| International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (1) March 2005 |

Pieced together: Collage as an artist’s method for interdisciplinary research

Kathleen Vaughan

Kathleen Vaughan, BA, AOCA, MFA, is a visual artist, teacher, writer, and doctoral candidate in education at York University, Toronto, Canada

Abstract: As a visual artist undertaking doctoral studies in education, the author required a research method that integrated her studio practice into her research process, giving equal weight to the visual and the linguistic. Her process of finding such a method is outlined in this article, which touches on arts-based research and practice-led research, and her ultimate approach of choice, collage. Collage, a versatile art form that accommodates multiple texts and visuals in a single work, has been proposed as a model for a “borderlands epistemology”: one that values multiple distinctive understandings and that deliberately incorporates nondominant modes of knowing, such as visual arts. As such, collage is particularly suited to a feminist, postmodern, postcolonial inquiry. This article offers a preliminary theorizing of collage as a method and is illustrated with images from the author’s research/visual practice.

Keywords: aesthetic practice, artistic practice, textile sculpture, interdisciplinary

Citation

Vaughan, K. (2004). Pieced together: Collage as an artist’s method for interdisciplinary research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(1), Article 3. Retrieved [insert date] from http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/4_1/html/vaughan.htm

Author’s Note

I thank Rishma Dunlop, Warren Crichlow, and Don Dippo for their contributions to this article, as well as the three anonymous reviewers whose thorough and helpful comments provoked considerable reworking of and improvements to this piece. I can be contacted at www.akaredhanded.com

Introduction

Why should any fully engaged artist worthy of the name, of whatever age, wish to return to university or art college in order to spend six years studying for a “practice-based” PhD? Why, exactly, would they want to do that? (Thompson, 2000, p. 35)

The phrasing of these questions, raised at a recent U.K. symposium about research and the artist, suggests irreconcilability between artistic practice and scholarly research, an unfathomable strangeness in a practicing artist’s wish to pursue higher education. As a visual artist and doctoral candidate in the Faculty of Education at York University, I see no contradiction between these endeavors. In fact, I have come to see them as interwoven and mutually sustaining. My efforts to find an appropriate working method for my inquiries have helped me to knit art and research together.

The method I have come to is collage—a fine arts practice with a postmodern epistemology. In this essay, I use theory and practice to situate a collage method within the current experimental moment in the human sciences (Marcus & Fisher, 1999) and suggest that it might reflect a borderlands epistemology (Harding, 1996)—one based in an inclusive, liberatory agenda that can work in the overlappings of multiple disciplines.

In the first section of my article, I describe key concepts from two recognized approaches to research in and through the arts: arts-based research and practice-led research. I also propose collage as a related research practice and identify the epistemological underpinnings that make this form of art making adaptable to knowledge practices. Then in the second section, I move to practice, and to a discussion of my current work of research and artistry, the Unwearable series of textile sculptures. Here, images and reflection trace my progress and bring transparency to my artistic practice. In the third section, on integrating theory and practice, I build from this work to propose nine qualities of a collage method. Finally, I offer a conclusion.

I wrote this essay in response to the recent call (from Piantanida, McMahon, & Garman, 2003) for arts-based scholars to identify the epistemological and ontological underpinnings of their work so that we can deepen our conversations. I am also hoping that my discussion of the U.K.-based method known as practice-led research—not, to my knowledge, addressed in recent North American literature—might be of interest and use to scholars and artists on this continent. By including numerous images, I aim to provoke within the reader, the viewer, an attunement to the visual, encouraging both a sensuous scholarship (Stoller, 1997) that resides in aesthetic and research practices and a good-natured assault on the lingering verbal biases of the “logocratic academy” (Taylor, 1994, p. xii). Similarly, I hope the integration of theory into my practice will challenge antischolastic biases within the art world and address Thompson’s (2000) question, above, for, indeed, there are many good reasons for an artist to undertake a PhD.

Theory

Three years ago, my research and creative practices were sparked by one particular artifact: my father’s childhood photograph album, seen by me for the first time 15 years after he had died.

The image in Figure 1 portrays this compilation, a recognizably typical album with black leather cover and dog-eared black blotting paper pages.1 This one contains 277 photographs and consists of a book-based work of juxtapositions—an assembled order of images and captions from 1916 through about 1956.

Figure 1: Photograph album

At the start of my doctoral work, I did not know how I would make use of this album in my creative practice, but I knew it would involve mixed media and would probably end up being a version of a collage in its own right. As well, I knew that my hands-on creation would be interwoven with and affected by my concurrent text-based researches.

In this work, I aimed to explore large issues: What does art know? and, second, What would be an appropriate methodology or method2 for exploring this question and representing my explorations? What is a methodology? As I describe it here, a methodology is less a “plan of action” (Crotty, 1998, p. 3) than a “logic of justification” (J. K. Smith & Heshusius, 1986), an “elaboration of logical issues and . . . the justifications that inform practice” (p. 8).

When I started on my doctoral journey, the permutations and manifestations of qualitative research methodologies were completely fresh to me. As a practicing artist with a master’s degree in fine arts (MFA), my training came from other traditions. Believing that art is a way of knowing (Eisner, 2002), I looked for connections between art making and research, and I found many. For instance, Denzin and Lincoln (2000) described qualitative research in terms of three creative forms: bricolage,3 montage, and quilt making (pp. 4-5). Artist Davis and education scholar Butler-Kisber (1999) together have explored the practice and principles of collage as a means of enriching educational research.4 Even more fundamentally, Finley and Knowles (1995) drew equivalences between the two practices in their joint article “Researcher as artist/Artist as researcher.” Similarly, Watrin (1999) has considered art to be a kind of research. Many of these scholars refer to or engage in arts-based research, the social sciences methodology that best describes my work.

Arts-based research

In a seminal article on the topic, arts-based research is defined by Eisner and Barone (1988/1997) as follows:

the presence of certain aesthetic qualities or design elements that infuse the inquiry and its writing. Although these aesthetic elements are in evidence to some degree in all educational research activity, the more pronounced they are, the more the research may be characterized as arts based. (p. 73)

Eisner and Barone (1997) also identified seven features that infuse arts-based research: the creation of a virtual reality, the presence of ambiguity, the use of expressive language, the use of contextualized and vernacular language, the promotion of empathy, the personal signature of the researcher, and the presence of aesthetic form.5 I believe that these features are embodied in my creative work, perhaps because most are defining characteristics of contemporary artwork.

Supporters and practitioners of arts-based research tend to recognize the value of alternative modes of representation and suggest these as a postmodern (Eisner, 1997), feminist (Finley, 2001), or postcolonial (Dimitriadis & McCarthy, 2001) countering of a Western positivist paradigm. Characteristic of recent arts-based research is a cultural politics that is critical, that aims to provoke action and change, for which the artist/researcher takes on an activist role (Mullen, 2003).

In the past decade, there has been an explosion of arts-based research, experimentation that has resulted in hybrid forms of all kinds of arts practice (Mullen, 2003). Arts-based research can span a broad spectrum of activities, from research for which the arts are a form of data representation to research that is generated as art is created.6

In their recent overview of trends in arts-based research, Piantanida et al. (2003) have proposed “at least five conversational moments” (pp. 187-188), interwoven and not necessarily mutually exclusive, that reflect categories of researchers’ interests in art. Researchers might focus on art as a mode of persuasion (particularly within the political arena), as a mode of self-exploration, as a mode of pedagogy (with links to art education), as a mode of representing knowledge, and/or as a mode of constructing/generating knowledge (p. 188). Within this latter category are, they have proposed, “individuals interested in discussing epistemological, ontological, axiological and methodological intricacies of claiming a study as arts-based” (p. 189). It is here that I place myself as well as most proponents of practice-led research.

