| International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (3) September 2006 |

The Influence of Setting on Findings

Produced in Qualitative Health Research:

A Comparison between Face-to-Face and

Online Discussion Groups about HIV/AIDS

Guendalina Graffigna and A. C. Bosio

Guendalina Graffigna, PhD candidate in Psychology, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore di Milano, Italy

A. C. Bosio, Professor of Social Applied Research and Qualitative Methods, Faculty of Psychology, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore di Milano, Italy

Abstract: The authors focus their analysis in this article on online focus groups (FGs), in an attempt to describe how the setting shapes the conversational features of the discussion and influences data construction. Starting from a review of current dominant viewpoints, they compare face-to-face discussion groups with different formats of online FGs about AIDS, from a discourse analysis perspective. They conducted 2 face-to-face FGs, 2 chats, 2 forums, and 2 forums+plus+chat involving 64 participants aged 18 to 25 and living in Italy. Their findings seem not only to confirm the hypothesis of a general difference between a face-to-face discussion setting and an Internet-mediated one but also reveal differences among the forms of online FG, in terms of both the thematic articulation of discourse and the conversational and relational characteristics of group exchange, suggesting that exchanges on HIV/AIDS are characterized by the setting. This characterization seems to be important for situating the choice of tool, according to research objectives, and for better defining the technical aspects of the research project.

Keywords: focus groups, online focus group, discourse analysis, conversational analysis, HIV/AIDS, youngsters

Author’s note

We thank Franca Giacinti for her helpful suggestions and linguistic assistance. The first author may be contacted at guendalina.graffigna@ unicatt.it

Citation

Graffigna, G., & Bosio, A. C. (2006). The influence of setting on findings produced in qualitative health research: A comparison between face-to-face and online discussion groups about HIV/AIDS. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), Article 5. Retrieved [date] from http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/5_3/html/graffigna.htm

Since the end of the 1970s, qualitative research has been profoundly affected by the emergence of new sociocultural, theoretical, and technological conditions (Bosio, 2000; Denzin & Lincoln, 1994; Gergen & Gergen, 2000). We are referring to constructivism and to critical theories that have highlighted the extent to which social research practices are situated and how every choice and action of the researcher influences research and the data construction process (Appleton & King, 1997; Ashworth, 1996; Guba & Lincoln, 1989). Qualitative research, as it is configured today, is not only the result of theoretical statements or cultural backgrounds but is also the consequence of technological developments influencing research practices. The recent introduction of audiovisual, telephone, information technology, and Internet technologies into research projects have implications with regard to the stimuli used in the data-gathering process, to the possibilities for analyzing results, and, most of all, to the way in which the relationship between the interviewer and interviewees is structured. It is clear that these changes are modifying qualitative research, not only in technical terms but also with respect to the meaning of achieved results (ESOMAR, 1998).

Hence, qualitative research conducted in a virtual setting, which has sparked debate for the past decade among qualitative researchers, above all in the United States, appears to be a particularly challenging case. A great number of authors are fascinated by the potential applications and developments of qualitative research via the Internet (e.g., Mann & Stewart, 2000; Sweet, 2001). On the other side, there are those who dispute its validity and rigor, underlining the need for an in-depth study into how the setting influences the research process (e.g., Greenbaum, 1995, 2000).

In the following article, we will try to cast light on some of the still debated aspects of online qualitative research, particularly regarding online focus groups. We will start from a review of the dominant points of view in the field at present, and then describe the results of a study that compared focus groups conducted face-to-face with Internet-mediated ones.

Before analyzing online focus groups in detail, and their similarities to and differences from face-to-face ones, we will provide a brief description of the traditional focus group technique. The focus group is one of the most widely used qualitative techniques in the field of applied social research (Morgan & Kreuger, 1998). It consists of gathering together a small group of participants (usually between 6 and 10), selected on the basis of chosen characteristics, to have them discuss a planned guide of topics. Guided by a leader (moderator), who encourages the discussion, participants are asked to express, explain, and justify their opinions.

During the group, each participant becomes aware of the others’ points of view on the topic and attempts to state and defend his or her opinions (Agar & MacDonald, 1995); this forms the basis of a negotiation process that makes data collected during the discussion the result of interpersonal exchanges rather than the simple expression of individual perspectives (Frith, 2000; Jarrett, 1993; Smithson, 2000; Zeller, 1993). This dynamic aspect of the discussion is one of the most distinctive but also one of the most widely criticized features of the focus group technique (Frey & Fontana, 1993; Kid & Pashall, 2000). The group setting—implying the physical co-presence of participants—tends to enhance peer group norms and social desirability issues (particularly when the discussion topic is socially sensitive), and it can tend to result in acquiescence and inhibition (Carey & Smith, 1994). In other words, it might not be possible to understand whether opinions declared during the group have arisen from what each participant has to say on the topic or from “conformance or censoring, coercion, conflict avoidance or just plain fickleness” (Duggleby, 2000, p. 294).

In a constructivist perspective, moreover, the interpersonal exchange among participants (with all its positive and negative effects) is considered an important component of the focus group technique. From this standpoint data are “constructed” during the interpersonal exchange, and meanings and accounts are framed, shared, and censured in the interaction among participants (Kitzinger, 1994). Moreover, the discussion’s shape and content are closely related to the context (sociocultural and situational context) in which the focus group takes place. Adopting this epistemological perspective, we felt it interesting to study how focus groups dynamics would change in a nontraditional focus group setting and how this would influence the data construction process.

The Internet has been a fascinating topic of research since it was first introduced. The great amount of easily available information and the opportunity to overcome physical boundaries, reaching people who are geographically dispersed, are just some of the aspects that have made the Internet so intriguing to social researchers. At the beginning, the Internet was considered a new object of research, and several qualitative studies (as well as quantitative ones) were conducted to explore the technical potential of this new medium and its influence on society. For example many studies have been conducted to describe medium realization experiences (Louvieris & Driver, 2001), Internet user profiles (Clarke, 2000), virtual communities’ implicit rules (Ohler, 1996; Turkle, 1995), computer-mediated communication (Joinson, 2001; Meyrowitz, 1985), and so on, but only at the end of the 1990s did qualitative researchers start looking at the Internet as a potential data-gathering tool, setting down some preliminary conditions for the development of a new qualitative strategy—online qualitative research.

