| International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (3) September 2005 |

Racism and Ethnocentrism: Social Representations of Preservice Teachers in the Context of Multi- and Intercultural Education

Nicole Carignan, Michael Sanders, and Roland G. Pourdavood

Nicole Carignan, PhD, Associate Professor, Intercultural Education and Comparative Education, University of Quebec at Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Michael Sanders, PhD, Assistant Professor, Social Issues in Education, Qualitative Research, and Gifted Education, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio

Roland G. Pourdavood, PhD, Associate Professor, Mathematics Education, Cleveland State University,Cleveland, Ohio

Abstract: Using a constructivist inquiry paradigm, the authors attempted in their content analysis to understand the social representations on race and ethnocentrism of preservice secondary teachers studying in an urban university in a Midwest city in the United States. Although social representations can be understood as something in which our participants deeply believe, this study suggests that racial and ethnocentric biases should be examined in the context of multi- and intercultural education. The authors favor a way of revisiting taken-for-granted ideas toward traditional, liberal, and critical or radical multiculturalism. They argue for the recognition not only of the differences and diversity of students (multicultural perspective) but also of the way in which teachers understand, communicate, and interact with them (intercultural perspective).

Keywords: racism, ethnocentrism, multicultural education, intercultural education, teacher education, teaching/learning pedagogical practices, constructivist inquiry

Citation

Carignan, N., Sanders, M., & Pourdavood, R. G. (2005). Racism and ethnocentrism: Social representations of preservice teachers in the context of multi- and intercultural education. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(3), Article 1. Retrieved [insert date] from http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/ backissues/4_3/html/carignan.htm

Viewing school systems from top to bottom, one finds . . . Superintendents are overwhelmingly White and male (95%)…women and men of color in school administration tend to be elementary school principals, central office staff, or administrators charged with duties related to Title IX, desegregation, and so forth. Over 90% of teachers are White, and this percentage is increasing. Over 80% of elementary school teachers are female; mathematics, science, and industrial arts teachers are predominantly male, whereas foreign language, English, and home economics teachers tend to be female. People of color are often custodians and aides, and over 90% of secretaries are women.

—C. E. Sleeter & C. A. Grant, 1994, pp. 29-30

Prospective teachers grow up mostly in middle-class families and are from White communities (Tellez, Hlebowitsh, Cohen, & Norwood, 1995). Meanwhile, by the year 2020, almost one third of the school-age population will be non-White children, and almost one fourth will live in economic poverty, of whom more than half will be White. The organizational structure of these social facts is not neutral. The challenges of a more democratic and inclusive society should invite us to reflect on establishing a sound multicultural teacher education curriculum. As Larkin and Sleeter (1995) have pointed out,

most of the students’ education is conducted within a narrow dominant-culture perspective [and] curricular issues are part of a broader agenda that must be addressed by teacher education programs willing to face the challenges of cultural diversity and educational equity. [This approach proposes] the assumption that multicultural education represents a basic reconceptualization of the process of preparing future teachers. (p. viii-ix)

Inspired by a constructivist inquiry paradigm, we aimed through our content analysis to understand the social representations on race and ethnocentrism of preservice secondary teachers studying in an urban university in a Midwest city in the United States. Social representations can be understood as something in which our participants deeply believe; however, the work presented here indicates that racial and ethnocentric biases should be examined in the context of multi- and intercultural education. We present here a way of revisiting taken-for-granted ideas toward racism and ethnocentrism and argue that not only the diversity of and differences between students (multicultural perspective) but also the way in which teachers understand, communicate, and interact with them (intercultural perspective) should be recognized. Therefore, our central question is What are the social representations on race and ethnocentrism of preservice teachers studying in an urban university in a Midwest city of the United States? In the context of our study, preservice teachers are university students engaged in the process of their secondary school teaching certification. From this question, we want to consider two main goals:

1. identifying the social representations on racism and ethnocentrism of preservice secondary teachers studying in an urban university and

2. understanding these social representations on racism and ethnocentrism of preservice secondary teachers regarding the tripartite multicultural education framework: traditional, liberal, and critical/radical.

We believe that there is an urgent need to favor a socially equitable and culturally diverse education as well as a sound preservice secondary teacher preparation. In the following, we present the conceptual perspective regarding multi- and intercultural education and social representations, the study design, and the methodological framework, as well as the description and the data analysis.

Associated with the civil rights movement in the 1960s, multiculturalism is a political position that emphasizes the recognition of ethnocultural differences for a more equitable society in the United States but also among others in Australia, Canada, Great Britain, and New Zealand. To understand multiculturalism, we will discuss the mechanisms of racism and of ethnocentrism that challenge multiculturalism in education.

What are the mechanisms of racism? According to Taguieff (1997), biological or essentialist racism denies to all human beings the possibility of sharing the same humanity. Consequently, the difference becomes a stigmatization or a symbolic exclusion that allows a group of people to consider itself as superior by looking down at another group and setting up negative stereotypes. As a result, racism is based on a hierarchy of physical differences. In fact, racism is not only a network of attitudes, beliefs, and convictions; it also refers to behaviors, practices, and actions. Racism is a social construction (Exama, 2005; Moussa, 2003). According to Gould, cited by Pollock (2001),

racism in the United States has relied upon naturalizing a racialized hierarchy of academic and intellectual potential ever since racial categories were created and solidified with pseudo-science . . . American racism has always framed racial achievement patterns as natural facts . . . we must acknowledge that the naturalization of such patterns is endemic to American schooling discourse, including academic research . . . who [several American researchers] argue explicitly and passionately that racial patterns are never natural orders, and that they thus can and must be collectively dismantled. (pp. 9-10)

Associated with Gould’s thought, research on deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) points out the irrelevance of using the term of race, because under the skin, we are not able to see who is who.

For understanding the mechanisms of racism, we need to consider the roots of prejudices and of stereotypes that are associated with categories we grew up with, learned, and experienced. Stereotypes are connected to attitudes, beliefs, and values, whereas prejudices refer to opinions without any critical judgment (Allport, 1979). Stereotypes and prejudices are part of the elaboration of social norms. A stereotype is a sort of shortcut, often based on previous experiences or beliefs, whereas prejudice is a preconceived idea, a prejudgment of someone or something. Both stereotypes and prejudices contribute to the elaboration of racism as well as ethnocentrism.