Practice-led research

Practice-led research is, in the words of Gray (1996), one of the pioneers of this field, “research initiated in practice and carried out through practice” (p. 1). By practice, she and other theorists mean artistic practice.7

In fact, so far most of this work has been done within fine arts departments of British universities,8 where researchers borrow theories and methods from other disciplines: constructivist theory from the social sciences and complexity theory from the sciences (Gray & Malins, 1993). The United Kingdom is now into its fourth generation of practice-based researchers, who work in sculpture, ceramics, musical instrument design, environmental art, and so on (Gray, 1996). Their work is supported by a broad-based, nation-wide framework established by the Arts and Humanities Research Board (AHRB), which provides a governing definition of research based in practice and manages a national Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) that documents and funds faculty research in postsecondary institutions.

Canada, too, is working to legitimize a culture of research/creation through the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), specifically the 5-year pilot program of research/creation grants in fine arts for artists who work as faculty in universities or colleges. This program was created to address the potentially transformative nature of research undertaken by artist-researchers and the centrality of creative practices to current interdisciplinary research. SSHRC (2003) has defined research/creation as

any kind of research activity or approach to research that fosters the creation of literary or artistic artworks of any kind, where both the research and the works it fosters meet standards of excellence and are suitable for publication, public performance or viewing. (p. 3)9

More specifically, a proposed project must represent a new development, be original and innovative, or renew some aspect of the field of artistic expression (SSHRC, 2003, p. 3). Clearly, the expectation is that the work of research/creation achieve the highest levels of professionalism.

Neither the SSHRC (2003) guidelines nor the available texts of practice-led research suggest a simple recipe or list of procedures. Rather, practice-led research seems to work heuristically, back and forth between creation and analysis (see Gray, 1995; Gray & Pyrie, 1995).

Similarly to arts-based research, practice-led research is described as having an orientation that is “predominantly post-modernist,” “acknowledging non-linearity, dynamic systems, change, uncertainty” with adherences to constructivist paradigms (Gray & Pyrie, 1995, p. 16). Douglas (2000) has proposed that the purpose ascribed to practice-led research depends on which of three categories an artist/researcher’s work fits. Personal research is motivated by the desire to explore and carry out a professionally based project or product, with the researcher addressing first him- or herself and then interested audience members. Research as critical practice challenges the profession to adopt fresh approaches to creativity, those that are critical and experimental in nature. Finally, formal research in the practice of fine art addresses issues of professionalism: sector-specific training and professional development. I have also noticed that some practice-led research projects seem to address issues that are based in a transformative, inclusive agenda, such as the creation of an environmentally safe, emission-free “clean kiln” and the argument for taking nonverbal skills (the visual artist’s, for example) into consideration in the design and use of new technologies (see Gray & Pyrie, 1995; van der Lem, 2001). However, the more explicitly critical orientation attributed to current qualitative research in the social sciences seems less evident in practice-led research. This is not, however, the case for collage.

Collage

Although collage might be most familiar as a fine arts practice, its epistemological underpinnings suggest its potential as a method for liberatory research in and through the arts. I will explain by briefly discussing collage’s fine art antecedents as well as current philosophical theorizing.

According to the strictest of fine arts definitions, collage comes from the French meaning a glued work. Its origin within Western art is attributed to Picasso and Braque, to artworks from 1911 and 1912 that incorporated newspaper and pieces of chair caning into still life representations (see Poggi, 1992, especially Chapter 1). Reflecting on these origins of collage, Picasso later commented that he and Braque had been seeking a form of representation that enabled in the viewer a trompe l’esprit—a kind of ontological strangeness—instead of the more familiar, painterly trompe l’oeil. As Picasso expressed it, in collage the

displaced object has entered a universe for which it was not made and where it retains, in a measure, its strangeness. And this strangeness was what we wanted to make people think about because we were quite aware that the world was becoming very strange and not exactly reassuring. (cited in Brockelman, 2001, pp. 117-118)

Here are the foundations of a critical practice, inchoate.

Since those early beginnings, collage has been adapted by all kinds of artists, working in two and three dimensions as well as in time-based media such as film, video, and digital processes, with varying degrees of cultural critique (Green, 2000; Hoffman, 1989; Levin, 1989). Like art makers, scholars in fine arts regularly revisit the collage form. In 1989, theorist Ulmer described collage as inherently a knowledge practice and wondered,

Will the collage/montage revolution in representation be admitted into the academic essay, into the discourse of knowledge, replacing the “realist” criticism based on the notions of “truth” as correspondent? (p. 387)

In the intervening 15 years, scholars have created work that answers Ulmer’s (1989) question in the affirmative. For instance, Lather’s “Creating a Multilayered Text: Women, AIDS, and Angels” (1997) and Tanaka’s “Pico College” (1997) are collaged research texts, presenting multiple narratives in a visually conscious design. As well, the members my York University community of artist/scholars—notably Dunlop, Barnett, and I—create collaborative and individual collage-based performative conference texts and publications (e.g., Dunlop, Vaughan, & Barnett, 2003).

My endeavors in this direction are assisted by the extensive work of Brockelman (2001) linking collage to a postmodern knowledge system rooted in paradox. His description of the epistemic contradictions of collage is central to my thinking:

Collage practices—the gathering of materials from different worlds into a single composition demanding a geometrically multiplying double reading of each element—call attention to the irreducible heterogeneity of the “postmodern condition.” But, insofar as it does bind these elements, as elements, within a kind of unifying field . . . the practice of collage also resists the romanticism of pure difference. . . . Collage depends upon a new kind of relationship between these two shards of the traditional concept of worldhood—and, as a result, it promises a new sense of truth and experience, potentially revolutionizing both epistemology and aesthetics. (pp. 10-11, emphasis in original)

A similar observation was made by feminist philosopher Harding (1996), who proposed collage as a model for a “borderlands epistemology” (p. 22): one that values multiple distinctive understandings generated by different cultures and that deliberately incorporates nondominant modes of knowing and knowledge systems. In this way, collage can be used as—in Harding’s view—a postcolonial strategy for broadening the scope of Western knowledges.

With its juxtapositions and overlappings, collage seems very close to métissage10—a kind of braiding or mixing together—which, as elaborated by theorist Lionnet (1989), can also be a decolonizing practice. Lionnet wrote,

We have to articulate new visions of ourselves, new concepts that allow us to think otherwise, to bypass the ancient symmetries and dichotomies that have governed the ground and the very condition of possibility of thought, of “clarity,” in all Western philosophy. Métissage is such a concept and a practice: it is the site of undecidability and indeterminacy, where solidarity becomes the fundamental principle of political action against hegemonic languages. (p. 6, italics in original)

As a Francophone Mauritian, Lionnet considered hegemonic the European languages, particularly written and spoken versions of English and French, whose use in colonized cultures tended to exclude local, primarily oral, Creole languages. As a visual artist, I consider hegemonic languages to be those word-based forms that—in the academy, specifically in social sciences and humanities—tend to crowd out visual and embodied modes of representation. I should be explicit that I do not want to abandon written language: I love it. But I do want to add visual and embodied forms to the mix of representations. Text plus the visual plus the haptic: in other words, a classic collage and, perhaps, a métissage as well.

Brockelman (2001), Harding (1996) and Lionnet (1989) see collage as I do: framed within an attitude of critique that proposes a provisional, postcolonial view of our worlds and the representations we offer of them. Collage also seems to invoke an interdisciplinarity, in its juxtapositions representing “the intersection of multiple discourses” (Brockelman, 2001, p. 2). Thus, collage—with its overlappings, juxtapositions, and shifting centers and margins—can be seen as a transborder practice with epistemological implications: “The borders here are not really fixed. Our minds must be as ready to move as capital is, to trace its paths and to imagine alternative destinations” (Mohanty, 2003, p. 251).

