International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (1) March 2005 |

Doing autoethnography

Tessa Muncey

Tessa Muncey PhD, MA, BA (Hons) RN, HV, NDN Cert., RNT, Associate Dean: Research and Postgraduate Education. Homerton College, School of Health Studies, Cambridge, UK

Abstract: The author has argued elsewhere that individual identity is sufficiently worthy of research and more than just a deviant case. The representation of an individual’s story that contains one of society’s taboos appears to require legitimation of not only the text but also the method by which it is conveyed. This is particularly important if memory and its distortions appear to be critical features of the process. Using the four approaches described in this article, namely the snapshot, metaphor, the journey and artifacts, in combination, the author seeks to demonstrate the disjunctions that characterize people’s lives. In seeking to portray a new narrative to add to the received wisdom on teenage pregnancy, it is hoped that this multifaceted approach will demonstrate that although memories are fragmentary, elusive, and sometimes “altered” by experience, the timing and sequencing of them is more powerfully presented in this juxtaposition of themes than if they were presented sequentially.

Keywords: autoethnography, teenage pregnancy, deviant case, metaphor, identity

Citation

Muncey, T. (2005). Doing autoethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(3), Article 5. Retrieved [insert date] from http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/4_1/html/muncey.htm

Author’s Note

I acknowledge the help and support of a very wise woman called Ann Walton and the feedback from anonymous reviewers, and Aimee Ebersold-Silva, who helped me to focus this article more appropriately. This article was first presented at the Fifth International Interdisciplinary Advances in Qualitative Methods conference in Edmonton, Canada, on January 30, 2004.

Introduction

Many threads are woven into the fabric of my life, but the four that form the warp and weft are nursing, research, teenage pregnancy, and the garden. They are now so intertwined that it is hard to imagine that I ever conceived of them as separate strands. Nursing and research became interdependent as a result of the juxtaposition of my academic studies and my job. The third strand appeared insidiously in response to attendance at conferences, where, in seeking out articles exploring the concept and experience of teenage pregnancy, I found my story conspicuously absent. The fourth thread, the garden, emerged first as a consolation in the hectic nature of my life and then as the perfect metaphor for the inconstancy of truth in a relentlessly changing world. Together, these threads serve to underpin a defining experience in my life that, portrayed separately, serve only to reinforce current preoccupations with that experience.

To elaborate on the third thread, my first naïve response to rectifying the absence of my missing story was to publish an account of it. This ethnographic account of my experience of teenage pregnancy did what I believe all good nursing research should aim to do: contribute to a body of knowledge to help inform practice. The publishing of the account led to a number of realizations that stemmed from the reactions I received. The primary reaction was centered on memory. Questions such as Why now? Why not at the time? Could it not be possible that time had altered the story? and, indeed, more specifically, Was it true? I felt these questions as attacks on my integrity, and I realized that I needed to pay attention to the method of telling the story to enhance my credibility.

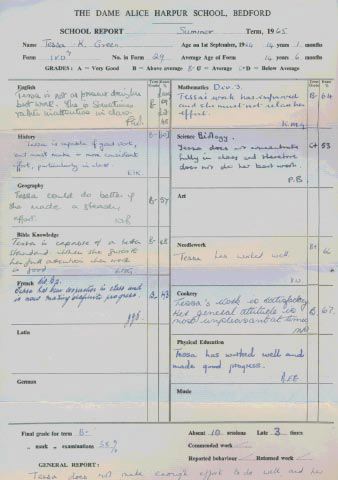

My first attempt was buried in an edited text, and reactions to it were mainly from people who knew I had written it (Muncey, 1998). One letter to a national newspaper did give space to my voice but denied my authority by withholding my name, despite my not having asked them to do so (“Tale of a Teenage Mother,” 1998). Reactions of embarrassment, irrelevance, and prurient interest in the detail seemed to dominate any associated discussion. However, these reactions gave me some insight into the problems of writing personal narrative. Because my story contains one of society’s taboos, namely sexual abuse, wider reactions ranged from accusations of self-indulgence to outright lying. So, as Tierney (1998) has suggested, to “confront dominant forms of representation and power in an attempt to reclaim . . . representational spaces that have marginalized those of us at the borders” (p. 66), I came to realize that the method I used was as important, if not more so, than the story I had to tell. My knowledge of the academic discipline of psychology prepared me for the technique of participant observation, but autoethnography allowed “a shift from participant observation to the observation of the participant” (Tedlock, 2000, p. 455).