Ethnocentrism refers to the way we look at the world from our perspective or from our filter of meaning (McAndrew, 1986). Here, we use our as a collective identity. It assumes that our understanding is the only valuable understanding. As an example, the Western world representing the supposedly universal perspective from the Enlightenment is considered a standard or norm, whereas the non-Western world—constituted of many other worlds—represents the particular: a kind of suprauniversal culture versus many peripheral cultures. Preiswerk and Perrot (1975) identified ethnocentric biases as the way of putting our sociocultural group and its values in a central position. Arcand and Vincent (1981) also found that the representation of indigenous peoples in Western history schoolbooks is always stereotyped, prejudiced, and marginalized, because the norm that is used to describe their values and to recognize their contribution refers to this universal norm: It is ethnocentrically biased. As a result, indigenous peoples are represented as inferior, primitive, savage, uncivilized, barbaric, and so on, incapable of being civilized and incapable of facing the challenges of a modern society. Rather, close to nature and the past, they are always presented away from civilization and the present. Ethnocentrism is the “we and the others” perspective: the way that the “we” looks at the world while looking down at the mimetic others.

Similarly, Banks (1999) defined Eurocentrism as a colonial perspective in which European values are seen as culturally centric heritages, histories, and cultures of European descendants who live in the United States and elsewhere. Although these hierarchical worldviews are still common, the above authors consider the notion of decentrism as passing from “our” sociocultural references to adequate ways of entering “a” particular ethnocultural sphere.

Multicultural education relates to recognition of values, lifestyles, and symbolic representations. It is an approach to teaching and learning that is, from Bennett’s (1999) point of view,

based upon democratic values and beliefs, and affirms cultural pluralism within culturally diverse societies . . . It is based on the assumption that the primary goal of public education is to foster the intellectual, social, and personal development of virtually all students to their highest potential. Multicultural education . . . [includes] . . . the movement toward equity, curriculum reform, the process of becoming interculturally competent, and the commitment to combat prejudice and discrimination, especially racism. (p. 11, emphasis in original)

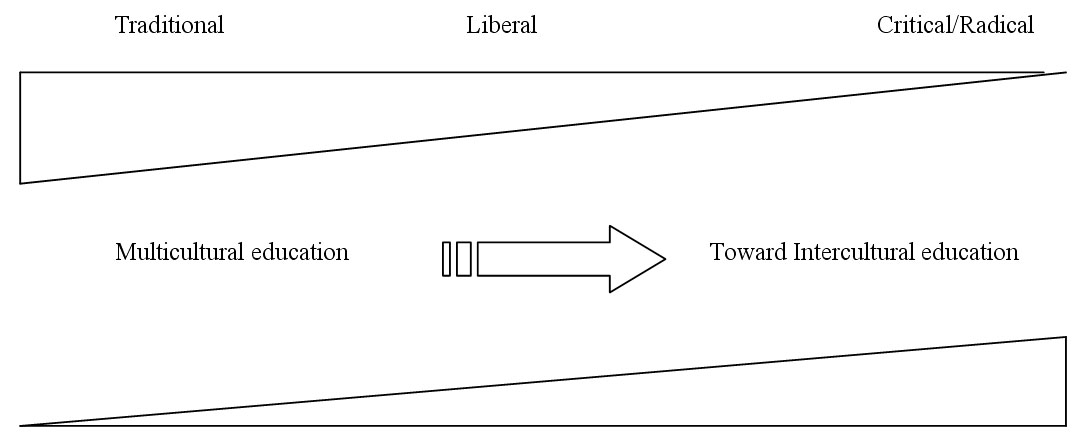

Although the promises of multicultural policies are left unrealized, multicultural education continues to focus on adaptation of the school; intercultural education refers to interdependence among people (Ghaffari, 2000) and emphasizes interaction, interrelationship, exchange, reciprocity, and solidarity. The intercultural dynamics are also related to the aspects of time and space. The notion of time refers to the recognition of the past, present, and future of human realization, contribution, and civilization. The notion of space refers to interactions that occur within a culture and among cultures (Ollivier, 1988). Inspired by Hoffman (1996) and McLaren (1995), we examine three positions in the debate of multi- and intercultural education: traditional, liberal, and critical or radical (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual guidelines

The first position is what we have often called conservative multiculturalism in education. Socially, it refers to an antagonistic tension between the recognition of diversity with the risk of fragmentation and the necessity of defining a common society with the affirmation of a national identity. Using traditional multicultural tenets, we have a tendency to see culture as fixed, essentialist, and predetermined (Taguieff, 1997). Because for them, culture is out there, they promote assimilation (Hannoun, 1987). They believe in a hierarchically superior universal culture, and, on the other hand, they think that some cultures have to be subordinated because of their inferiority. Indeed, what one assumes as being a universal culture is the manifestation of Western-centrism. This view has failed to “promote a systematic critique of the ideology of ‘Westernness’ that is ascendant in curriculum and pedagogical practices in education . . . [although its] proponents articulate a language of inclusion” (McCarthy, 1994, p. 89). In fact, the consequences are the perpetuation of established groups’ hegemony and the marginalization of disadvantaged or segregated groups. In education, it favors the reproduction of the value of the mainstream society or “cultural reproduction” (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1970). From the traditional perspective, neither mechanisms of racism nor ethnocentric biases regarding Occidentalism, Westernness, or Eurocentrism are requestioned. Hence, from the traditional perspective, the world is as it is.

The liberal multicultural education values cultural pluralism which is, according to Bennett (1999),

an ideal state of societal conditions characterized by equity and mutual respect among existing cultural groups. It contrasts sharply with cultural assimilation, or “melting pot” images, where ethnic minorities are expected to give up their traditions and blend in or be absorbed by the mainstream society or predominant culture. (p. 11)

For Grant (1978), multicultural education proposes to adapt curricula, teaching styles, learning strategies, and communication between school and families. Also, it favors the adaptation of school to the needs of students and parents. It is not new that most teachers try to incorporate some aspects of cultural diversity, such as diversity of religions, bilingual education, typology of racism, and reflection on the impact of ethnocentrism.