Focus groups are the most commonly employed data-gathering method found in the online research setting. The studies that first used online focus groups were carried out in the United States in the 1990s, especially in the marketing research sector (Miller & Walkowski, 2004). The first contribution published on the topic seems to be the article “Cyberspace: Its Impact on the Conventional Way of Doing and Thinking about Research” (Cornick, 1995). This work is a preliminary survey of quantitative studies carried out on the Internet until that time, and its author, Delroy L. Cornick, foresaw a future proliferation of online qualitative studies.

At the same time, the European Society of Marketing Researchers (ESOMAR) also did not delay questioning the feasibility of qualitative research carried out via the Internet in the second Net Effect Conference, in 1999 (Eke & Comely, 1999). However, this was still an exploratory phase, in which online pilot studies were conducted more to experience the online focus group technique than to collect data effectively (e.g., Cheyne, 2000).

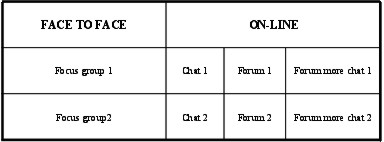

Today, 10 years later, experience with online focus groups is still limited, and little is known about the specificity, advantages, and limitations of this technique. Furthermore, there is no shared definition in the literature of what an online focus group is. The duration and the characteristics of the technology used, the number and type of participants, and the moderating style of a focus group conducted in the virtual setting, for example, seem to depend not only on the research problem and objectives but, above all, on economic factors and the technological resources available. It follows that very different discussions might all be labeled “online focus groups.” For instance, a group discussion can be held via the Internet in the form of a forum, a chat, or a combination of the two ways of—synchronously and asynchronously—communicating to let participants experience different styles of discussion, to discover the one with which they are more at ease (See Table. 1). In short the definition of “online focus group” usually groups together all those techniques that share the main characteristics of text-based computer-mediated communication (CMC), which, according to Riva and Galimberti’s definition (2001), are

In our view, online qualitative researchers must overcome this general state of nondefinition and consider online focus groups as a set of different techniques rather than a data collection strategy. This implies a need for more systematic study of the specific characteristics of these different tools to illuminate more fully the impact of the data-gathering setting on the research process and on data construction (still largely unexplored aspects).

The lack of shared guidelines seems to be the result of the heterogeneity of points of view and the different theoretical and professional backgrounds of the authors interested in online focus groups. Moreover, in the case of online qualitative research, there has tended to be a split between academic reflection and applied research. On the one hand, online focus groups are gaining increased consensus in the professional field, above all in the area of marketing research (Botagelj, Korenini, & Vehovar, 2002; Langer, 2000; Sweet, 2001), whereas in the academic area there has been more scepticism, and only a minority of researchers seem to be adopting or using this technique (Ellett, Lois, & Keffer, 2004; Haigh & Jones, 2005; Keller & Lee, 2003). We need only consider that there are very few academic publications about online focus groups, and that, although the first research using an online focus group was conducted in 1994 (Miller & Walkowski, 2004), the first study was published only in 2000 (Mann & Stewart, 2000), about 6 years after this research practice was used in professional areas.

However, there are also increasing signs of greater openness in the academic area to this technique, especially in health-related qualitative research. In spite of concerns about the ethical aspects of qualitative research via the Internet, more and more authors agree about online focus groups’ potential for the study of sensitive topics. As previous studies on online communication have shown, the Internet allows participants to overcome their inhibitions and social role constraints, thereby promoting freer and more spontaneous interaction1 (Dietz-Uhler & Bishop-Clark, 2002; Galimberti, Ignazi, Vercesi, & Riva, 2001). The anonymity guaranteed by the setting appears to allow contributors to be more open and more willing to disclose private or emotionally involving experiences, as well as making it easier to contact socially excluded or stigmatized populations, who are usually difficult to reach: those affected by AIDS, gay men, sex workers, and people with criminal records, for example (Grady, 2000; Im & Chee, 2003, 2004; Seymour, 2001; Strickland et al., 2003).

The debate about online focus groups is still in its infancy. There are many unsolved questions (When and why should online focus groups be used? How should online focus groups be carried out? What is the validity and what is the practical effectiveness of results achieved in online qualitative research?), and few certain pieces of evidence. It is difficult to summarize the different points of view on the topic, but we can generally say that current remarks about online focus group move in three main directions. The first, assuming an assimilative perspective, considers online qualitative research as a transposition of a traditional focus group into a virtual setting: These authors regard the face-to-face focus group as the optimal model to which an online focus group must refer to be considered a valid research tool. In this perspective, a researcher is asked to guarantee a faithful reproduction of a face-to-face focus group on the Internet, limiting distortions and the loss of fundamental characteristics (Bradford, 2000; Greenbaum, 1998; Holge-Hazelton, 2002; Oshen, 1999). Nowadays, this approach is not used as often as it was in the past—when it was the dominant one—as some authors reckon it fails to express the potential of online qualitative research.

A second line of study focuses on the practical advantages that an Internet-led focus group offers (lower cost, a shorter time for data gathering, and the opportunity to overcome geographical barriers). However, this “pragmatic logic,” already popular in marketing research, does not seem to be sufficient to answer criticism concerning the validity and credibility of this research practice (Botagelj et al., 2002; Cheyne, 2000; Eke & Comely, 1999; Sweet, 2001).

A third and more recent approach seems to involve the adoption of a “differential perspective,” in which the online focus group is considered to be a new, different, and complementary tool in a qualitative researcher’s toolbox. Its supporters believe that a focus group conducted via the Internet has its own specificities that are not reducible to face-to-face focus group characteristics, and they state that it is necessary to look for alternative evaluation criteria, rooted in the framework of online qualitative research, to solve the ongoing debate about its rigor (Gaiser, 1997; Im & Chee, 2004; Schneider, Kerwin, Frechtling, & Vivari, 2002; Strickland et al., 2003).