Within this observation, I wanted to write about the whole context of my life to demonstrate that although memory is selective and shaped, and is retold in the continuum of one’s experience, this does not necessarily constitute lying. Memory is of particular significance in the discourse of sexual abuse because of the controversy surrounding recovered memories advocated by some as false memory syndrome. In an attempt to give credence to the story, a multifaceted approach is required. Because I do not fit into the stereotypical teenage mothers’ image, that is, I am educated and not financially dependent on the state, and my child has not perpetuated the cycle of teenage parenting, I am deemed to be different, and this somehow also devalues my story. I am proposing that if one wants to tell a complex story in which the disjunctions dictate that the whole is more than the sum of the parts, the method requires some portrayal of this disjunction. Fabrication of my particular patchwork life requires paying attention to physical feelings, thoughts, and emotions, which exposes “a vulnerable self that is moved by and may move through, re-fract, and resist cultural interpretation” (Ellis & Bochner, 2000, p. 7). Russel (1998) has drawn attention to the central problem of memory in this interpretation and has suggested that fragmentary recollections that are rich in detail are characterized by disjunctions. Writing “tactics” are required to draw attention to these disjunctions and the “linguistic and fictive nature [of autoethnography],” so that personal history can be implicated in larger social formations and historical processes (Fischer, 1986, p. 194). In this article, I have defined four techniques that together form a tapestry, or “art of memory,” which I employed to share my story with the academic world, namely snapshots, artifacts, metaphor, and journey, which I hope will protect against the “homogenizing tendencies of modern culture and contribute to a powerful tool of cultural criticism” (p. 194) in the context of teenage pregnancy.

The iterative nature of any research is a messy business belied by the neat conception of it in its written form. The current preoccupation with ideas informs previous experience, just as that original experience becomes the rationale for researching in the first place. As Kierkegaard (1957) suggested, life must be lived forward but can really be understood only backward, and so my own story represents this messy iteration looking backward and forward, examining images and memories through a lens that has been influenced by experience and reflection on the interaction of nursing and research, my experience of teenage pregnancy, and the window that my garden provides into the myriad of metaphors provided by nature.

Attendance at conferences increased my interest in teenage pregnancy, as I listen to the many and varied explanations put forward to explain its cause, its side effects, and its solutions. As a researcher, I am fascinated by researchers who attempt to explain the reasons for and lived experience of the pregnant adolescent. I have listened to those that advocate earlier sex education versus those who would encourage wider distribution of contraception. However, as someone who became pregnant at 15, I feel uncomfortable with the official versions of that experience. My disappointment in what I heard culminated in the publishing of an autoethnographic account to fill the void. I set out to use my journey of enlightenment to illustrate how the seemingly deviant case can challenge the existing discourse and give a voice to the world of meaning that might have been unheard. Wittgenstein (1953) thought of the relationship between truth and reality as the same as between a picture and what it represents, and pictures have come to play a significant part in the recounting of my story. The snapshot is a moment frozen in time. It is both literally a picture of something and a symbolic representation of such moments. The first useful autoethnographic technique I propose is the snapshot.