The following discussion of my hands-on art making and related research aims to particularize and embody my work toward a collage method.

Practice

I began by looking closely at the photographs in the album, which spanned my father’s first 40 years. The snapshots portrayed my father first as in infant in his father’s arms; as a toddler, a schoolboy, and then a young adult at McGill University’s Medical School; as a surgeon lieutenant in Canada’s navy at the end of the Second World War; and as a career man/medical officer climbing the corporate ladder at Canadian National Railways.

As a daughter, I find the aggregate of the album heart-wrenchingly moving—not least because I had never before seen any images of the early portion of my father’s life. I regret not knowing the silent stranger in the photographs. As a boy, as a young adult, he is someone whose future lies ahead of him, who had not yet become the distant, disapproving father that my brother and I knew, and so I wonder about the Peter Vaughan whose story this photo album suggests. Who is this individual? How does this collection of pictures suggest my father’s antecedents?

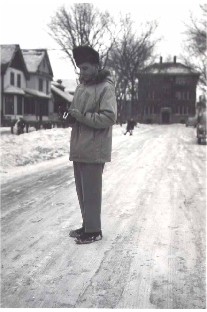

To find out, I resolved to dive deeply into certain images culled from my father’s archive, among them the image in .11 Like a very few of the snapshots, this one has some identifying notes scribbled on the back: Winnipeg, 1953. My father seems to be fiddling with a camera, anticipating his work as the official photographer of our family. I particularly liked this image for that reason, and also because it shows him in clothing that I recognize from my childhood: a parka, an astrakhan envelope hat, neatly pressed trousers, and rubber overshoes.

As I scrutinized this and other images from the album, I was working on my first research question, wondering what, exactly, it was that art “knew.” What did these photographs know, and what could I mine within them to incorporate into my work?

To link my observations to others’ work, I went to theory: I explored the writings of scholars and practitioners of domestic photography, who describe how we have come to understand family photographs to mean, to instruct us (e.g., see Barthes, 1981; Hirsch, 1997, 1999; hooks, 1995; Kuhn, 1995; Langford, 2001; S. M. Smith, 1998; Spence, 1986; Spence & Holland, 1991). Looking at family snapshots, these theorists have proposed, we see and learn not only conventions of this representational form but also how we are supposed to behave in our families, how we are supposed to present ourselves to conform to familial and social expectations.

As S. M. Smith (1998) has written of family photographs,

In these everyday portraits we learn to see ourselves and our families. We see how we have learned the poses that situate us in relation to others. And we see how we have failed to meet the ideal visions we sensed hovering behind the commands to “Look over here” and “Smile!” And sometimes, in the gap between these repetitions and slippages, we sense that perhaps our “failures” mark our rejection of the frames that homogenize and normalize. Perhaps in the images we “ruined” we can see ourselves emerging. (p. 181)

While I scanned my father’s photos for repetitions and slippages, I also took clues from the clothing that my father wears in the pictures that touch me the most. Here, too, theory helped: I explored writings and images from the history of textiles and the emerging discipline of fashion theory (Baert, 1998; Barber, 1994; Conroy, 1999; Entwistle, 2000; Lawrence & Obermeyer, 2001; Mara, 1998). I am reminded that clothing reflects a border between our selves and the world, between individual preferences of self-presentation and accepted norms. Still, clothing is profoundly personal, a kind of surrogate we imprint ourselves on. As Stallybrass (1993) has written,

The magic of cloth . . . is that it receives us: receives our smells, our sweat, our shape even. And when our parents, our friends, our lovers die, the clothes in their closets still hang there, holding their gestures, both reassuring and terrifying, touching the living with the dead. But for me, more reassuring than terrifying, although I have felt both emotions. For I have always wanted to be touched by the dead. (p. 36)

As I read and considered, I decided to make a series of five textile sculptures that would take their starting points in the garments that my father wears in five affecting photographs. Although I had previously worked primarily in two dimensions, the sculptural form insisted itself. By creating life-sized, three-dimensional clothing sculptures, I could through my own body begin to relate to my father’s experiences of his actual attire—of the feel of the cloth on skin; of the tightness of waistbands, shoulder seams, wrist and ankle cuffs; of cocooning warmth and weight. To some extent, I re-created his experience in making my artifacts. Similarly, textile historian Barber (1994) set up her loom and wove patterns she had found in fragments of ancient cloth to understand their makers’ practice and, by extension, aspects of the world in which the original weavers lived (pp. 17-24).

However, unlike the garments in the photographs, my clothing sculptures are unwearable. Why is this crucial? So that the desire to put on the article can never be realized. Unwearability emphasizes loss—not just of the garment’s actual use but of all I have stitched into it: my father’s history; my father’s youth; my father’s ability to tell his own stories, my father himself. Unwearable, my “clothing” will emphasize its deviation from the tradition of human attire and raise issues concerning theoretical and symbolic aspects of dress. In this way, my work reaches beyond personal resonances into the realm of the social/cultural.

How would I make these garments unwearable? Primarily, by designing them to accommodate the complexities and ambiguities of psychological wounds rather than the standardized physicality of an unblemished human form. This was a man who through most of my childhood could not relate to his children, who had limited avenues of personal expression, and who hid behind his newspaper and commuter routine rather than take on significant challenges within our family. Yet, my father was also the man who in my youngest years gave me world-opening books and music recordings, as well as wigs and costumes to dress up in; who chose for me an idiosyncratic doll who was my childhood’s constant companion; and whose face, in my collection of family photographs, I see lit with joy as he plays with his infant daughter.

I aimed to make sculptures that invoke these complexities and contradictions. Gazing at the figure and his attire in a chosen photograph, I imagined my father’s inner realities and extrapolated the body that reflected these. Then, I designed and created a garment to clothe it. I exaggerated shapes, materialized the invisible, embellished with the uncomfortable, insisted on the impractical. I aimed to make sculptures that are both beautiful and grotesque with human failings, that, in the tradition of S. M. Smith’s (1998) “ruined photographs” (p. 181), are ruined articles of clothing. Given the clothing my father wears in the photograph in Figure 2, it is not surprising that for one of my sculptures, I imagined and sketched an unwearable parka.12

Figure 2: Dad [Peter Vaughan] in Winnipeg

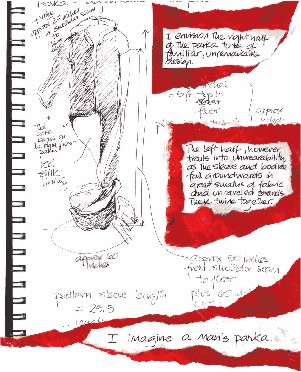

A sketchbook collage, Figure 3 includes not only my preliminary drawing of and measurements for the parka I would make but also some excerpts of my writing about my design on fields of red, red being a recurring element of this series of sculptures. Red, of course, links to blood and body, to passion and sacrifice, to the fleshy family bonds that tie us into relationships.

Figure 3: I imagine a man’s parka

In my mind’s eye, the parka hangs suspended in midair, just above the height of a middling-sized man. I envision the right half of the parka to be of familiar, unremarkable design. The left half, however, trails into unwearability, as the sleeve and bodice fall groundward in great swaths of fabric and unraveled strands. These twine together and circle what would be the feet of the invisible wearer-part winding cloth, part straitjacket, part exultation of color, texture, and form.

In choosing to redesign the left side of the parka, I consider the attributes ascribed to “left” in our right-ist culture. In Old English, the roots of the word left mean weak and worthless (Macdonald, 1976, p. 751). Our English sinister derives from the Latin for left; and we use the French gauche to signify awkward or inept-just what a person would be who had the body for which my unwearable parka is designed. This hypothesized inadequacy, however, is undone by other language-based tropes: “the long arm of the law,” for one. In such usage, the long arm has scope and potency. This opposing meaning adds complexity that appeals to me.