Based on the willingness to diversify the curriculum and add cultural contents, this approach favors differences and similarities without trivializing and folklorizing cultures proposed in the curriculum. Banks (1999) assumed that ideas and practices have to be included throughout all aspects of the curriculum. In such reality, teachers will need to be prepared to understand students from different backgrounds, to teach content that does not represent mainstream culture only, and to learn to communicate with parents. This position sees culture not as fixed and essentialist, as in the traditional position, but, rather, as dynamic and flexible. From the liberal perspective, mechanisms of racism requestion the social construction of superiority and inferiority, discrimination, and exclusion based on physical or ethnic differences, whereas ethnocentric biases revisit the perspective of universality. Hence, from the liberal perspective, the world might be different.

In critical-radical multicultural education, an attempt is made to resist capitalist values of blind mass consumption and hegemonic power as well as criticize a dominant Occidental worldview that supports inequity. Criticizing the modern society, Sleeter and Grant (1994) aimed at “the elimination of oppression of one group of people by another . . . [and] . . . that the entire educational program is redesigned to reflect the concerns of diverse cultural groups” (p. 209). This perspective suggests that all students take into consideration all aspects of educational practices, including curriculum concerns, instruction, different aspects of the classroom, and support for the regular classroom to adapt as much diversity as possible and other school-wide features. These features can “involve students in democratic decision making . . . involve lower-class and minority parents actively . . . involve schools in local community action projects . . . include diverse racial, gender, and disability groups in non-traditional roles” (p. 211). Sleeter and Grant pointed out that school goals have to “prepare citizens to work actively toward social structural equality; promote cultural pluralism and alternative life styles; promote equal opportunity in the school” (p. 211). Although some authors have insisted on the development of learning skills for becoming critical, conscious, and active socially, others have focused on establishing congruence between what happens inside and outside of classrooms regarding students’ sociocultural background. For them, a multicultural education is political or social reconstructionist.

Therefore, the movement toward equity targets issues of accessibility to a rich and sound curriculum, within which all students will represent themselves when they attend school and, later, when they project their active and successful lives as wise citizens refuting predeterminism. Besides the denunciation of injustice and oppression, another premise concerns communication, relation, interaction, and interdependency when two cultures are in contact. To express this view, some authors have used the term intercultural education (Camilleri & Cohen-Emerique, 1989; Carignan, 1996; Hannoun, 1987; Ollivier, 1988; Ouellet, 1991). Although the term multicultural education is more common in the United States today, the term intercultural education was used 70 years ago. The Bureau for Intercultural Education, which operated from 1934 to 1954, was the brainchild of Rachel Davis DuBois, who expanded her classroom praxis in New Jersey schools. The Bureau assisted primarily in the education of second-generation children of immigrants. It offered a vision of an intercultural nation that was tolerant of diverse peoples (Lal, 2004) and demonstrates that intercultural education is not a recent preoccupation about diversity and equity among teachers .

Instead of focusing on the accommodation of several cultures demarcated by differences, intercultural education is an attempt to understand the impact of the outside word on the school environment. It is an attempt to decorticate mechanisms of racism and of ethnocentrism in favor of more suitable ways of learning to live together in pluralistic and postmodern societies. It promotes diversity, tolerance, freedom, democracy, and interdependency (Linn, 1996).

In that sense, intercultural education expresses that to understand fully a cultural manifestation or phenomenon, we cannot separate it from its cultural bearers or actors. Intercultural education explores alternative ways of communicating (Camilleri & Cohen-Emerique, 1989) that engage all of us in the process of transformation: accepting to transform and to be transformed by those with whom we interact. From the critical-radical perspective, racial and ethnocentric biases are not only requestioned but also involved in transformative actions regarding all aspects of educational practices and social changes that are pluriethnic, pluricultural, democratic, equitable, and inclusive. Hence, from the critical-radical perspective, the world must change.

The process of becoming a multi- or interculturally competent teacher includes the commitment to denounce stereotypes, prejudices, and discrimination, as well as racist attitudes and ethnocentric biases toward transformative actions at school and in the society. Now that we have clarified this perspective concerning multi- or intercultural education, it is easier to discuss the notions of social representations.

As a form of commonsense knowledge and way of thinking that can be learned (Jodelet, 1991), social representation is built from our experiences and transmitted through heritage, tradition, education, and social communication. Social representation aims to organize practices, actions, and ways of communicating. It also helps to establish the vision of participating in a community (Carignan, 1996; Sanders & Carignan, 2003), structure the symbolic process in relation to a social interaction (Doise, 1990), and connect to a collective representation. The sociocultural imprint of content and processes of representation refer to the conditions and contexts in which they emerge to the functions they serve (Martin Sanchez, 2000). It is a sort of referentiality that justifies actions and gives an opportunity to transform, reorganize, and restructure one’s environment (Dubet, 1994). As a network of categories, social representations are an elaboration of an object by a group of people that establishes some modalities for communication and further action (Abric, 1994; Garnier & Rouquette, 2000; Moscovici & Abric, 1984).

Effectively, future teachers’ social representations on race and ethnocentrism are present before their teacher education and remain in their professional activities. Through the reflections written in journals, when each of them expressed her or his opinions, each expressed her or his life story and her or his singular but contextualized voice. As an example, a preservice teacher expressed her sense of her social representation regarding her way of avoiding a racist attitude interacting with students when observing her inner city secondary classroom during her field experience. Then, her social representation could be connected to a collective representation that could be shared with other teachers. In summary, we wanted to understand what the social representations of preservice secondary teachers are when they elaborate their social norms, how they identify their particular system of values to the one of others, and why they justify their practices and actions.