The third approach to studying online qualitative research seems to us the most fruitful one, because outlining an online focus group’s specific characteristics advantages and limitations helps build the basis for a more conscious choice of tool, in relation to research questions and objectives.

However, online focus groups must be considered not as one tool but as a range of discussion types. As we underlined previously, it is wrong and reductive simply to refer to an online focus group. It seems to us more appropriate to compare a traditional focus group to the different forms of discussion available online (face-to-face vs. forum vs. chat vs. forum+chat).

Furthermore, in a constructivist perspective, it seems necessary to analyze further the research data construction process, both from a thematic point of view (the prevailing approach in the literature and common to the previous three approaches) and from a dynamic one, on the basis of contributions provided by conversational and discourse analysis (Cheek, 2004; Crossley, 2002; Potter & Wetherell, 1987; Powers, 2001) and by Internet-mediated interaction studies (Evans, Wedande, & Van’t Hul, 2001; Galimberti et al., 2001; Herring, 2004; Meyrowitz, 1985), in an effort to describe the peculiar characteristics of conversational exchanges in the different settings. Moreover, in a sociopsychological perspective, we consider the content of the discussion (focus group data) to be the result of interpersonal negotiations among participants, whereby meanings are shared, consensualized, or censured. We also believe that these social processes are shaped by the situation in which the discussion takes place and that each methodological choice regarding the data collection setting would inevitably influence the production of findings. As online focus groups can be considered a new speech context in this respect, we need to reflect on the resources and inner limitations of the setting in which the discussion occurs, analyzing the social exchange that takes place and that is the basis of the data construction process.

We conducted the following study to explore previous aspects and to lay the basis for a better understanding of the online focus group technique. Although the results are circumstantial and not yet definitive, they cast light on some still obscure aspects of the topic. The research method used has allowed us to compare different online focus group formats with traditional ones, all dealing with the theme of young people and HIV/AIDS. As it is now generally agreed that online focus groups are particularly useful for exploring sensitive topics, we chose this research subject because we believed that it could magnify the specific characteristics of the processes activated in the different settings.

That said, we set the following objectives with the intention of exploring the setting influence on the data construction process:

to describe the conversational and relational characteristics of the group exchanges in different discussion settings (in terms of negotiation, cooperation, decision making, and group dynamics) and to understand how the discussion setting can influence the discourse construction (emerging themes, articulation and willingness to disclose private experiences, emotional connotation of the discourse).

For the purpose of a larger and deeper coverage of our research targets, we chose a mixed qualitative research approach combining psychosocial discourse analysis and conversational analysis methods. There exist different definitions of discourse and conversational analysis in the literature, and it is not clear where their boundaries lie. Our view is that the discourse analysis method is an umbrella concept that includes different methods of analysis (such as conversational analysis, psychosocial discourse analysis, and critical discourse analysis). On the basis of this definition (Given, 2005) we adopted a discourse analysis method in our study, integrating the psychosocial discourse analysis method with conversational analysis.

The research scheme was rather complex, as we wanted to compare not only face-to-face and online focus groups, but also different types of online focus groups. We chose to compare face-to-face focus groups with three types of online focus groups: asynchronous online focus groups (forum), synchronous online focus groups (chat), and a mixed type of online focus groups (forum+chat). We conducted two sessions for each format of discussion (face-to-face, chat, forum, forum continued by chat). Having two sessions for each type of setting allowed us to make a within-group comparison in addition to an intergroup one (face-to-face vs. online focus group), using nonquantitative and nonexperimental logic (quantitative and experimental logic would not have made sense in view of the research objectives and the small number of cases), to reach a greater coverage of the analyzed topic. The discussion groups were homogeneous in terms of participant numbers (6-8) and characteristics (youngsters aged 18 to 25 and living in Italy; see “Sample” section), and in terms of moderation guide, but the situational contexts in which they were conducted differed. All discussions involved different participants.

In practice, we carried out the following discussions.

Verbatim notes of all online focus groups (forum, chat, forum+chat) were available in text format, whereas the face-to-face focus groups were transcribed by the researchers.

The moderating style was as nondirected as possible, to let participants express themselves freely, so that we could study the influence of setting on the content and on the articulation of themes. Moreover the same (semistructured) guide was used to moderate all discussions: we decided to have three main interventions on the part of the moderator to guarantee comparability among groups. These were the same for every discussion group:

Each group was made up of 6 to 8 young men and women aged 18 to 25 (we tried to make every group as homogeneous as possible); all members lived in northern Italy.

However, in this case, it seems more appropriate to consider the number of focus groups conducted (two for each discussion format) as our sample. As we sought in this study to explore how conversational exchange and discourse construction patterns are shaped by the discussion setting, we consider groups rather than individuals as our unit of analysis. We therefore have eight units of analysis, six online and two face-to-face: two discussions per setting seem to be the minimum acceptable sample to reach some insights into the topic of study. However this study is the first phase of a more complex research project designed to achieve the objectives described above.3

We recruited the sample using different strategies (posters, snowball technique), and participants were assigned randomly to the different forms of discussion (in some cases also according to their daily schedule). Participants were informed about the purpose, procedure, and benefits/risks of the study and were reassured about privacy and confidentiality issues to obtain their consent. They were also informed about their right to refuse to answer any questions or withdraw from the study at any time. Before every discussion, participants were asked to sign a permission form allowing the researcher to treat collected data in a strictly confidential way. All consent forms—also in the case of online discussion—were signed personally in the presence of research leaders, thereby allowing participants to ask for any clarification they needed. For face-to-face groups, participants were asked to consent to our video- and audiorecording the discussions. Personal data were destroyed at the end of data collection, and discussion transcripts were analyzed anonymously; online discussions were carried out on a private Web site created expressly for data gathering; and every participant was given a personal ID and a password, to guarantee his or her anonymity. Data were stored in the principal investigators’ office and only accessible to them. The names of all participants and any other information identifying them were removed from the data and stored separately.