In his photo (see Figure 2), my father stands with his left side to the camera. Surprisingly, it is his left, nondominant hand that appears to be in the process of making a delicate adjustment to his camera. I remember that when my brother and I were young, we would compete good-naturedly for the chance to hold my father’s left hand. His left hand was close to two magical attributes, his watch and his forearm’s snake-and-anchor tattoo, whereas his right hand and arm were bare. I remembered that my brother and I had designated my father’s left hand as precious long after I had decided to remake the left side of the parka, to making that phantom left limb the unreachable/unreaching one.

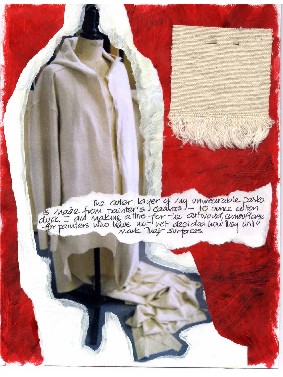

I decided to create the outer shell of my parka from soft, washed yards of painter’s canvas, 10-ounce cotton duck. I was making attire for the art world, camouflage for painters who have not yet decided how to mark their surfaces. Because my design incorporates a coil of cloth at the base of the sculpture, I approximated the yardage needed for this effect, then bought 10 yards of canvas at the art supply store around the corner from my studio. The cloth was crisp with sizing, which I washed out. I then dried and ironed my newly supple cloth.

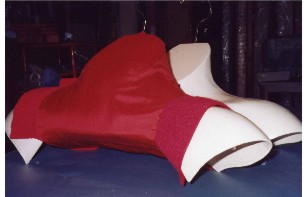

I adapted a commercial pattern to my own design, cut my pieces, and pinned them into position. At a sewing machine for the first time since Grade 9 home economics classes, I stitched my soft pieces into a parka’s shell (Figure 4). I could see that my parka needed some bulk, some stiffening, beyond the minimal support that silk lining would provide. For my batting, I settled on burlap—another kind of raw material for painters. I cut a double layer of each pattern piece, and then stitched the two layers together along a two-inch grid. This grid of stitchery adds resistance to the loosely woven cloth, ensuring that it will hold its shape.

Figure 4: The outer layer of my unwearable parka

The aliveness of the process-based work—piecing together cloth, piecing practice with research and theory—is described vividly by Eisner (2002):

In the process of working with the material, the work itself secures its own voice and helps set the direction. The maker is guided and, in fact, at times surrenders to the demands of the emerging forms. Opportunities in the process of working are encountered that were not envisioned when work began, but that speak so eloquently about the promise of emerging possibilities that new options are pursued. Put succinctly, surprise, a fundamental reward of all creative work, is bestowed by the work on its maker. (p. 7)

Eisner (2002) also suggested that it is from surprise that we are most likely to learn.

In my case, well into the making of my unwearable parka, I was surprised by the realization that I had not resolved issues of hanging and installation. Just how was I going to present my parka—or any of the other works in the series? I wanted the sculptures to be free floating, but the garments were built to convey heft and so would be heavy to hang. I had not thought to integrate any kind of armature into the lining of the jacket. Now, I would have to add a support that would bear the weight of the parka while allowing it to hang around a suggestive void: It is essential that my unwearable clothing adorn an absent body, one whose contours conform to the strangeness of my designs.

At this point, I recognized that this notion of the absent body was as vital to the thematics of this work as is its unwearability. In terms of my first question, What does art know?, I wanted this piece to know the body of an absent wearer, not simply to be an unwearable garment waiting never to be put on, but one that had been inhabited by an imaginable absence. This understanding took me to researches into memory, loss, and material culture, which further enriched my art making.

Looking back on significant loss, according to Kuhn (1995), happens in one of two ways. The first is cool, tinged with “the disavowal characteristic of nostalgia” (p. 121)—a disavowal of the truth that the lost object is irretrievable, which removes the pain of remembering. The second is hot, that “frenzied lament, that painful and obsessive passion of remembrance, that struggle to come to terms with loss, which marks the work of mourning” (p. 121). Could it be, then, that the work of mourning is completed when the bereaved has remembered enough? When forgetting can begin? If so, I wonder whether a work of art that has a mourning function becomes, necessarily, partially, “a work of forgetting . . . in which remembrance is the woof and forgetting the warp” (Benjamin, quoted in Forty, p. 16).13

Accordingly, then, I imagine that my work of mourning, my creation of unwearable clothing, will be complete when I have remembered enough. This will mean that I will have summoned enough data and details about a life like that of Peter Vaughan, worked in the archives and libraries sufficiently to have come to understand the social and cultural history of a boy/man of the era of his photo album. Because I have no personal memories of him from this time, I will work to stitch together a surrogate memory, a prosthetic memory of the absent body.

To help suggest that absent form, to hold the parka open during display, I eventually found deep-shouldered display hangers (Figure 5). These I reshaped, padded, and covered with the same red silk that lines the parka so that they would be aesthetically integrated into the sculptures, adding Velcro to ensure a secure perch. In this way, one more issue of meaning and aesthetics was resolved. My parka moved closer to completion, as represented by the next image, showing a detail of the suspended parka, with lengths of dogwood stitched into the silk lining (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Two hangers, one with red silk padding and Velcro strips, one unchanged.

Figure 6: Suspended parka (detail), bodice with stitched dogwood lengths

Why dogwood? The reasons are multiple, addressing at least three meanings of the series. First, the sharpness of the twig ends serves to make the garment uncomfortable—almost a kind of hair shirt—and so emphasizes its unwearability. Second, the dogwood twigs connect the garment to the environment in which it and the absent wearer would reside: in this case, a northern, water-rich parkland (there is much botanical folklore embedded in this series). Third, the dogwood is red, reinforcing the limited palette of the series: reds and ivories, body tones and neutrals.

The aspect of my process laid out here—the documenting and presenting of the various stages of this work—conforms to suggested processes of practice-led research. This methodology proposes the use of visual and multimedia methods of information gathering, selection, analysis, synthesis, and presentation or communication (Gray, 1996, p. 15)—a project that itself suggests a collagist process of juxtaposition. Similarly, de Freitas (2002) has argued for “active documentation” in practice-led research, which can be the basis for “a valuable learning process and an indispensable script for the writing of an exegesis as part of the post-graduate submission for final examination” (p. 1). I must admit that my documentation practice has been more ad hoc than systematic. I take pictures, sketch possibilities, and write reflective notes as I feel the need, not according to an external timetable. I wonder how to invoke more system without overriding the organic nature of my process that I value so highly.14

I present a selection of my documentation images here, not to illustrate my text so much as to evoke the absent artwork, to lay bare the process of its making, and to encourage the reader’s attunement to the visual. Plus, within a traditional, scholarly format, the inclusion of images as figures is just about the only way that I can represent the visual aspects of my collage practice, my métissage, rather than simply refer to it.

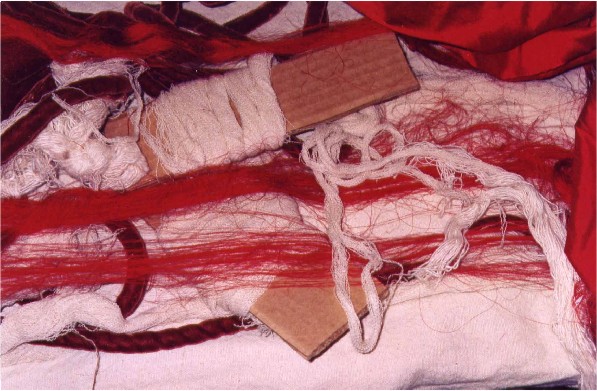

Lionnet (1989) wrote that métissage “derives etymologically from the Latin mixtus, ‘mixed,’ and its primary meaning refers to cloth made of two different fibers, usually cotton for the warp and flax for the woof” (p. 14). Given this origin of métissage in fibers, I find my use of textiles a felicitous coincidence. And in fact, long before I read Lionnet, I planned for my parka a tail of unraveled strands of warp—in this case, cotton, burlap, and silk, seen in progress in Figure 7. (The pieces of cardboard are spools to keep the long strands untangled while I work on other areas of cloth.)