There are several versions of constructivism (i.e., radical constructivism, social constructivism). Although some constructivists believe in intangible mental constructions, others think that there is a reality or a more tangible mental construction based in actions or in written texts. Stanley and Wise (1983) have argued that “the ‘deductivist’ view of science is that theory precedes research,” whereas “the ‘inductivist’ view of science is that theory construction derives from ‘experience’ ” (p. 48). Therefore, our study is embedded in a constructivist inquiry paradigm consisting of those individual reconstructions coalescing around consensus (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). Ontologically, it refers to relativism, which assumes that realities are “multiple, intangible mental constructions, socially and experientially based, local and specific in nature . . . and dependent for their form and content on the individual persons or groups holding the constructions” (p. 111). These constructions can be seen as “created realities” that occur “through the interaction of a constructor with information, contexts, settings, situations, and other constructors (not all of whom may agree), using a process that is rooted in the previous experience, belief systems, values, fears, prejudices, hopes, disappointments, and achievements of the constructor” (Guba & Lincoln, 1989, p. 143).

Constructions happen when the “knower interacts with the already known and the still-knowable or to-be-known” (Guba & Lincoln, 1989, p. 143). Epistemologically, constructivism refers to a subjectivist perspective. The constructor/investigator and the object of construction/investigation are assumed “to be interactively linked so that the ‘findings’ are literally created as the investigation proceeds” (p. 111). Methodologically, it refers to hermeneutical and dialectical analysis. It suggests “individual constructions can be elicited and refined only through interaction between and among investigator and respondents.” These constructions used conventional exploratory techniques “compared and contrasted through a dialectical interchange [ultimately] to distill a consensus construction” (p. 111).

All of the preservice secondary teachers in the study were in their 3rd out of 4 years of training at the university. Their field experience occurred primarily in an urban setting. Most lived in direct proximity to the inner ring suburbs. Approximately two thirds of the students were female, and one third was male. Participants were predominantly White and primarily English speaking. Most of the students were returning students, in the sense that they took a break from their educational careers or from other professions. Twenty-five out of 60 students (40%) in two sections of the course agreed to be participants in the study. The selection of the students was based on their willingness to participate, their capability to express their thoughts, the diversity of their subject matters (mathematics, science, language arts, history, music, plastic arts, social studies, geography), and the settings of their field experiences.

Instrumentation for collecting data is neither external nor objective; rather, it is internal and subjective.

The instrument in naturalistic inquiry is not operational definitions describing variables, but a sensitive homing device that sorts out salient elements and targets in on them. The instrument becomes more refined and knowledgeable in that process. (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p. 224)

According to these principles, the design procedures consisted of four phases. In Phase 1, we aimed to establish a research framework, plan a time line, select participants, and clarify the roles of team members. In Phase 2, the primary researcher proposed the first version of the study design, the conceptual framework, and the method. Then, the two coresearchers validated the study design as well as the conceptual and methodological frameworks. In Phase 3, the first two researchers collected journals. The third phase included collecting data from preservice teachers’ journals about their experiences. In the fourth phase, all three researchers (the two coresearchers and the collaborator) were involved in describing and analyzing data, first independently and then collectively.

These university students kept reflective journals of their experiences observing and teaching in classrooms. The goals of this secondary methods class were to (a) experiment with reflective practice, (b) develop knowledge of best practice, (c) teach models of classroom management and models of teaching and learning, (d) elaborate a personal teaching philosophy, (e) reflect on how they were taught, (f) provide an opportunity to “micro-teach” with their peers with feedback from both peers and the instructor, and (g) give students a place to voice their opinions, ideas, and experiences. The course instructor was responsible for teaching the university class and to observing the students’ fieldwork.

The assignments for the class included (a) developing a personal teaching philosophy; (b) writing a preteaching classroom management plan and unit and lesson planning; (c) making a personal inventory of the students in their placement class (e.g., age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background); (d) keeping a reflective journal of their experiences; (e) connecting planning and practice to national, state, and local standards; (f) teaching one unit at their placement; (g) writing a postteaching management plan; and (h) presenting a professional portfolio. Moreover, readings included a text on creating unit and lesson plans, constructivist theory, questioning theory, and a classroom management text on implementing democratic discipline (Hoover & Kindsvatter, 1997). From these assignments, data collection consisted of gathering and relating preservice teachers’ reflective journals of their experiences.

Students were required to send their journals of no predetermined length to their professor via e-mail. Their journals provided a space for both introspection and outward manifestation of their thoughts. From their social representations of different aspects they observed during their field, we selected many themes from different subject matters in different secondary classes. In terms of principles of ethics, we were very cautious about interference during the semester classes. We collected reflective journals, which were not evaluated, from students during the semester, and we started describing and interpreting data only after we evaluated the students’ required assignments. The students consented to participate in this work. To ensure confidentiality, neither students’ nor mentoring teachers’ names appear in this text. To protect anonymity, all names used are pseudonyms. Moreover, all of the research activities we undertook throughout this project were supervised by the university’s institutional review board (IRB).

Content analysis is a form of empirical qualitative research that generally refers to human existence shown in action in a particular context. Human action emerges through the interactions of a person’s previous learning and experiences, present situated interests, and proposed goals and purposes (Hatch & Wisniewski, 1995). In this study, we report preservice secondary teachers’ reflective journals that refer to the understanding of their social representations. The analysis depends completely on quotes from the participants’ thoughts to support our choice of themes to be examined. Themes emerged from the preservice teachers’ journals either from repeated use, from different participants, or from ways in which the themes are stated that make them seem significant (Deslauriers, 1991; L’Écuyer, 1988). These similarities are influenced by the cultural context of the students’ experiences, both inside and outside of the university classroom. We also examined the differences among students when they described their personal and professional experiences and represented themselves within their respective sociocultural milieu. Then we made sense of classified provisory data, and analyzed it from a particular to a more general category.

In the context of naturalistic and constructivist inquiry, data analysis is rather open ended. Because the product of data cannot be known in advance, “the data cannot be specified at the beginning of the inquiry” (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p. 224). The strategy of inquiry will be to make a sound meaning of the data to “facilitate the continuing unfolding of the inquiry [and] understand the phenomenon in its context” (p. 225). Data-analytic procedures are a relevant technique for providing conclusive and significant findings, because they should be able to answer the questions posed. Data analysis was founded in a content analysis approach. Each component of data analysis was dependent on the characteristics of all preceding elements and their development. Morse (1994) stipulated this:

As the study progresses, theoretical insights and linkages between categories increase, making the process exciting as “what is going on” finally becomes clearer and more obvious. Data collection and sampling are dictated by and become directed entirely toward the emergent model. The researcher seeks indices of saturation, such as repetition in the information obtained and confirmation of previously collected data. Using theoretical sampling, the researcher looks for negative cases to enrich the emergent model and to explain all variations and diverse patterns. (p. 230)

In this study, we researchers first analyzed the data independently. Then, we compared and contrasted our individual analyses collectively to reach to a consensus. This procedure for a collective construction was a form of triangulation among researchers (McCracken, 1988). Based on the emerging pattern construction, several themes were developed. We discussed these themes in what follows.