Figure 2. The research design

All of the transcripts of the eight focus groups were analyzed according to three main strategies:

It is possible to identify some common themes. These are: the importance of prevention, condom use, and the definition of the disease as a social problem rather than a personal one, and they were common to all groups.

However, the articulation and relative weight of these topics and the conversational characteristics of the exchanges appeared different, depending on the data-gathering setting.

We shall here briefly illustrate the main results of our research. We shall first describe the characteristics of the exchange that occurred in each discussion, and then relate them to the content.

Although the face-to-face focus group permitted us to collect a large amount of verbal and nonverbal data, some critical aspects came to light. First, the undoubtedly intense interaction was mainly articulated in alternating dyads (couples of participants), thus inhibiting the construction of a “multiple voices” discourse. Furthermore, the management of turn-taking in the discussions was problematic on several occasions because of the occurrence of leadership phenomena: In both groups, a participant monopolized the talk, keeping his speech turns long and making it necessary for the moderator to intervene.

The co-presence of participants and the “physicalness” of the setting (for example, the presence of cameras and tape recorders) put the emphasis on the social rules of the group and the issue of social desirability. This sometimes prevented the disclosure of personal experiences, and participants tended to distance themselves from the topic of discussion.

Moderator: Any feedback about the discussion experience?

Pt1: good, it was pretty interesting . . .

Pt2: yes, amazing . . . apart from the cameras [they laugh]

Pt1: . . . oh yes . . . knowing that you were recording us doesn’t make me feel very at ease . . . maybe if you hadn’t told us we would be more spontaneous! [He smiles]5

Participants seemed to avoid expressing their points of view, frequently making use of impersonal constructions, such as “people think” and “they say,” and to courtesy formulas.

Pt1: AIDS is a very big problem . . . it’s not just related to sexuality and condoms, but it’s also related to political and ethical issues . . . I mean, it’s not just related to physical and biological aspects . . . the problem is bigger! I think it’s unacceptable that today, in 2003, people still don’t know enough about the virus. Maybe they know how you can contract the infection . . . but they don’t really realize the importance of safe practices. . . . In other words: they don’t see the problem in all its complexity . . . they don’t see the problem in all its aspects . . . But to me the worst thing is that it happens not just in underdeveloped countries, but even here . . .

Participants also maintained a critical and polemical attitude during the groups; they were inclined to dispute others’ interventions rather than collaborating to reach common agreement. This attitude was particularly evident when we asked participants to read our message (see section entitled ’method and research plan); this was criticized in its smallest details rather than being considered as a new stimulus to discussion.

Pt1: I’m shocked by that sentence about transfusion: it says that the risk is “low” . . . it doesn’t say that there is no risk anymore . . .

Pt2: . . . you are right! I didn’t notice . . .

Pt3: . . . so it means that it is very dangerous . . . but “low” . . . what does low mean precisely . . . it’s not clear . . .

It seemed that these conversational characteristics of the exchange influenced its content: In face-to-face focus groups the HIV/AIDS discourse was constructed in a more impersonal way than in other discussion formats (as we will describe below) and participants tended to show their “public persona” more than to freely express their opinions. It followed that reflection on the HIV/AIDS question was mainly ethical and religious. In particular, Roman Catholic sexual ethics were discussed, and this morality was felt to be in conflict with the logic of HIV risk prevention, with the theme of trust and the rules within a couple, above all, meaning that there is a “loyalty conflict” in asking a partner to use a condom or undergo an HIV test.

Pt1: What annoys me is that the Church wants to cover up the problem a little by stating that we must not use contraceptives . . . well, this bothers me, since I think the Catholic Church is a great institution, shared by a great deal of people . . . the Church doesn’t allow me to use contraceptives . . . how can I react [ . . . ]?

Pt2: Because in the end . . . how can I say it . . . ya . . . they, our parents, they raised us in that way . . . that sex is something you cannot talk about . . . for me it’s not easy talking with my mom about that. And asking for suggestions.

Pt3: You cannot ask your partner to do the HIV test...it means that you don’t trust him [ . . . ]!

In the forum, interaction was not as frequent as in the face-to-face focus group, and participants mainly carried out a sort of reflective monologue, developed in messages sent following one another. It was, however possible to note that awareness of the social presence of other group members was good (Galimberti & Riva, 1997).6 Although they interacted very little and used the “reply” button (which allowed them to write directly to reply to or comment on another participant’s message) on only a few occasions, they referred to the content of previous messages, often rewriting the exact words. This dimension is central for the purposes of the present survey, which seeks to clarify whether an online discussion could be effectively defined as a group discussion, and whether the virtual setting does not preclude normal processes and interpersonal dynamics, thus provoking significant data loss from the point of view of qualitative research (Marichiolo et al., 2002).

Moreover, in the forum, the role of social desirability seemed to lose its importance, and the discussion group was experienced as a new “membership group” composed of people similar to oneself: The forum was defined by participants as an area to think and share their thoughts with people whom they were not afraid of being judged by, and this allowed greater openness and freedom of expression, compared to a face-to-face group.

Pt1: Our discussion is almost over and I thank the moderator because this has been a wonderful experience for me; I guess it was a first in my life! This forum allowed me to express my opinions without being afraid of being judged and to think about AIDS as I never have before! Then, reading others’ opinions was a real learning opportunity. I thank you all!

In general, this tendency toward greater disclosure seems dependent on the anonymity guaranteed by the setting, because the participants in online discussions generally seemed less worried about their “public face” and more inclined to express their thoughts and opinions. It is interesting, however, to note how the anonymity issue—and its impact on the shape of the exchange—is perceived differently in each online group format considered.7 As we will see later, the greater disclosure allowed by anonymity is particularly evident in the chat, where members expressed themselves very directly and spontaneously.

It was interesting, then, to observe a certain inclination towards conformity also in the forum, which was different from that found in face-to-face focus groups. It was conformity not to the enlarged social group rules but to a disposition to follow the “rules” given by the first contributions to discussion: their length, rhetorical style, and types of information technology options (for example, to post messages as a “new message” rather than “replying” to someone else’s message, to use the “attachment” device, or to use “emoticons” or other graphic options to express opinions more fully) of different contributions seemed to be the same as the first messages sent to the forum.