The long, long, almost ritualistic process of unraveling appeals to me: occupying my hands, freeing my mind. In the hours it took to reduce yards of silk, cotton, and burlap to their component strands, I thought about my father and my sense of him. I reflected on my continuing researches into his past, the family interviews and my readings in social history about the times and influences through which a man of my father’s age, class, gender, race, and privilege would have lived. My work has been slow, just as the process of a person’s identity formation is slow.

Figure 7: Unraveling in progress, with strands of silk and cotton visible, as well as cardboard spools:

Unraveling reduces cloth to its element: string. The strands of unraveled warp retain the memory of the cloth they constituted. The strands are crimped by the woof threads, which, in weaving parlance, were “beaten” into position against the neighboring cross-yarn. Warp threads are rich in meaning: They allude to their past and suggest a readiness for a future in which they will be rewoven, integrated with other strands, other textures, other fibers, in a new design, a new fabric.

Indeed, such reintegration was a feature of my parka design. I rewove my strands, braiding them together, tying them into knots around lengths of my beloved dogwood, as a detail of the bottom portion of the parka reveals (Figure 8). I see these multiple forms of integrating fibers and the addition of dogwood all against the background of still-woven lengths of cloth, as a version of Lionnet’s (1989) process/praxis of métissage and my own vision of collage.

Figure 8: Re-raveling (métissage) in progress, with lengths of dogwood tied among strands of fiber

Before turning to the full, completed version of the sculpture, I will next suggest how I am integrating practice and theory to propose characteristics of a collage method.

Integrating theory and practice: Proposing characteristics of a collage method

Distilling this work and the ideas connected to it, what characteristics, then, would I propose for a collage methodology? I identify eight prerequisite qualities, hesitantly, provisionally, remembering Lionnet’s (1989) assertion that “métissage is a praxis and cannot be subsumed under a fully elaborated theoretical system” (p. 8).

Creative practice

A collage methodology is rooted in and led by creative practice of an experimental orientation. After all, the point of art “is not to reiterate but to innovate, to offer experiences and insights, sights and sites that we did not as yet possess” (Bal, 2001, p. 33). A collage method might yield an experimental text, a visual artifact, a web-based event—or, perhaps, a combination of new forms. Although the form of this article is quite conventional, it is rooted in and reflects a collage practice (that has also generated less conventional offerings, namely the Unwearables).

Juxtaposition

A collage practice is built on juxtaposition, on the interplay of fragments from multiple sources, whose piecing together creates resonances and connections that form the basis of discussion and learning.

Interdisciplinarity

A collage methodology is interdisciplinary, juxtaposing multiple fields of endeavor and situating the practitioner and his or her work within and between them.

Link to daily life

Like its antecedent fine arts form of expression, which incorporated bits and pieces from popular culture and everyday life, a collage methodology is linked to daily life. In this sense, it has aspects familiar to qualitative researchers from naturalistic inquiry: specific circumstances, particular experiences, and (given its arts grounding) individual creations.

However, if “the lived is to be anything more than just another mantra, another abstracted nod, then our experiences must be put squarely in the terrain of the theoretical” (Probyn, 1993, p. 21); in other words, the daily life of the individual (whether creator or, as in the case of my father, muse) must be linked to the broader context in which the individual lives or lived; that is to say, a collage method requires a situated artist/researcher.

Situated artist/researcher

The individuality and handmade-ness of an art product begins the process of situating its creator at a particular moment, a location, an identity. However, a fuller articulation and theorizing of that situated self better reflects the provisional and circumstance-dependent aspects of the project. As arts-based educational theorist Finley (2001) has proposed, “the structures of collage simultaneously emphasize personal meanings, history, culture, and tradition in such a way as to bring disparate voices of the internal-personal and external-contextual to a common place” (p. 17), giving the individual artifact a broader resonance.

Culture critique and transformation

A collage practice is oriented toward the broader sweep of cultural critique and transformation of at least two kinds. The first is aesthetic transformation, which has as its aim, in the words of Greene (1995), “to enable people to uncover for the sake of an intensified life and cognition” (p. 125). The second is political transformation through the labor to, as hooks (1990) has described it, “create space where there is unlimited access to pleasure and power of knowing” (p. 145).

Open-endedness

The work of a collage practice is open-ended. No individual activity can be described as definitive. Rather, each work (this article, for example) represents the practice at a particular moment: Its form and content reflect the juxtaposition of individual ideas, realms of thought, texts, images, and other creative works, and the conversation that develops between them.

Multiple, provisional, and interdependent products

Accordingly, the products of a collage practice are multiple, provisional, and interdependent. The creating of each fragment, each articulation—be it text, artwork, or some combination of forms—influences and is influenced by the others.

This means that a collagist methodology does not follow the most prevalent models of practice-led research, in which a written exegesis accompanies, describes, and elaborates the central work of a visual art installation (see AHRB, 2003, p. 4) and serves the primary purpose of either positioning the practice within contemporary creative and research contexts or theorizing the practice. Rather, the interdependent components of a collagist inquiry aim above all to reveal the practice (see Macleod, 2000, p. 2).15 The interdisciplinary work is embodied, not simply described, in each component.

Products that reflect, reveal, and document the process

The products of a collagist method reflect, reveal, and document the process of their own creation. In doing so, they situate themselves and their maker in a particular context or, perhaps, an unfolding array of contexts. Among other important effects, this representation deromanticizes the creative process, bringing the important scholarly requirement of transparency to the inquiry.

˜˜˜

I recognize that this article and the work that I explore in it reflect some of these qualities more than others and less, I hope, than later incarnations ultimately will. I account for this by the fact that my Unwearables are still in progress—only two of the five planned works are complete—and so I am theorizing at the very edges of my experience and research. My belief is that airing this work in progress will begin some and continue other conversations—about art, about research, about method.

A similar point was made by Douglas and her colleagues (2000) in practice-led research. They wrote,

The aim and outcome of the research process, in all its manifestations, is not to reach consensus on a single “correct” model of research—but to raise informed debates by locating and communicating research activities. The proposing and evaluating of different interpretations of the practice/research relationship becomes a vital characteristic of our research culture (p. 2).

By extension, teasing out the relationships between arts-based, practice-based or collage research and other kinds of inquiry can also enrich our research culture. In other words, our work as researchers is itself partly about the conversation between us—about the “collage” our methodologies create together. Arts-based researcher Mullen (2003) wrote, “If we rally to hear one another . . . then we can enter spaces that transcend absolute positions that would other wise produce closed scripts. Our scripts, our selves, must remain open” (p. 173).

Writing from a similar perspective is Canadian artist Frenkel (2001), who suggested that an interdisciplinary practice is like a Creole, bursting with hybrid vigor, asking questions rather than making statements. She continued, “Thread by thread, gesture by gesture, in a special kind of intermediality, such [interdisciplinary] work weaves frail and precarious connections across the spaces between locked-in meanings on either side” (p. 41). Frenkel’s weaving imagery suggests another reason why textile forms, with their frailties and aggregates, have suggested themselves for the visual artworks I am making in my interdisciplinary doctoral studies.