From the conceptual framework, we define to some extent what were the preservice secondary teachers’ representations in terms of the tripartite multi- and intercultural education (traditional, liberal, and critical-radical) regarding race and ethnocentrism, and how these future teachers reacted to it. In this section, we examine the voices of Paul, Jenny, Helen, Maria, Brian, and Elizabeth (pseudonyms).

Paul seems very aware regarding material content that provides unbiased cultural diversity to students and is free from stereotypes and prejudices.

In terms of dealing with race, ethnicity, gender, religion, and socioeconomic status of students, the teacher must take care in choosing reading material that speaks to a variety of types of people [without folklorizing, trivializing, barbarizing, prejudging or stereotyping]. This has been addressed in the anthologies of the time. The teacher must back this up by modeling an unbiased attitude toward human beings, and by having an unbiased attitude while looking at student writing. (Paul)

To understand Paul’s statement, we have to look more closely at stereotypes and prejudices that contribute to the elaboration of social norms.

Paul applies, in the context of his classroom, an ideal state of societal conditions characterized by tolerance, equity, and mutual respect within this existing cultural classroom. This position contrasts keenly with cultural assimilation, or the melting pot model, whereby immigrants are expected to abandon their traditions and accept being absorbed or acculturated by the predominant culture. Consequently, Paul promotes an education that is multicultural by accepting cultural pluralism. Through his impartial attitudes, he is concerned about selecting sound reading material for diverse students. Such a pedagogical approach provides students with a reflection about relation and interdependency. It shows to them the importance of recognizing human realizations and the interactions that occur within a culture and among cultures.

In this section, we will hear the voices of three teachers: Jenny, Helen, and Maria. First, Jenny describes her struggle when she was learning English at preschool. Her story shows how a traditional perspective in multicultural education that does not consider the value of her native language and her ethnic background affected her school experience. Here, she expresses her difficulties in learning English.

During my early education the school system that I attended did not have any kind of bilingual or ESL programs. I was basically “immersed” into the classroom. It was either sink or swim. Fortunately, I had a very understanding kindergarten teacher. She knew my struggle because she had the same experience and difficulty. She spoke slowly and took some extra time explaining things to me. Looking back at my experience gives me a better understanding about the struggles that many immigrant children have today. I can empathize with their struggle. Because of my experience of learning English as a second language, I feel that I am better equipped to handle such situations in my future classrooms than many other teachers. To have a bilingual student in my classroom would be a challenge, but also rewarding. Making the transition from one language to another can be very confusing. Because of this, the child could become very withdrawn and have low self-esteem. This makes the child feel that he/she is not intelligent enough to understand their subjects. That is why I feel it is very important to let the child feel that he/she is part of the classroom and not alienated from the rest of the class. (Jenny)

Jenny had already experienced bilingual education when she was “immersed” into the classroom. Although the native language can interfere with learning English, Jenny still remembers the sensitivity and support her kindergarten teacher provided her. Through her reflection, she is able to analyze her advantage, comparing it to other teachers who had not experienced it. She favors an effective cultural pluralism in her interactions with students. In this example, it is obvious that the role of a caring and sensitive teacher to diversity is crucial and can make a significant and positive difference in the life of a child. She believes in the responsibility of a teacher to promote democratic and equitable values in the classroom environment. Her relativist perspective focuses on the equality of cultures, showing the limits of an ethnocentric perspective that considers the mainstream in a central position. Jenny is a liberal and empathic teacher working in a traditional multicultural environment that is assimilationist.

Helen, another teacher, pushes this idea further when she realizes the paradox between the inference of a native language on learning English and the benefits of learning and knowing a second language.

Growing up in today’s multicultural and racially diverse American society can be very stimulating and interesting. Teachers today have to become culturally knowledgeable about the many cultures, languages, races, religions, socioeconomic statuses and even learning styles and intelligences in their classrooms. This can be a very difficult and time-consuming job, but very beneficial in the end. Growing up in a bilingual household has many advantages as well as disadvantages. Knowing a second language, I believe, is very beneficial to everyone. (Helen)

She is involved in establishing congruence between what happens to students in a classroom and their sociocultural values and backgrounds. Like many other preservice teachers, Helen shows that she recognizes the difficulties of teaching in an appropriate manner and is concerned about teaching conditions. She expresses here the importance for preservice teachers of being conscious of and sensitive to diversity. It is also important for her to recognize differences on an equal footing. From her perspective, the role of the teacher is to help students demystify the variety of attitudes, beliefs, and customs.

There is no doubt about the need when learning a foreign language to demystify the notion of ethnocentric biases, which refers to the ways in which we look at the world from our perspective or from our own filter of meaning or understanding. In this sense, Helen understands the importance of decentralization from her perspective and the students’ perspectives for her to be able to understand her students. She has the intuition of intercultural dynamics, because she is able to encourage her students “to see other cultures as equally good, and not strange,” and she uses this experience to invite her students to look at themselves, at their own cultures, through the eyes of others, succinctly, toward multicultural education that promotes mutual respect. In fact, Helen is a culturally enthused teacher concerned about a multicultural education that is pluralist.

The third teacher is Maria, an English language future teacher. She is conscious of teaching “facility in the dominant language,” and although “many students . . . are not using English in their homes as their first language,” they have to use “standard English.” As we can see, her expectations that target all students are very high, because she knows that “English is still considered a yardstick for measuring education” and for providing job opportunities.

