• Hamermesh & Abrevaya (2013): happiness

- analyzed data sets from Canada, Germany, UK, and USA

- attractiveness is correlated with happiness and life satisfaction

(for every 1 standard deviation change in beauty, there is a +0.08 (men) or +0.07 (women) standard deviation change in life satisfaction/happiness)

- effect is halved by taking into consideration covariates of educational, marital, and labour-market outcomes (i.e., your level of education, marriage, and job also affect happiness)

- monetary outcomes also have a small effect

• Mocan & Tekin (2006): criminal behaviour

- 15,000 high schoolers were interviewed in 1994, 1996, and 2002 (part of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health)

- interviewers rated the physical appearance of the student on a 5-point scale from “very attractive” to “very unattractive”

- results:

• unattractive individuals commit ____ crime in comparison to average-looking ones

• very attractive individuals commit less crime, compared to average-looking ones

(“I am too ____ to get a job” -- one Miami man’s statement in 2003 as to why he committed robberies)

• Todorov et al. (2005): election results

- participants viewed black & white photos of actual U.S. political candidates (if any faces were recognized, the data was thrown out)

- inferences based only on facial appearance predicted outcomes of elections better than chance

- candidate viewed as more _________ won:

• 72% of Senate races

• 67% of House races

- same inferences drawn when the faces were presented for only 1 second (Willis & Todorov, 2006)

- in contrast, “baby-faced” people who were judged to be less competent than those with more mature faces actually tended to be more ___________ (Montepare & Zebrowitz, 1998)

- Swiss children, asked to choose the “captain of their boat,” chose the winner of French elections 71% of the time (Antonakis & Dalgas, 2009)

Attractiveness and Face Perception:

• Cross et al. (1971): others’ faces

- participants looked at photos of students and teachers taken from high school yearbooks

- were later given a surprise recognition test

- faces judged to be __________ were more likely to be recognized (54% vs. 38%)

• Bower & Karlin (1974): deeper traits

- when faces were judged on deeper _________ traits (e.g., honesty, likeability), and not on surface details like attractiveness, facial recognition improved

• Epley & Whitchurch (2008): your own face

- expt. 1: participant’s face was computer-enhanced to be 20% more (or less) attractive

- attractively morphed face produced faster recognition than actual face (176 ms faster) or unattractive morph (240 ms)

- exp’t 2: when own face was unchanged, uglier, or prettier, participants were more likely to choose the ______ to be their “real” face

- we see our own face as being more attractive than it actually is

“It has been said that a pretty face is a passport. But it’s not, it’s a ____, and it runs out fast.” -- Julie Burchill

(Thanks to Dr Reiko Graham for her contribution to the Face Perception lecture!)