Apart from keeping interaction less intense, the asynchrony of the discussion setting, in the end, seems to let participants write their messages quietly, making revisions and corrections before sending them: contributions are complex and grammatically correct, frequently including hypothetical constructions, and their wording is often formal and studied.

I have never talked about AIDS among friends, maybe because there were never any occasions, or maybe because, like many people, we consider AIDS a boring and problematic topic . . . and in the end, I think this is the reason why we are here, participating in research on young people and AIDS! Anyway, if I ran into a risky situation, my first concern would be to do the HIV test straightaway, for my own safety and out of respect for my partner.

However, what I would like to say, and that I haven’t done yet, is that when I meet people in the street, who ask me for a signature in favor of AIDS campaigns, or when I come across drug addicts asking for some help or some money (putting forward any kind of reasons), I avoid them, even if I can understand they mean well . . . and I see that many other people do the same ! I really don’t think I’m right, but maybe the reason is that AIDS is such a scary problem that people try to keep away from it, even avoiding talking about it, thinking that AIDS won’t affect them!

The discourse appears better thought out, and members discussed their opinions in organic, coherent, and position paper–like messages.

It followed that “political” considerations about AIDS dominated: The case of Africa, where an increasing number of children die because of the shortage of care, the lack of real political engagement to tackle the problem, the urgency of financing scientific research to study and produce a vaccine, and the marginalization and helplessness of AIDS-affected people seemed to be the main themes in this kind of discussion.

Pt1: I know that 95% of HIV positive people live in “Poor Countries” . . . in Sub-Saharan Africa alone, three million people die every year . . . and I know that for these people the possibility of surviving is almost non-existent . . . because they can’t have antiretroviral drugs which, if taken daily, could give them hope, as they do for any human being in a “Rich Country.”

Pt2: It’s a shame that governments don’t invest money in scientific research, despite the fact that the HIV vaccine is becoming more and more urgent [ . . . ]!

Pt3: AIDS sufferers are considered different, they can’t get a job, they lose their friends . . . this is a shame . . . but making people change their minds is very difficult [ . . . ]!

The chat debate seemed to be totally different from the others: a “brainstorming” session rather than a real discussion! In fact, participants interacted intensely, continuously introducing new stimuli, ideas, and topics. The speech was fragmentary and very quick, and moved more on lines of content, sometimes provoking episodes of misunderstanding.

Pt1: I don’t have sex

Pt2: prevention!!!!!

Pt3: I think it’s very unusual for young people to talk about AIDS

Pt4: I think we know enough about the virus...

Pt1: I was joking ;-))!

Pt3: Ehi guys . . . what are we talking about???? I got lost!!

The interaction, which was frenetic almost all the time, seemed, however, more democratic than in the face-to-face discussions, because all participants had the same time to express their opinions, taking turns to speak spontaneously, without negotiating with the others. Discussion monopolization was very rare, whereas it often happened that a member took on the role of a second moderator, picking up the thread of talk or calling on those who were talking too much or too little.

In the chat, the moderator was certainly experienced as more present than in previous groups, and was considered the person who eased discussion and acted as a gatekeeper. However, because of the greater spontaneity and democracy of relationships, he was often clearly attacked and criticized.

Moderator, what are you saying? Your question isn’t clear: please try again!!

As a consequence of the inner dynamism of the chat, participants expressed their opinions openly, without roundabout expressions or metaphors, often with very direct interventions that provoked irritation in others: Sometimes episodes of flaming took place (Sproull & Kiesler, 1986), in which the communicative exchange was particularly nervous and characterized by provocations or insults.

Pt1: I learned so much at school about HIV prevention!

Pt2: Me too, it’s not enough but it’s very important!

Pt3: I don’t agree, now at school they just gave us a leaflet saying that if you don’t want to catch the virus you should not have sex! It doesn’t make sense!

Pt2: Anyway this is one way to avoid infection!

Pt3: Pt2, you sound too utopian to me!

Pt2: What are you saying?????

Pt2: Me, a utopian?? You’re joking!!!

The exchange appeared more direct in the chat than in other discussions, and members were more inclined to tell their experiences and emotions, thus giving rise to frequent episodes of reciprocal empathy and emotional support. It followed that the main topics were those of sexual behavior, prevention strategies used, and often unexpressed fears and doubts. In particular, in both chats, one of the dominant themes was condom use, with all its practical and emotional considerations.

Pt: I’m a bit skeptical about using a condom also with my steady partner / this is all true, but which one of us, before making love with his/her girl or boyfriend thinks: “AIDS kills”? / It’s like a reciprocal lack of trust / I think it’s a responsible action.

Pt: I don’t use condoms: condoms are not practical, not comfortable . . . they are a hindrance to pleasure. . . . They smell terrible . . . a smell that lasts hours in your nose.

This appeared to be the most complete and articulate form of discussion, both for the characteristics of conversational exchange and for the content of the talk. In fact, it seemed that the combination of the two communication styles allowed the integration of the two settings’ potentials, getting over their respective limitations. The starting forum permitted members to get to know each other and become acquainted with the information system and with the discussion theme; in the first two days, members seemed to have built a stock of shared knowledge—what was said previously—and to have negotiated fundamental rules of interaction.

These aspects were of primary importance for acquiring a sense of belonging to a group, and they facilitated the pursuit of the discussion. In fact, the chat interaction, although retaining spontaneity and immediacy, resulted in more organized and less fragmentary dialogue than in the single chat. Misunderstandings and disagreements were less frequent, whereas satisfaction with participation in the discussion seemed to be greater.

The forum+chat took the shape of a workgroup whose members cooperated to reach a common agreement.

Pt2: Pt1, you mean that sometimes it happens as in this chat: people pretend that AIDS is a problem related just to those who have paid for sex, who have sex with prostitutes?

Pt3: again about prostitutes: Pt2, please stop!