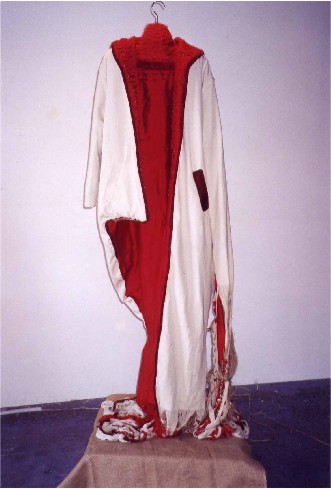

Unwearable: Parka is at last done, and seen entire in Figure 9.16 Here, I have accomplished my last labor: I have for hours stitched lengths of red dogwood into the extravagant length of lining, making my parka increasingly uncomfortable, beautifully unwearable, and, I believe, an evocative representation of my father and others—perhaps of his race, class, gender, location, and time, or perhaps not.

Figure 9: Unwearable: Parka

Fresh from the hours of tactile textile work, I am less attuned to the arm’s-length visuality of the completed and installed Unwearable: Parka than I am to the proximate processes of its making, and so I spend time looking, attempting to see the work afresh. Standing in front of the installed piece, I encounter a slightly more than human-sized sculpture that surprises me with its cool beauty and self-containment. As a whole, the sculpture presents an order, a dignity, despite ragged edges and raveled strands. These disabilities—so looming in my own mind during the design and creation—now seem secondary to the intact presence of the work as a whole. Even the questions provoked by visual dissonances—Why is one pocket flap rust-colored velvet?—are quiet murmurs rather than urgent peals.

Parka’s unity is reinforced as I walk around the sculpture, slowly taking in its every angle. I move clockwise, first encountering the areas of traditional design: the sleeve that would fall unremarkably to a man’s wrist, the thigh-length front panel. The strong diagonal of the hem as it dives groundward plays against the sculpture’s soaring vertical thrust. The sculpture’s long, lean uprightness is even more dominant from behind, where the full-length ivory of the canvas “skin” is uninterrupted. Only a glimpse of the blazing red of the hood’s silk lining, the rust velvet piping accentuating its edge—only these disrupt the clean, consistent external surface. This long expanse of unblemished cloth separates the viewer from the embellished innards of the parka, imposing a kind of stillness, a silence on the emblematic scarlet and perplexing stitched dogwood lengths.

These gradually come into view as I continue my clockwise walk around the piece. I pause beside the floor-length sleeve and take in the rupture between the cloth and its constituting threads. I notice the burst of textures, the loops and strands, the knots and braids, the occasional twig. Here, I see burlap, intact and in silvered brown strands, suggesting how I have achieved the parka’s visual weight, the allure of embracing coziness—contradicted as soon as I move to face the Parka and its inner shell of sharp twig ends. These are not cozy; these are pain, ritualized by the regularity, the obsessiveness of their horizontal gridding. From the front, I see that the “subject position”—that is, the place that the viewer is implicitly invited to assume with respect to an artwork—is impossible. The Parka hangs open, empty, offering access, refuge, embrace; and yet fearing pain, one dares not put it on. In this contradiction resides a central meaning of this work: The Parka is unwearable.17

Conclusion

Through this work of making, researching, theorizing, I have come to understand that the Unwearable series is about me as much as it is about my father, and my own work to reclaim and represent concepts of knowledge, art, and participation in the world. I have the privileges and responsibilities of this collagist endeavor, and the pleasures of recognizing, in the words of Finley (2001), that “being an artist depends upon my skills and approaches to doing research and being a researcher depends equally upon the methods of my art” (p. 15).

I also believe that this work is about more than my family’s stories. Rather, it is my way of “thinking the social through myself” (Probyn, 1993, p. 3). Like other scholars and artists working with the family, I believe that

embedding family photographs in a comparative and theoretical discourse, and representing them in new artistic work, will allow us not only to see them anew, but also to examine the power of the metaphor of family in contemporary cultural discourse. (Hirsch, 1999, p. xvii).

I hope my work will raise questions about the politics of representation and the intersections of personal and public life embodied in domestic photography, reminding viewers/scholars that the personal truly is political.

In other words, my Unwearable inquiry not only reflects my version of my father’s biography but also embodies a broader story that, I have come to see, is about the potential impacts of education. This education, whether pursued in the family, in a private boy’s school, during professional training, in the military, or within corporate culture, leaves its marks. My Unwearables propose that this mark is felt in the body, in the person’s link to natural and bodily rhythms, in the person’s affections and abilities to move unimpeded in the world. I will elaborate these meanings as I continue to work on other Unwearables.

My collage practice also links me to the questioning, experimental work current in social science and humanities research. In 1994, in the first edition of their Qualitative Research Handbook, Denzin and Lincoln suggested an immediate future for qualitative research that is very akin to collage. They anticipate that “messy, uncertain, multivoiced texts, cultural criticism, and new experimental works will become more common, as will reflexive forms of fieldwork, analysis, and intertextual representation” (p. 15). By 2000, when the second issue of the Handbook was issued, Gergen and Gergen referred back to this remark, proposing that within this matrix of uncertainty lies the innovative power of qualitative inquiry to transform the social sciences and alter the trajectories of our cultures (pp. 1042-1043). I hope so, for, like other practitioners at this time, my ultimate agenda is liberatory:

To engage in critical postmodern research is to take part in a process of critical world making, guided by the shadowed outline of a dream of a world less conditioned by misery, suffering, and the politics of deceit. It is, in short, a pragmatics of hope in an age of cynical reason. (Kinchloe & McLaren, 1994, p. 154)

I do not yet know how energetically my Unwearables move in this direction. I hope to see their transformative aspect more clearly as I complete the series, and I inflect my continuing work with this intention. However, if it is true that, as Marcus and Fischer (1999) have proposed, “in periods when fields are without secure foundations, practice becomes the engine of innovation” (p. 166), then there is broader relevance in my practice-led research/creation, in my Unwearables as work necessary to their time.

In these ways, then, this article begins to answer its opening question. Why would an artist want to take on the work of a PhD? To embed my own work more deeply in the experimental tenor of these times, to work toward ensuring that more of us appreciate what art knows and to find ways to explore and represent that knowledge, and to find personally appropriate ways to work with the arts’ emancipatory potential and effect social change.

Notes

1. All documentation photographs © Kathleen Vaughan, 2002, 2003, 2004. back to text

2. I have been assisted in distinguishing between method and methodology by definitions offered by Gray and Pyrie (1995), quoting the 1982 edition of the Collins Dictionary.

Methodology:

1. the system of methods and principles used in a particular discipline.

2. the branch of philosophy concerned with the science of method.

Method:

1. way of proceeding or doing something, especially a systematic or regular one.

2. orderliness of thought, action, etc.