The concept behind the subject [English] is to teach facility in the dominant language . . . many students in [such area] are not using English in their homes as their first language, or they are not using standard English. Nonetheless, it is clear to me that the students are best served by a language arts teacher who expects the use of standard English, and who expects the most advanced use of standard English that is possible for any given student . . . the proper use of English is still considered a yardstick for measuring education. Thus, the job of the language arts instructor is to bring students into their best possible light in the workforce—that is, as a competent speaker and writer of standard English. (Maria)

At first sight, Maria’s opinions seem very conventional in embracing an assimilationist perspective, because she wants her students to master English, the dominant language. In fact, her desire is to offer the most advanced use of standard English that is possible for all students. From our understanding, Maria seems to favor an education that is social reconstructionist and points out the necessity of promoting social structural equality. Through her representations, Maria is engaged socially and actively in targeting issues of equal access to educational resources. After this analysis, this liberal perspective toward intercultural education is a position that can be defended only by a reflective teacher.

Briefly, Jenny teaches in a multicultural environment that is assimilationist. However, her caring teacher provided a role model for her in developing a multicultural capability to support a student learning a foreign language. Helen, a culturally enthused teacher, is concerned about a multicultural education that is pluralist. She recognizes differences but also encourages diversity. She believes that all cultures should be promoted with mutual respect and treated as equally good. Although Maria recognized and respected diversity, she sees the necessity of promoting social structural equality, because an immigrant needs to master the dominant language to be engaged successfully in the process of social and economic integration. All of these teachers consider differences as a resource, not as a problem.

Brian’s social representations illustrate his sense of sociocultural responsibility. Although university students need to develop their knowledge in terms of multi- and intercultural education, many of them, including Brian, have a sense of the importance of having a broader understanding of the role of the teacher and the impact of the society on the school.

In today’s society, children tend to be diverse not only by race or ethnicity but also by the cliques they belong to. They have different expectations and personal problems that vary from wanting to be a pharmacist to being a drug abuser. So my question is how do we recognize their problem and how do we keep them focused on school? I believe the over the year, as schools grow larger and it becomes harder to be familiar with all the students in the school, teacher will lose the important role of being there for students in their time of need. I think schools play an important part of students’ social lives. As a result, along with academic learning, lessons in moral behavior and rational decision makers should be part of the school learning experience. Most important, teachers should pose as role models for students and be there for them because sometimes they don’t have anywhere else to turn to. (Brian)

Here, Brian proposes a shift from a knowledge-centered to a student-centered perspective. We agree with those authors and teachers who value the development in learning skills for becoming critical, conscious, and socially active citizens. Another focus is the establishing of congruence between what happens inside and outside of the schools, as critical multi- and interculturalists suggest.

In the following episode, Elizabeth describes a Black female student who spoke out because she felt that she was racially discriminated against by an inflexible White male teacher. This is a situation that a teacher should be ready to deal with.

A black female student “N,” who often received B’s and consistently completed her assignments, looked down at her homework grade and, in a serious tone, commented to the [White male] teacher, “Look here, we’re goin’ to have a serious talk about this . . . you don’t seem to understand, I do my homework. I answer all the questions—and you can never mark them all right!” Acting disgusted, she turned away from the teacher and opened her notebook. Correct answers were reviewed with the students, during which they loudly challenged the teacher’s answers, calling out, “That’s what I put down . . . that’s so stupid . . . you always mark my paper wrong!” [The teacher], in a stern voice, loudly cautioned the class to settle down or he would send them all to the Assistant Principal’s office. (Elizabeth)

A racist attitude is not only a network of beliefs and convictions. It is also related to behaviors, practices, and actions. There are still teachers who think that Black students are slow learners, poor achievers, potential dropouts, and academic failures. In this episode, the student complains about her feeling of being discriminated against. She said she “often received B’s,” although she “consistently completed her assignments.” She invites her teacher to have “a serious talk about this.” She reminded the teacher, “you don’t seem to understand [that] I do my homework. I answer all the questions—and you can never mark them all right!” This student reminds us of the necessity of analyzing the mechanisms of racist attitudes we all integrated, often without further considerations and self-reflection. Such teacher-student interactions happen every day, many times a day in thousands of classrooms in the United States and elsewhere. Teachers should be engaged in the transformation of the society and of the school in rejecting racism. The preservice teacher who related this episode was particularly affected by this situation. The process of becoming multi- and interculturally competent includes the exploration of alternative ways of communicating that engage the teacher and his or her students for a democratic, equitable, and inclusive classroom.

Preservice teachers expressed their sense of social representation regarding their ways of understanding, reflecting, and coping with diversity when they were observing a teacher and students in an inner city secondary classroom during their field experience. Their social representations were not static but, rather, dynamic. They were connected to a collective representation that they mainly shared with other teachers. If we try to define their social representations on racism and ethnocentrism, we can confidently say that most of them valued a liberal perspective, although they related some situations that revealed a traditional context. The characteristics of the milieu they described suggested an education that was assimilationist, essentialist, relativist, unbiased ethnocentric, tolerant, respectful, pluralist, and antiracist. For that matter, these categories referring to traditional, liberal, and critical multi- and intercultural education overlapped. Supported by their attitudes, teachers were genuinely caring, empathic, communicative, culturally enthused, socially reflective, impartial, and responsible. They favored integration of different subject matters.

As we mentioned earlier, the process of becoming a multi- and interculturally competent teacher requires a reflection on definitions that were taken for granted. For example, although much research on DNA points out the inappropriateness of using the term race, even culturally and socially sensitive preservice teachers writing their narrative journals never requestioned this concept and its consequence of categorizing peoples. They never seriously considered other options or analyzed critically stereotypes, prejudices, discrimination, racist attitudes, and ethnocentric biases toward propulsion of transformative actions. They continue to use the term every day when they are referring to textbooks, preparing their lesson plans, or interacting with students. Consequently, preservice teachers need to become more aware about the significance of racism and of ethnocentrism and its impact on the lives of their students. They often generalize their own perspective without realizing that their worldviews are culturally and socially founded. When something seems universal, they have to ask themselves, for whom is it universal? A better understanding of culture and experiences in multi- and intercultural education is needed to adequately prepare preservice teachers for teaching in a highly pluralistic society.