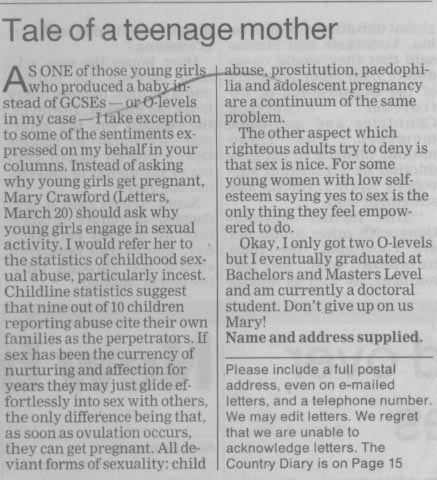

The snapshot

As a little girl, all I wanted was to belong. I watched other children playing and did not know how to join in. The rules were a mystery, the secret of which were hidden under lock and key. When I later came to describe my decision to enter nursing, I always claimed that it was a pragmatic decision not influenced by any girlish longing or vocational aspiration. I was penniless, and I needed a job that was interesting enough to tempt me away from staying at home to look after my son. Little did I know that lurking in the family album was evidence that a subliminal seed might have been sown in my formative years. Dressed up for the Coronation party of our present Queen, here I am displaying all the angelic qualities of the stereotypical nurse (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Only 13 years later, I entered the state of matrimony to escape the threat of having my child adopted. Belonging to a man saved me in a way that no independent decision to keep my child could. The formal precision of the wedding portrait distorts the reality of my complex life, a struggle that was being enacted between authority figures and personal wishes. This picture “states, announces, and symbolizes” a convincing illusion of reality. The photographer has “the mastery of the gaze,” (King, 1992, p. 131) wherein the subjects are encouraged to play the role of being desirable (Figure 2). It fits with Kuhn’s (1991) idea that family photography is an industry characterized by held-off closure, happy beginnings, happy middles, and no endings to all the family stories. Spence and Holland (1991) referred to family photographs as symbolic images not just immortalizing the individual or group but betraying all the conventions of gender-specific behaviors. There is no evidence here of the conflicts, fears, and desires that I certainly had at the time. It sanitizes the people and denies the real hardship and stress of my life at that time.

Figure 2

Less than 4 years later, I appear in a group of young women who are instantly recognizable as nurses (Figure 3). One particular experience as a District Nurse epitomizes the commonly perceived image of the nurse. I was often asked by patients if I had ever considered being a “proper nurse” and approached this query with polite reference to the need for all nurses to be qualified. However, one such query stands out in my mind, because I pursued the questioner more fully. I had gone to a house to visit an elderly gentleman who needed a dressing renewing to his legs; his son took a considerable interest in the proceedings and duly challenged me with the “proper nurse” ultimatum. On further questioning of what a proper nurse would be like, he offered the following set of attributes: wear an upside-down watch, black stockings, and frilly cap; and work in a hospital under the close supervision of a doctor. Clearly, I met none of these criteria, and not for the first time did I have cause to reflect on whether I really was a proper nurse. Warner (1994), in her Reith lectures, reiterated how myths are perpetuated through cultural repetition. She reemphasized the way in which they can make sense of universal matters and that by trying to understand and clarify them, it is possible to “sew and weave and knit different patterns into the social fabric and that this is a continuous enterprise for everyone to take part in” (p. xiv). The uniform is an important component of the nurse’s public image. A uniform is the dress worn by members of the same body, but it is interesting to note that the adjective uniform means to be “unchanging in form or character” or “conforming to the same standard or rule” (Brookes, 2003). Although the mode of apparel can seem to be relatively unimportant, it clearly has symbolic value and is closely related to matters of professional role, morale, and prestige. Reflecting on whether I was a proper nurse had parallels in the doubts I had as to whether I was a proper mother. The more distanced I felt from my perception of the norm in both areas, the more I struggled to conform.

Figure 3

The need to belong and fit in led to fragmented memories around this time. Although reflections on this photo conjure up quite a painful time in my life, to the outside world, I worked hard and appeared successful. Under the umbrella of a nursing qualification, I achieved what I believed was success in academic terms. I was both a district nurse and a health visitor before engaging in a first degree in psychology (Figure 4).

Figure 4

This degree enabled me to enter Nurse Education, where I subsequently completed a master’s degree in women’s studies that started my questioning of conventional approaches to what knowledge is, a knowledge system that appeared to exclude the meaning of the lived experience of many people whose stories lie outside the contrived world of empirical research (Figure 5).

Figure 5

A craving to be included in the academic community culminated in a doctoral study that, paradoxically, marks the end of my need to conform. All of my discomfort with received wisdom is finding solace in answers from outside mainstream evidence. The paradigm shift that I feel is occurring in the world is reflected in the shift in my own views to find solutions outside conventional approaches.

It would be untrue to suggest that the long haul up the academic ladder has been a waste of time, because it allowed me to understand how knowledge is generated and the power structures that are in place to perpetuate certain claims. Expert knowledge is socially sanctioned in a way that commonsense knowledge is usually not, and in various practices is accorded higher or lower status dependent on how it has been produced and who is saying it. These practices have as their central theme the rules of science: that is, the desire for objectivity and the defining challenges of reliability and validity. Within these tightly constrained parameters, a special language defines and delimits what is included and excluded. Therefore, at the same time as learning the rules of the research game, my own story became entwined with what I was reading and hearing, and I started to notice that the expert voices were not telling my story, a story that placed teenage pregnancy in the paradigm of abuse, as well as the rehearsed discourse about too much or too little sex education and the benefits of too much or too little contraception, not forgetting the steady moral decline that legions of young mothers were suggested to be inducing by claiming welfare benefits.

The common theme among these representations would appear to be the uniforms of belonging, belonging to nursing, to society, and to the academic community, as well as feeling right in myself. Snapshots then convey something of my truth. As Compton Burnett (1947) has said, “Appearances are not held to be a clue to the truth, but we seem to have no other” (p. 3).