(often pl.) the techniques or arrangement of work for a particular field or subject. (p. 2) back to text

3. Theorists from fine arts and the social sciences have borrowed the term bricolage from the work of Lévi-Strauss (1966), who used it to suggest a playful piecing together (p. 17), as well as Ulmer (1989, p. 385), who linked bricolage with collage. Denzin and Lincoln (2000, p. 4) have offered a full discussion of the ins and outs of the term with respect to qualitative research. back to text

4. Scholars who are not artists and who wish to explore how collage might enhance their qualitative research practices can glean insights and ideas from the work of Davis and Butler-Kisber (1999) and of Butler-Kisber and Borgerson (1997). back to text

5. I am aware that Eisner has a more recent formulation of the eight defining characteristics of arts-based educational research, proposed at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) Winter Institute in 2001. I have chosen to highlight the earlier criteria, as those do not explicitly require that the research be about educational phenomena—first on Eisner’s newer list. I situate my work as interdisciplinary, with resonances into education, and so the narrower definition does not suit my purposes (See Eisner, 2001). back to text

6. See, for instance, the abundant and diverse examples of arts-based research in Bagley and Cancienne (2000); Dunlop (1999); , Neilsen, Cole, and Knowles (2001); and Norris (1997). Other instances can be found in special arts-based editions of journals: Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 48(3), Fall 2002; Educational Theory, 45(1), Winter 1995—A Symposium on the Arts, Knowledge and Education; Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 17(2), Summer 2001—Special Issue on Performances in Arts-Based Inquiry; Qualitative Inquiry, 9(2), April 2003—Special Issue on Arts-Based Approaches to Qualitative Inquiry; and Qualitative Inquiry, 9(4), August 2003—Special Issue on the Arts and Narrative Research, Art as Inquiry. back to text

7. I have been intrigued to learn that in the United Kingdom, at least, practice-based doctorates are also being sought by teachers, nurses, civil servants, police officers, and doctors inquiring into aspects of their respective professional practices. According to the sources I consulted, this phenomenon reflects the changing social and political landscape, in which closer ties are being sought between higher education and the working world. Governments and the educational institutions they fund seem to emphasize the uses of higher education for wealth creation, whereas workplaces are moving toward encouraging academic credentials (see Winter, Griffiths, & Green, 2000, pp. 26-28). back to text

8. It is now possible to pursue a practice-based doctorate in more than 40 departments in U.K. institutions (Candlin, 2000, p. 97). back to text

9. According to British artist-scholars, what distinguishes practice-led research from creative practice (which, of course, often includes a component of research) is that in the former, “a degree of validation has to be reached for knowledge to be recognised by the academic context, and to be passed on through teaching.” Or so suggests some of its practitioners, specifically Douglas (2000, p. 6). Policy makers and funding bodies agree, stating that research/creation must be able to be shown to be firmly located within a research context; subject to interrogation or critical review, and having an impact or influences on the work of peers, policy, and practice; and with a teaching aspect (see Centre for Research in Art and Design [CRiAD], n.d.; SSHRC, 2003, pp. 3-4). This latter might reflect the fact that the etymological origin of the term doctorate is docere, to teach (Winter et al., 2000, p. 36). back to text

10. Lionnet (1989) borrowed the term métissage from the work of the Martinican poet Glissant, who invoked it as a way of braiding together revalorized oral traditions and reevaluated Western concepts (p. 4). It is also worth noting that in her theorizing, Lionnet invoked a term familiar from earlier mentions in this article: she describes métissage as a “form of bricolage, in the sense used by Claude Lévi-Strauss, but as an aesthetic concept it encompasses far more: it brings together biology and history, anthropology and philosophy, linguistics and literature” (p. 8). back to text

11. Black-and-white photo, 3 7/8 inches by 2 7/8 inches (9.7 by 6.25 cm). Photographer unknown, ca. 1950. back to text

12. The four other Unwearables are a baby’s mohair jumpsuit, a schoolboy’s woolen athletic sweater and socks, a lab coat, and a dress naval jacket. back to text

13. Benjamin used this phrase to characterize Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. back to text

14. The work of de Freitas (2002) suggests to me that active documentation might be a means of addressing issues such as my first research question, What does art know? She wrote, “The process of moving intellectually or creatively from the known (present position) to the unknown (next position) is an inherent part of studio practice and evidence of its occurrence is an important aspect that should be included in an exegesis” (p. 16). Perhaps the imperative to document those leaps in intuition, cognition, and creativity as and when they occur is sufficient structure for a practice of documentation. back to text

15. In addition to proposing these useful (although, to my mind, not necessarily mutual exclusive) categories, Macleod (2000) offered a formulation of the interplay of interdependent components of an inquiry (texts, images, video, etc.) that is the closest I have found to my vision of the back-and-forth workings of an integrated collage practice. As she described it, the written text was instrumental to the conception of the art projects but the art projects themselves exacted a radical rethinking of what had been constructed in written form because the process of realizing [again, this is a quotation from a pub with English spelling. Do we change those?] or making artwork altered what had been defined in written form. (p. 3). back to text

16. Unwearable: Parka (2001/04) as installed, approximately 79 inches (201 cm) high by 33 inches (84 cm) wide by 5 inches (12.5 cm) deep. Media include unbleached cotton painter’s canvas, burlap, velvet, silk, lycra/cotton jersey, dogwood twigs, polyester and cotton threads, molded plastic and metal hanger, foam padding, Velcro, and nylon fishing line. Photo: Paul Buer. back to text

17. In my approach to describing the completed Parka, I am indebted to the work of Bal (2001) on Bourgeois’ Spider. back to text

References

Arts and Humanities Research Board. (2003). The RAE and research in the creative & performing arts. Retrieved October 4, 2003, from http://www.ahrb.ac.uk/ahrb/website/strategy/ response/the_rae_research_in_the_creative_performing_arts.asp?ComponenetID=92883&SourcePageID=92887#1

Baert, R. (1998). Three dresses, tailored to the times. In I. Bachmann & R. Scheuing (Eds.), Material matters: The art and culture of contemporary textiles (pp. 75-91). Toronto: YYZ Books.

Bagley, C., & Cancienne, M. B. (Eds.). (2002). Dancing the data. New York: Peter Lang.

Bal, M. (2001). Louise Bourgeois’ Spider: The architecture of art-writing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Barber, E. (1994). Women’s work: The first 20,000 years. New York: Norton.

Barthes, R. (1981). Camera lucida: Reflections on photography (R. Howard, Trans.). New York: Hill and Wang.

Brockelman, T. P. (2001). The frame and the mirror: On collage and the postmodern. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Butler-Kisber, L., & Borgerson, J. (1997, March). Alternative representation in qualitative inquiry: A student-instructor retrospective. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago.

Candlin, F. (2000). Practice-based doctorates and questions of academic legitimacy. Journal of Art and Design Education, 19(1), 96-101.

Centre for Research in Art and Design. (n.d.). Definition of research. Retrieved October 4, 2003, from http://www2.rgu.ac.uk/criad/r2.htm

Conroy, D. W. (1999). Oblivion and metamorphosis: Australian weavers in relation to ancient artefacts from Cyprus. In Sue Rowley (Ed.), Reinventing textiles, volume 1: Tradition and innovation (pp. 111-131). Winchester, UK: Telos.

Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. London: Sage.

Davis, D., & Butler-Kisber, L. (1999, April). Arts-based representation in qualitative research: Collage as a contextualizing analytic strategy. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, QC.

de Freitas, N. (2002). Towards a definition of studio documentation: Working tool and transparent record. Working papers in art & design (Vol. 2). Retrieved March 11, 2003, from http://www.herts.ac.uk/artdes/research/papers/wpades/vol2/freitasfull.html

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln. Y. S. (1994). Introduction: Entering the field of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1-17). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed, pp. 1-28). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dimitriadis, G., & McCarthy, C. (2001). Reading and teaching the postcolonial: From Baldwin to Basquiat and beyond. New York: Teachers College Press.

Douglas, A. (with Scopa, K., & Gray, C.). (2000). Research through practice: Positioning the practitioner as researcher. Retrieved October 28, 2002, from http://www.herts.ac.uk/artdes/simsim/conex/res2prac/

Dunlop, R. (1999). Boundary Bay: A novel as educational research. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Dunlop, R., Vaughan, K., & Barnett, V. (2003, October). Geography, body, memory: The education of girls and the construction of feminist identities. Performative panel presentation at the conference on Diaspora, Memory, Silence, Toronto.

Eisner, E. W. (1997). The promise and perils of alternative forms of data representation. Educational Researcher, 26(6), 4-10.

Eisner, E. (2001). Some features of arts-based research. Unpublished manuscript, American Educational Research Association Winter Institute.