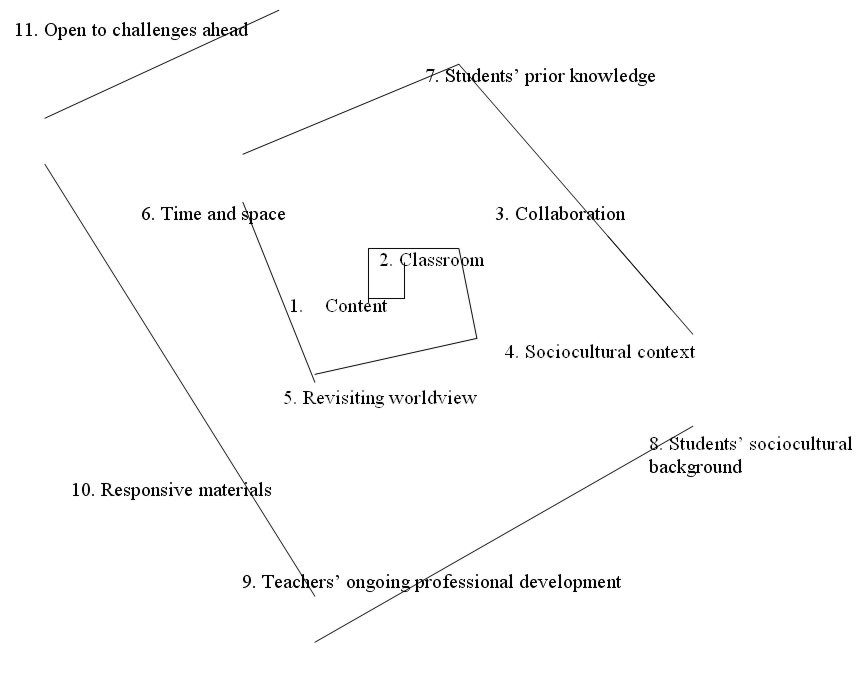

As reported above by Tellez and colleagues (1995), teachers are educated mainly in the middle class and come from White communities, and they estimate that by the year 2020, almost one third of the school-age population will be non-White, and almost one fourth will live in economic poverty, of whom more than half will be White. Facing this reality, many challenges are ahead. A holistic approach might enhance the process of becoming a multi- and interculturally competent teacher. Imagine a spiral that represents the interactions between the teacher and students when they are teaching and learning in the context of a classroom.1

Figure 2. Intercultural education spiral model

The first preoccupation of a teacher is what she or he actually has to teach: the content. It is what a teacher experiences as a student as well as the way in which she or he has been educated in a college or university. Associated with the content of a subject matter, a teacher learns to focus on the pedagogical content knowledge. This is the substance and the form (Adler, 2001) (Figure 2, No. 1). Both content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge are social construction connected to the context of the classroom.

The first preoccupation of a teacher is what she or he actually has to teach: the content. It is what a teacher experiences as a student as well as the way in which she or he has been educated in a college or university. Associated with the content of a subject matter, a teacher learns to focus on the pedagogical content knowledge. This is the substance and the form (Adler, 2001) (Figure 2, No. 1). Both content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge are social construction connected to the context of the classroom.

In the era of information and accountability, this model is supported by the idea of togetherness. If we want to learn to live together in the context of the classroom and of the society, we can learn with our students how to process a task collaboratively (Figure 2, No. 2). Working collaboratively favors the integration of any themes within a subject matter. For example, teachers can explore with their students, within the domain of mathematics, what, how, and why to connect number patterns with algebra, geometry, measurements, and data collection. In addition, they can connect mathematics with other subject matters such as science and literacy as well as arts and music (Figure 2, No. 3), which are not acultural, asocial, ahistorical, or apolitical.

Moreover, in this study, participants’ social representations remind us of the importance of the context (Figure 2, No. 4). Here, sociocultural aspects of the context refer to the content, the classroom, and the collaborative interactions. The challenges of a more democratic and inclusive society, as Larkin and Sleeter (1995) have proposed, invite us to reflect on establishing a sound multi- and intercultural teacher education curriculum. They also challenged the narrow dominant sociocultural perspective of most of the students’ education in reflecting on the impact of racist (Pollock, 2001; Taguieff, 1997) and ethnocentric worldviews (Arcand & Vincent, 1981; McAndrew, 1986; Preiswerk & Perrot, 1975) (Figure 2, No. 5). These statements refer to revisiting racism and ethnocentrism regarding all aspects of educational strategies within any subject matter. Ollivier (1988) suggested the inclusion of time (the recognition of the past, present, and future of human realization) and space (related to interactions that occur within a culture or among cultures) at any moment during the process of contextualizing teaching and learning (Figure 2, No. 6).

Opening up the intercultural spiral, the researchers and preservice teachers recognized the importance of the students’ prior knowledge (Figure 2, No. 7) and the sociocultural background of all students (No. 8). Curricular issues are part of a broader agenda that must be addressed by teacher education programs whose administrators are willing to face the challenges of diversity and equity. Three other aspects have to be considered as well: constantly upgraded and transformed components of an ongoing professional development (No. 9), creation of culturally responsive materials (No. 10), and openness that allows all educators to explore and ask “what . . . if” questions. These aspects are critically important for a transformative education in an open society (No. 11).

In creating this spiral and its components, we are inspired with the proportion of Fibonacci sequence: a series of numbers, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21 . . . , in which each successive number is equal to the sum of the two preceding numbers. The spiral here is the representation of an open-up model, an ongoing and emerging learning that shifts from content to context as well as from a teacher-centered to a students-centered perspective. This transformation toward an epistemology consists of shifting away from a technicist perspective to a constructivist and creative approach. From our reflection, if one really wants to reach these goals, schools should

recruit aggressively preservice teachers of color and others with cross-cultural life experience and a positive orientation to working in culturally diverse settings.

Likewise,

if programs are to equip new teachers realistically to work in urban, multicultural settings, it seems clear to us that the focus of that preparation will need to shift away from the isolation of the campus toward greater interaction and collaboration with the schools and other agencies which know and serve urban communities. (Larkin & Sleeter, 1995, p. viii)

These challenges of cultural diversity and equal opportunity should invite all of us to reflect on avoiding a narrow dominant culture perspective and establishing a sound multi- and intercultural teacher education curriculum.