Pt4: Pt3, forgive him! ;-)

Pt1: good job Pt2: I more or less meant that

In this group, discussion became more articulate, ranging over a variety of considerations: from the most abstract or rational ways of thinking about HIV/AIDS—AIDS seen as a frightening, lethal disease (typically evoked in the forum)—to the concreteness of the account of personal experiences of life—descriptions of strategies personally used to avoid infection (discussed in the chat).

Pt: Hardly anybody uses a condom because it’s uncomfortable and irritating / well, to be frank, after reading what was written in the forum, it seems that everybody uses condoms, but in the end, as the last message said, it isn’t true at all . . . / actually, there are some situations in which AIDS is the last thing you think of, I’m lucky, because I’ve always known my partners very well, but it can happen.

Pt: The chat has just finished . . . And I think we are all responsible guys! I mean: no one excludes the possibility of running across risky situations, like one-night stands but in the end I think none of us have real reasons to be worried, because we know how to cope with that . . . Anyway, I thank the moderator because this discussion has given us the opportunity to think seriously about a problem we always avoid!

Technology is rapidly changing how we communicate and interact with each other in everyday life. At the same time, new communication technologies (for example, mobile phones, videoconferencing, and the Internet) are continually modifying the way we do qualitative research, offering new tools to record, analyze, and collect data. These changes seem to have a strong impact on the research process, and qualitative researchers should question themselves about the specific meaning and consequences of the operations they perform.

In particular, in the case of focus groups, online qualitative research cannot be considered a reproduction of traditional techniques on the Internet but is a different set of tools, with its own peculiar advantages and limitations.

Our study, whose aim was to understand and describe online focus group features, compared traditional face-to-face discussion groups to different formats of Internet discussion (chat, forum, and forum continued by chat)

1. to capture the affinities between face-to-face and online discussion groups to extend the theoretical and practical knowledge reached in the field of traditional focus groups to the online setting and

2. to highlight the differences among face-to-face groups and various formats of online discussion to understand their specific characteristics and to determine the conditions that relate to their choice (research questions, objectives, participants, and so on).

Our findings show that the four discussion formats considered (face-to-face focus group, forum, chat, forum+chat) share some common features (e.g., all discussion techniques produced rich and articulate discourse about HIV/AIDS; some key themes were common in all discussions, even if their articulation and weight varied according to the discussion setting; main interaction and conversation patterns were present in all discussion, albeit with different characteristics according to the discussion setting) which suggest a fundamental comparability between face-to-face and online focus groups. However, each discussion groups showed peculiar characteristics, both in terms of conversational exchange patterns and in terms of discourse structure, not only ascribable to the general difference between face-to-face and Internet-mediated interaction. Far from leading to a definitive conclusion, these results seem to confirm not only the hypothesis of a general difference between a face-to-face discussion setting and an Internet-mediated one but also to reveal interesting differences among the forms of online focus group considered, in terms of both thematic articulation of discourse and conversational and relational characteristics of group exchanges.

| Face-to-Face | Forum | Chat | Forum+Chat | |

| Interpersonal interaction | Intense interaction | Less interaction | Intense but chaotic interaction | Collaborative interaction |

| Group dynamics and sense of belonging | Peer group norms and social desirability issue result in inhibition | Perception of a nonjudgmental group of peers | Less worry about social desirability issues results in disinhibition | Great sense of group belonging |

| Conversational characteristics of the exchange | Difficult turn management and leadership phenomena | Organic and coherent messages (like “position papers”) | Sharp and direct messages (like “brainstorming”) | The exchange assumes the characteristics of both forms of online discussion (forum and chat), getting through their respective limitations |

| Discourse connotation | Impersonal discourses, critical attitude and less disclosure of personal experience and emotions | Reflexive attitude | Great disclosures of personal experience and emotion | Articulate discourse: from abstract (forum) to concrete (chat) |

| Prevailing contents | Ethical and religious reflections on AIDS | Political considerations of AIDS | Condom use and sexual relations | From the rational representation of AIDS as a lethal disease (forum) to description of personal strategies to avoid infection (chat) |

| Table 1. Main characteristics of the discussion formats considered |

Moreover, these specificities led to exchanges on sensitive issues—in particular HIV/AIDS—that were characterized by the discussion setting. This characterization seems to be important in situating the choice of tool, according to research objectives, and to better define the technical aspects of the research project (choice of the number and type of participants, discussion guide, and moderation techniques).

In particular our findings, underlining the peculiarity of each discussion format, suggest the following interesting research implications:

Having said this, this study was not intended to be exhaustive, but it is just a preliminary exploration of the controversial issue of online qualitative research. The findings outlined here need to be confirmed by further analyses and data collection (as mentioned above another two phases of the process are being conducted), with particular focus on some methodological questions that remain unanswered (i.e., the most appropriate length for the discussion forum; the optimal number of participants in the chat; the best combination and sequence of chats and forums in the mixed techniques; the most effective moderation style in each setting). Although these results are preliminary and need verification, they could have some interesting implications for qualitative researchers interested in the influence of the research setting on the data construction process when working with focus groups dealing with HIV/AIDS (or, more generally, with other sensitive topics). In this respect, our findings confirm that online discussions are particularly suitable for studying sensitive topics since, thanks to the anonymity guaranteed by the medium, they elicit a more spontaneous interaction and greater disclosure of private experiences and emotions than face-to-face focus groups. Moreover, we can clearly note that online focus groups are a class of techniques rather than a single tool and that qualitative researchers have to be aware of the main differences between chat, forum and forum+chat discussion groups and of their suitability to specific research topics and to specific aspects of the topic (as we have tried to summarize above).

1. Although the anonymity guaranteed by CMC allows participants to communicate more freely, this does not guarantee participants’ real identities and interviewees can lie about their identity or sex.

2. The message attempted to summarize, in a plain rhetoric style, information about HIV/AIDS which has been the object of recent mass media campaigns in Italy. The provided data were based on epidemiological statistics gathered by the Italian Ministry of Health and on press releases issued by ALA (the Italian Association against AIDS).