Eisner, E. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Eisner, E., & Barone, T. (1997). Arts-based educational research. In R. M. Jaeger (Ed.), Complementary methods for research in education (2nd ed., pp. 73-94). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association. (Original work published 1988)

Entwistle, J. (2000). Fashion and the fleshy body: Dress as embodied practice. Fashion Theory, 4(3), 232-348.

Finley, S. (2001). Painting life histories. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 17(2), 13-26.

Finley, S., & Knowles, J. G. (1995). Researcher as artist/Artist as researcher. Qualitative Inquiry, 1(1), 110-142.

Forty, A. (1999). Introduction. In A. Forty & S. Küchler (Eds.), The art of forgetting (pp. 1-18). Oxford: Berg.

Frenkel, V. (2001). A kind of listening: Notes from an interdisciplinary practice. In L. Hughes & M.-J. Lafortune (Eds.), Creative con/fusions: Interdisciplinary practices in contemporary art (pp. 30-47). Montreal, QC: Optica.

Gergen, M. M., & Gergen, K. J. (2000). Qualitative inquiry: Tensions and transformations. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 1025-1046). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gray, C. (with Douglas, A., Leake, I., & Malins, J.). (1995). Developing a research procedures programme for artists & designers. Retrieved October 28, 2002, from http://www2.rgu.ac.uk/criad/cgpapers/drpp/drpp.htm

Gray, C. (1996). Inquiry through practice: Developing appropriate research techniques. Retrieved January 25, 2004, from http://www2.rgu.ac.uk/criad/cgpapers/ngnm/ngnm.html

Gray, C., & Malins, J. (1993). Research procedures/methodology for artists & designers. Retrieved October 4, 2003, from http://www2.rug.ac.uk/criad/cgpapers/epgad/epgad.html

Gray, C., & Pyrie, I. (1995). “Artistic” research procedure: Research at the edge of chaos? Retrieved November 2, 2002, from http://www2.rgu.ac.uk/criad/cgpapers/ead/ead.htm

Green, J. R. (2000, May). Maximizing indeterminacy: On collage in writing, film, video, installation and other artistic realms (as well as the Shroud of Turin). Afterimage. Retrieved January 16, 2004, from http://www.findarticles.com/ cf_dls/m2479/6_27/63193945/print.jhtml

Greene, M. (1995). Texts and margins. In R. W. Neperud (Ed.), Context, content, and community in art education: Beyond postmodernism (pp. 111-127). New York: Teachers College Press.

Harding, S. (1996). Science is “good to think with”: Thinking science, thinking society. Social Text 46/47, 14(1/2), 15-26.

Hirsch, M. (1997). Family frames: Photography, narrative and postmemory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hirsch, M. (1999). Introduction: Familial looking. In M. Hirsch (Ed.), The familial gaze (pp. xi-xxv). Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Hoffman, K. (1989). Collage in the twentieth century: An overview. In K. Hoffman (Ed.), Collage: Critical views (pp. 1-37). Ann Arbor: MI: UMI Research Press.

hooks, b. (1990). Yearning: Race, gender, and cultural politics. Boston: South End.

hooks, b. (1995). In our glory: Photography and black life. In b. hooks, Art on my mind: Visual politics (pp. 54-64). New York: New Press.

Kinchloe, J. L., & McLaren, P. (1994). Rethinking critical theory and qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 138-157). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kuhn, A. (1995). Family secrets: Acts of memory and imagination. London: Verso.

Langford, M. (2001). Suspended conversations: The afterlife of memory in photographic albums. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Lather, P. (1997). Creating a multilayered text: Women, AIDS, and angels. In W. G. Tierney & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Representation and the text: Re-framing the narrative voice (pp. 233-258). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Lawrence, K., & Obermeyer, L. (2001). Voyage: Home is where we start from. In J. Jefferies (Ed.), Reinventing textiles, volume 2: Gender and identity (pp. 61-75). Winchester, UK: Telos.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1966). The savage mind (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levin, K. (1989). Foreword. In K. Hoffman (Ed.), Collage: Critical views (pp. xix-xx). Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press.

Lionnet, F. (1989). Autobiographical voices: Race, gender, self-portraiture. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Macdonald, A. M. (Ed.). 1976. Chambers twentieth century dictionary. Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers.

Macleod, K. (2000). The functions of the written text in practice based PhD submissions. Selected working papers in art & design, 1. Retrieved March 7, 2004, from http://www.herts.ac.uk/artdes/research/papers/wpades/vol1/macleod2.html

Mara, C. (1998). Divestments. In K. Dunseath (Ed.), A second skin: Women write about clothes (pp. 57-60). London: Women’s Press.

Marcus, G. E., & Fischer, M. M. J. (1999). Anthropology as cultural critique: An experimental moment in the human sciences (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mohanty, C. T. (2003). Feminism without borders: Decolonizing theory, practicing solidarity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mullen, C. A. (2003). A self-fashioned gallery of aesthetic practice [Guest editor’s introduction. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(2), 165-181.

Neilsen, L., Cole, A. L., & Knowles, J. G. (Eds.). (2001). The art of writing inquiry. Halifax, Canada: Backalong Books & The Centre for Arts Informed Research.

Norris, J. (1997). Meaning through form: Alternative modes of knowledge representation. In J. M. Morse (Ed.), Completing a qualitative project: Details and dialogue (pp. 87-115). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Piantanida, M., McMahon, P. L., & Garman, N. B. (2003). Sculpting the contours of arts-based educational research within a discourse community. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(2), 182-191.

Poggi, C. (1992). In defiance of painting: Cubism, futurism, and the invention of collage. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Probyn, E. (1993). Sexing the self: Gendered positions in cultural studies. Routledge: London.

Smith, J. K., & Heshusius, L. (1986). Closing down the conversation: The end of the quantitative-qualitative debate among educational inquirers. Educational Researcher, 15(1), 4-12.

Smith, S. M. (1998). On the pleasures of ruined pictures. In A. Banks & S. P. Banks (Eds.), Fiction and social research: By ice or fire (pp. 179-194). Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira.

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. (2003). Research/creation grants in fine arts. Retrieved September 30, 2003, from http://www.sshrc.ca/web/apply/program_descriptions/ fine_arts_ e.asp

Spence, J. (1986). Putting myself in the picture: A political, personal and photographic autobiography. London: Camden Press.

Spence, J., & Holland, P. (1991). Family snaps: The meanings of domestic photography. London: Virago.

Stallybrass, P. (1993). Worn world: Clothes, mourning, and the life of things. Yale Review, 81(2), 35-50.

Stoller, P. (1997). Sensuous scholarship. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Tanaka, G. (1997). Pico College. In W. G. Tierney & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Representation and the text: Re-framing the narrative voice (pp. 259-304). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Taylor, L. (1994). Foreword. In L. Taylor (Ed.), Visualizing theory: Selected essays from V.A.R. 1990-1994 (pp. xi-xviii). New York: Routledge.

Thompson, J. (2000). A case of double jeopardy. In A. Payne (Ed.), Research and the artist: Considering the role of the art school (pp. 34-41). Oxford, UK: Ruskin School of Painting and Fine Art.

Ulmer, G. (1989). The object of post-criticism. In K. Hoffman (Ed.), Collage: Critical views (pp. 383-412). Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press.

van der Lem, P. (2001). The development of the PhD for the visual arts. Exchange Online Journal, 2. Retrieved March 7, 2004, from http://www.media.uwe.ac.uk/ exchange_online/exch2_article2.php3

Watrin, R. (1999). Art as research. Canadian Review of Art Education, 26(2), 92-100.

Winter, R., Griffiths, M., & Green, K. (2000). The “academic” qualities of practice: What are the criteria for a practice-based PhD? Studies in Higher Education, 25(1), 25-37.

| International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (1) March 2005 |