Artifacts

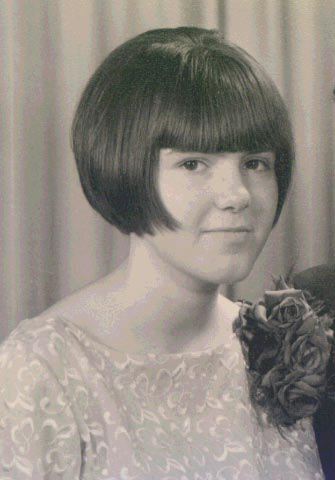

To fill some of the gaps left by the snapshots, additional evidence is supplied by meaningful artifacts acquired throughout my life, and I suggest them as a second autoethnographic technique. In the interlude between the 3-year-old and the teenage bride, school played a significant role in my life. Early school reports demonstrate the bright, capable, enthusiastic scholar with a great deal of potential. At 10, it was noted that I was “alert and lively, working diligently, producing good work, showing real promise, with obvious enjoyment and very competent” (Figure 6).

Figure 6

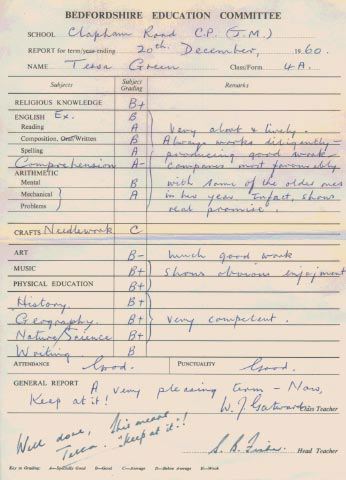

By 15, I was “not doing my best work, making little effort, lacking concentration, had a most unpleasant attitude and showing serious signs of inattention” (Figure 7) (Muncey, 2002). During this time, my childhood innocence was stolen in incestuous abuse, and the scars were etched deep within, like a black virus pervading my soul. Outwardly, I struggled, but my attention wandered with the effort, and this is what the world saw and, I thought, judged me by. A very special person wrote in a letter to my parents at the time,

I keep thinking of Tessa and how sort of semi-grown up and yet frightened she seemed at my last visit. Not frightened of any outside danger but rather aware of the changing feelings within her. Adolescence is, I suppose, the most terrible of our ages. Beyond it, safely or with scars, the adult tends to forget it, putting it out of mind the way nature has of burying the unpleasant.

Figure 7

Nobody seemed surprised when, after a very successful junior school education, I started to fail at school. Nobody asked the right questions that might have elicited the real problems. School blamed me for failing there. Family was content to let the early pregnancy be blamed on adolescent ignorance. What none of them saw was the bleak and twisted world of a girl whose self-esteem was so blighted by her experiences that the idea of a baby to care for was, in a naive way, a treat to look forward to (Muncey, 1998). My attention was drawn to a letter in a national newspaper suggesting that girls left school with babies instead of high school leaving certificates (GCSEs) because their mothers colluded with them to produce a child to fill the gap of the empty nest. The author’s name was clearly stated (Crawford, 1998). My reply, “Tale of a Teenage Mother” (1998), outlining the sentiments of my view, was anonymized despite my requesting that it not be (Figure 8). I felt this anonymity denied my voice. Although there might be questions about the use of sensitive stories in the media and in research, the challenge is how to respond to them sensitively rather than to hide them. This reaction reinforces the need for personal safety in any journey of revelation.

Figure 8

In reflecting on these artifacts, I notice a theme of power and hierarchy: the institutional power of the school, the media, and the voice of authority of an adult figure. Given the life-crushing effect of this power in my life, it is perhaps not surprising that as a souvenir of my training days, I kept the belts that signified my rising status as a first-, second-, then third-year nurse (Figure 9). As a disempowered young woman, these status symbols must have achieved a vast significance to be worthy of keeping for 32 years. The only artifact that I did not actually own was the upside-down watch, that transformative feature synonymous with the image of the nurse. At first, I could not afford one; then, I refused to have one as a small rebellion against the image of the proper nurse. This combination of rebelliousness in the face of institutional power summarizes an underlying feature of my character that might have helped me to transcend the trajectory that is seen as the customary pathway of the young mother.