3. This study is the first step in a complex research project divided into three phases. An additional eight focus groups (2 face-to-face focus groups, 2 chats, 2 forums, 2 forums+chats) will be conducted on the subject of alcohol abuse and another eight (2 face-to-face focus groups, 2 chats, 2 forums, 2 forums+chats) on the subject of smoking behavior—all involving youngsters (18-25) living in Italy—to describe how the discussion setting shapes interaction among individuals and influences the data construction process in focus groups dealing with sensitive topics related to health.

4. Atlas.ti, which originated in a grounded theory perspective, is a very flexible tool and can be easily adapted to researcher objectives and methodological standpoints (Lonkila, 1995). We agree with Barry that Atlas.ti, like other CAQDAS, is just a tool to support qualitative researchers in their data analysis and that “researchers will be more likely to take what they can from the software and use supplementary non-computerized methods, than to confine themselves to the limitations of computer methods” (Barry, 1998, para. 2.6). As well, Coffey and Atkinson (1996), although they consider CAQDAS software (including Atlas.ti) more useful for analyzing the content than the form and structure of a text, acknowledge there are some advantages in using these applications to analyze the narrative and discursive structure of a speech. This said, we are aware of the inevitable consequences of using Atlas.ti in terms of the production of findings. This is why, in attempting to minimize the distortions in our data analysis, we have continuously gone back and forth between paper- and software-based analysis.

5. The following excerpts of group transcripts have been translated into English by the authors for publication purposes.

6. We here refer to Galimberti and Riva’s (1997) definition, according to which the awareness of the social presence of other participants is psychologically similar to an individual’s perception of other group members. Although this perceptive dimension can be considered obvious in a setting of face-to-face discussions, it becomes very important when communication is mediated by a computer; it shows the level at which the speaker with whom people interact in advance is psychologically experienced as if he was in their proximity.

7. In the forum discussion the spontaneity and directness allowed by anonymity was moderated by the asynchronicity of the interaction, which gave participants the opportunity to gauge their comments better.

Agar, M., & Macdonald, J. (1995). Focus groups and ethnography. Human Organizations, 54(1), 78-86.

Appleton, J. V., & King, L. (1997). Constructivism: A naturalistic methodology for nursing inquiry. Advances in Nursing Science, 20(2), 13-22.

Ashworth, P. D. (1997). The variety of qualitative research part two: Non-positivist approaches. Nurse Education Today, 17, 219-224.

Barry, C. A. (1998). Choosing qualitative data analysis software: Atlas/ti and Nudist compared. Sociological Research Online, 3(3). Retrieved May 15, 2006, from http://www.socresonline.org.uk/socresonline/3/3/4.html

Bosio, A. C. (2000). Gli sviluppi della ricerca sociale qualitativa e le condizioni di campo dell’intervista. In G. Trentini (Ed.), Oltre l’Intervista: Il colloquio nei contesti sociali (pp. 341-367). Torino, Italy: ISEDI.

Botagelj, Z., Korenini, B., & Vehovar, V. (2002). The integration power of the intelligent banner advertising network and survey research. In ESOMAR, Net Effects (Vol 5, pp. 161-182). Amsterdam: ESOMAR.

Bradford, P. D. (2000). Online focus group: Technology is virtually there. In ESOMAR, Net Effects (Vol. 3, pp. 181-198). Amsterdam: ESOMAR.

Carey, M. A., & Smith, M. W. (1994). Capturing the group affect in focus groups: A special concern in analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 4, 123-127.

Cheek, J. (2004). At the margins: Discourse analysis and qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 14(8), 1140-1150.

Cheyne, T. (2000). Research through relationships. ESOMAR, Net Effects, (Vol. 3, pp. 209-226). Amsterdam: ESOMAR

Clarke P. (2000). The Internet as a medium for qualitative research. Retrieved October 24, 2005, from http://www.und.ac.za/users/clarke/web/pc.pdf

Coffey, A., & Atkinson, P. (1996). Making sense of qualitative data analysis: Complementary strategies. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

Cornick, D. L. (1995, April). Cyberspace: Its impact on the conventional way of doing and thinking about research. Paper presented at the Sixth Annual Conference of the Urban Business Association. Retrieved October 24, 2005, from http://www.csaf.org/cyber.htm

Crossley, M. L. (2002). Could you please pass one of those health leaflets along?: Exploring health morality and resistance through focus groups. Social Science & Medicine, 55, 1472-1483.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Handbook of qualitative research. London: Sage.

Dietz-Uhler B., & Bishop-Clark C. (2002). The psychology of computer-mediated communication: Four classroom activities. Source Psychology Learning & Teaching, 2(1), 25-31.

Di Fraia, G. (2004). e-Research. Laterza, Italy: Bari.

Duggleby, W. (2000). What about focus group interaction data? Qualitative Health Research, 15(6), 832-840.

Eke, V., & Comely, P. (1999, February). Moderated email groups: Computing magazine case study. Paper presented at the ESOMAR Net Effects 2 Conference, Amsterdam. Retrieved October 4, 2006, from http://www.virtualsurveys.com/news/papers/paper_5.asp

Ellett, C. M. L., Lois, J., & Keffer, J. (2004). Ethical and legal issues of conducting nursing research via the Internet. Journal of Professional Nursing, 20(1), 68-74.

ESOMAR (1998). The worldwide Internet Seminar. Amsterdam: ESOMAR.

Evans, M., Wedande, G., & Van’t Hul, S. (2001). Consumer interaction in the virtual era: Some qualitative insights. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 4(3), 150-159.

Frey, J. H., & Fontana, A. (1993). The group interview in social research. In D. L Morgan (Ed.), Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art (pp. 20-35). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Frith, H. (2000). Focusing on sex: Using focus group in sex research. Sexualities, 3(3), 275-297.

Gaiser, T. J. (1997). Conducting on-line focus group: A methodological discussion. Social Science Computer Review, 15(2), 135-144.

Galimberti C., Ignazi S., Vercesi P., & Riva, G. (2001). Communication and cooperation in networked environments: An experimental analysis. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 4, 131-146.

Galimberti, C., & Riva, G. (1997). La comunicazione virtuale: Dal computer alle reti telematiche—Nuove forme di interazione sociale. Milano, Italy: Guerini e Associati.