1. Nicole Carignan and Roland Pourdavood (who was USA Fulbright Grantee 2004) developed this model in the framework of their research at University of Port Elizabeth (UPE), currently known as Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU), Department of Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education (SMATE), at Port Elizabeth in South Africa. Back to text

Abric, J. C. (1994). Les représentations sociales: Aspects théoriques. In J. C. Abric (Ed.), Pratiques sociales et représentations (pp. 11-35). Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Adler, J. (2001). Teaching mathematics in multilingual classrooms. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer. rt, G. (1979). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Arcand, B., & Vincent, S. (1981). L’image de l’Amérindien dans les manuels scolaires du Québec. Lasalle, Canada: Hurtubise.

Banks, J. A. (1999). Introduction to multicultural education. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Bennett, C. I. (1999). Comprehensive multicultural education, theory and practice. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1970). La reproduction. Paris: Édition de Minuit.

Camilleri, C., & Cohen-Emerique, M. (1989). Chocs des cultures: Concepts et enjeux pratiques de l’interculturel. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Carignan, N. (1996). Éducation musicale et éducation interculturelle: La représentation du musicien. Les Cahiers de l’ARMuQ, 18, 43-58.

Deslauriers, J. P. (1991). Recherche qualitative, guide pratique. Montréal, Canada: McGraw-Hill, Thema.

Doise, W. (1990). Les représentations sociales. Traité de psychologie cognitive, 3(Dunod), 111-174.

Dubet, F. (1994). Sociologie de l’expérience, Paris: Seuil. Collection “La couleur des idées.”

Exama, A. (2005). Jusqu’où va la différence? La hiérarchie des races, l’erreur de Socrate. Lévis, Canada: Les Éditions de la Francophonie.

Garnier, C., & Rouquette, M.-L. (2000). Représentations sociales et éducation. Montréal, Canada: Éditions nouvelles.

Ghaffari, M. (2000). Intelligence: E pluribus unum, an ontological and epistemological inquiry. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH.

Grant, C. A. (1978). Education that is multicultural—Isn’t that what we mean? Journal of Teacher Education, 29, 45-49.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.)., Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105-117). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hannoun, H. (1987). Les ghettos de l’école: Pour une éducation interculturelle. Paris: Édition ESF.

Hatch, A., & Wisniewski, R. (Ed.). (1995). Life history and narrative. London: Falmer.

Hoffman, D. F. (1996). Culture and self in multicultural education: Reflections on discourse, text, and practice. American Educational Research Journal, 3(3), 545-569.

Hoover, R., & Kindsvatter, R. (1997). Democratic discipline: Foundation and practice. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Jodelet, D. (1991). Les représentations sociales. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Lal, S. (2004). 1930’s multiculturalism: Rachel Davis DuBois and the Bureau for Intercultural Education. Radical Teacher: A Socialist, Feminist and Anti-Racist Journal of the Theory and Practice of Teaching, 69, 18-22.

Larkin, J. M., & Sleeter, C. E. (1995). Developing multicultural teacher education curricula. New York: State University of New York Press.

L’Écuyer, R. (1988). L’analyse de contenu: Notion et étapes. In J. P. Deslauriers (Ed.), Les méthodes de la recherche qualitative (pp. 9-65), Québec: PUQ.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Linn, R. (1996). A teacher’s introduction to postmodernism. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Martin Sanchez, M.-O. (2000). Concept de représentation sociale. Retrieved August 20, 2004, from http://www.serpsy.org/formation_debat/marieodile_5.html

McAndrew, M. (1986). Études sur l’ethnocentrisme dans les manuels scolaires de langue française au Québec. Montréal, Canada: Les Publications de la Faculté des sciences de l’éducation, Université de Montréal.

McCarthy, C. (1994). Multicultural discourses and curriculum reform: A critical perspective. Educational Theory, 44(4), 81-99.

McCracken, G. (1988). The long interview. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

McLaren, P. (1995). Critical pedagogy and predatory culture: Oppositional politics in a postmodern age. New York: Routledge.

Morse, J. M. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 220-235). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Moscovici, S. (Ed.) & Abric, J. C. (1984). La psychologie sociale. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Moussa, S. (2003). L’idée de “race” dans les sciences humaines et la littérature (XVIIIe et XIXe siècles): Histoire des sciences humaines. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Ollivier, É. (1988) Stratégies paradoxales des migrants et dimensions paradoxales de l’éducation interculturelle. In F. Ouellet (Ed.), Pluralisme et école: Jalons pour une approche critique de la formation interculturelle des éducateurs (pp. 85-106). Saint-Laurent, Canada: Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture.

Ouellet, F. (1991). L’éducation interculturelle: Essai sur le contenu de la formation des maîtres. Paris: Éditions L’Harmattan.

Pollock, M. (2001). How the question we ask most about race in education is the very question we most suppress. Educational Researcher, 30(9), 2-12.

Preiswerk, R., & Perrot, D. (1975). Ethnocentrisme et histoire: L’Afrique, l’Amérique indienne et l’Asie dans les manuels occidentaux. Paris: Anthropos.

Sanders, M., & Carignan, N. (2003). Self- and sociocultural representations of future teachers. Teaching & Learning: The Journal of Natural Inquiry and Reflective Practice, 17(2), 86-100.

Sleeter, C. E., & Grant, C. A. (1994). Making choices for multicultural education: Five approaches to race, class, and gender. New York: Macmillan.

Stanley, L., & Wise, S. (1983). Breading out: Feminist consciousness and feminist research. London: Routledge and Kegan.

Taguieff, P.-A. (1997). Vers un modèle d’intelligibilité. In P.-A. Taguieff, Le racisme (pp. 57-71). Paris: Flammarion.

Tellez, K., Hlebowitsh, P. S., Cohen, M., & Norwood, P. (1995). Social service field experiences and teacher education. In J. M. Larkin & C. E. Sleeter (Ed.), Developing multicultural teacher education curricula (pp. 65-78). New York: State University of New York Press.

| International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (3) September 2005 |