Gergen, M. M., & Gergen, K. J. (2000). Qualitative inquiry: Tension and transformation. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 138-157). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Given, L. M. (2005, July). An introduction to discourse analysis. Paper presented at the Fifth Annual Thinking Qualitatively Workshop Series, International Institute for Qualitative Methodology, Edmonton, Canada.

Grady, H. (2000, November). Virtual focus group: A methodological assessment. Paper presented at the Midwest Association for Public Opinion Research Annual Convention, Chicago.

Greenbaum T. (1995). Focus groups on the Internet: An interesting idea but not a good one. Quirk’s Marketing Research Review, Article 0136. Retrieved October 24, 2005, from http://www.groupsplus.com/pages/interest.htm

Greenbaum T. (1998, July). Internet focus groups are not focus groups—So don’t call them that. Quirk’s Marketing Research Review. Retrieved October 24, 2005, from http://www.groupsplus.com/pages/qmrr0798.htm

Greenbaum T. (2000, February 14). Focus groups vs. online. Advertising Age. Retrieved October 4, 2006, from http://www.groupsplus.com/pages/adage0214.htm

Guba E. G., & Lincoln Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. London: Sage.

Haigh, C., & Jones, N. A. (2005). An overview of the ethics of cyber-space research and the implication for nurse educators. Nurse Education Today, 25, 3-8.

Herring, S. C. (2004). Computer mediated discourse analysis: An approach to researching online behavior. In S. A. Barab, R. Kling, & J. H. Gray (Eds.), Designing for virtual communities in the service of learning (pp. 338-403). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Holge-Hazelton, B. (2002). The Internet: A new field for qualitative inquiry. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(2). Retrieved October 24, 2005, from http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/2-02/2-02holgehazelton-e.pdf

Im, E., & Chee, W. (2003). A feminist issues in email group discussion. Advances in Nursing Science, 26, 287-298.

Im, E., & Chee, W. (2004). Issues in Internet survey research among cancer patients. Cancer Nursing, 27(1) 34-44.

Jarrett, R. (1993). Focus group interviewing with low-income minority populations. In D. Morgan (Ed.), Successful focus groups (pp. 184-201). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Joinson, A. N. (2001). Self-disclosure in computer mediated communication: The role of self –awareness and visual anonymity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 177-192.

Keller, H. E., & Lee, S. (2003). Ethical issues surrounding human participants research using the Internet. Ethics & Behavior, 13(3), 211-219.

Kid, P. S., & Parshall, M. B. (2000). Getting the focus and the group: Enhancing analytical rigor in focus group research. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 293-308.

Kitzinger, J. (1994). Focus groups: Method or madness? In M. Boulton (Ed.), Challenge and innovation: Methodological advances in social research on HIV/AIDS (pp. 159-175). London: Taylor & Francis.

Langer, J. (2000). “On” and “offline” focus groups: Claims, questions. Marketing News, 34(12), H38.

Lonkila, M. (1995) Grounded theory as an emerging paradigm for computer-assisted qualitative data analysis. In U. Kelle (Ed.), Computer-aided qualitative data analysis. London: Sage.

Louvieris, P., & Driver, J. (2001). New frontiers in cybersegmentation: Marketing success in cyberspace depends on IP address. Qualitative Marketing Research, An International Journal, 4(3), 169-181.

Mann, C., & Stewart, F. (2000). Internet communication and qualitative research: A handbook for researching on-line. London: Sage.

Marichiolo, F., Bonaiuto, M., Cornacchia, M., Mastrodonato, M., Avalle, F., & Pucci, A. (2002). La videopresenza dell’interlocutore in un sistema di chat-line. In M. Bonaiuto (Ed.), Conversazioni virtuali: Come le nuove tecnologie cambiano il nostro modo di comunicare con gli altri (pp. 126-170). Milano, Italy: Guerini & Associati.

Mason, J. (1996). Qualitative researching. London: Sage.

Meyrowitz, J. (1985). No sense of place: The impact of electronic media on social behavior. New York: Oxford University Press.

Miller T. W., & Walkowski J. (2004). Qualitative research online. Milton Keynes, UK: Research Publisher LLC.

Morgan, D. L & Kreuger, R. A. (1998). The focus group kit. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ohler, J. B. (September 1996). A case study of online community. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 57(3-B), 2221.

Oshen, G. (1999) Online vs. traditional focus groups. Interviewing Services of America, Inc., 22.

Potter, J. & Wetherell M. (1987). Discourse and social psychology: Beyond attitudes and behaviour. London: Sage

Powers, P. (2001). The methodology of discourse analysis. New York: Jones and Bartlett.

Schneider, S. J., Kerwin, J., Frechtling, J., & Vivari, B. A (2002). Characteristics of the discussion in online and face-to-face focus groups. Social Science Computer Review, 20(1), 31-42.

Seymour, W. S. (2001). In the flesh or online?: Exploring qualitative research methodologies. Qualitative Research, 1(2), 147-168.

Silverman, D. (2000). Doing qualitative research: A practical guide. London: Sage.

Smithson, J. (2000). Using and analyzing focus groups: Limitations and possibilities. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 3, 103-119.

Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1986). Reducing social context cues: Electronic mail in organizational communication. Management Science, 32, 1492-1512.

Strickland, O. L., Moloney, M. F., Diethrich, A. S., Myerburg, S., Cotsonis, G. A., & Johnson, R. V. (2003). Measurement issues related to data collection on the World Wide Web. Advances in Nursing Science, 26(4), 246-256.

Sweet C. (2001). Designing and conducting virtual focus group. Qualitative Market Research: an International Journal, 4(3), 130-135.

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the screen: Identity in the age of Internet. London: Weindenfeld & Nicolson.

Zeller, R. A. (1993). focus group research on sensitive topics: Setting the agenda without setting the agenda. In D. L. Morgan (Ed.), Successful focus group: Advancing the state of the art (pp. 167-184). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Weitzman, E., & Miles, M. (1995). Computer programs for qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

| International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (3) September2006 http://www.ualberta.ca/~ijqm/ |