Figure 9

Metaphor

Although the snapshot and the artifacts have contributed some insight into my characteristics as a teenage mother, I realize that this gives no vehicle for putting the story into a meaningful whole. On discovering the power of metaphor in writing I have done to achieve catharsis and the wonderful panoply of examples that exist in my garden, I am drawn to use metaphor in an attempt to explain my truth and to seek connections between my life experience and my academic experience.

I reach a point in my story where I am grappling with the academic world’s perception of proper research. I start to imagine that because my version does not accord with the academic and professional world, I must be a deviant case. When I started my doctoral studies, I set out to do what many researchers do: discover answers to large questions using a variety of methods to satisfy the Ph.D. examiners. At the same time, in pursuit of my personal curiosity into the explanations for teenage pregnancy, I started to take an interest into personal meanings of events and behaviors that are not generated by mainstream research, and this led me into the world of autoethnography.

Autoethnography celebrates rather than demonizes the individual story. The idea of the deviant case might be quite compelling, because it attempts to give credence to a view that does not fit in with the mainstream view and might shed some light on the “other.” However, the term deviant case has negative connotations. By the time I arrive at the point in my journey where I have to consider if my story is deviant just because no authority voice is telling it, I am left with a puzzle. Perhaps there are no deviant cases; perhaps there are just lots more individual stories waiting to be told, stories that are sometimes difficult to tell, that need support and understanding in the telling. The deviant case might be a “disconfirmation of the pattern,” as Potter (1996, p. 138) has said, but it might also be the plaintive voice of that silent minority of people whose voice is unheard (Muncey, 2002).

The puzzle over deviancy, or otherwise, of my individual case gives me further cause to reflect on how many other truths are denied. This presents a recurring philosophical idea in my patchwork life, namely, What is truth? Whose truth is valuable? Can truth vary? Is an experience true if it corresponds with the facts, or is there an absolute truth that depends on the consistency of the whole? Research has never been very successful in accepting new ideas that do not conform to received wisdom, hence the proliferation of theory to support false memory syndrome (FMS). Rather than accept the harsh reality that some women damaged by sexual abuse might be telling the truth, despite the protestations of the perpetrators, FMS conveys a powerful expert voice to silence the weakened victim. I have come to support James’s (1907) pragmatic theory, whereby a true assertion is one that proves the best for us in the long run.

My garden provides me with the evidence of the changing nature of truth. I came to see that snapshots could be deceptive, as I viewed my garden at different times of the year. The “truth” of my garden in winter is colorless, cold, and lacking growth. This same patch in summer is colorful, sunny, and prolific (Figures 10, 11). Who is to say that one is more truthful than the other? In fact, the garden has become an important metaphor for many of my life experiences. While at my first Canadian conference, I bought a book called 12 Lessons on Life I Learned from My Garden, by Glyck (1997) (Figure 12), and one of the most important in respect of the winter picture of the garden is “appreciate the growth of winter” (p. 107). In the silence of winter, all the glorious Technicolor of the summer is preparing itself, and in silence much of my most creative work emanates.

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

In a piece called the “windowsill of life,” I wrote,

I feel like a plant on the windowsill of life. Perched on this ledge I look forlornly in two directions. The darkness of the room forces me to reach to the light beyond the window and yet through the window the distance of the horizon compels me to seek the comfort of the claustrophobic room. I have never truly felt part of either world. In the dark and dingy room I struggle to find light and nourishment. Sustenance comes from the relics of a lifetime that surround me, the photos, the childish mementoes, the table around which chatter and laughter accompanied celebrations with food. In this room silence now hangs like a brittle shroud, all encompassing and yet elusive to touch. Sometimes like a menacing black cloud and at other times a companionable silence that envelopes me in its suffocating hold. (Figure 13)

Figure 13

I go on to describe myself as a plant with a virus at the core of my being that never flowers and yet survives.

Despite never quite receiving the correct balance of nutrients I put down long roots. These roots reached out into the orchards of my childhood gently entwined round each other. Just as the mistletoe depends on the tree for survival and yet deprives it of vital nourishing ingredients, I clung on to a family who appeared to care on the surface but who squeezed out the essence of my childhood. These roots gave me the strength and motivation to survive but provided no extra strength to blossom and shine.

As I found healing in nature, the foxglove came to symbolize the essence of my life (Figure 14). If you study the natural habitat of foxgloves, they grow tall and proud, every one has a unique color, and their medicinal property is healing of the heart. However, they do not grow on their own; rather, they favor the support of other plants and often prefer the shade of sheltering plants and trees. This is how I like to imagine myself: strong, proud, and unique, the heartbeat of my family growing up and under the protection of significant other people. Thus, metaphor can provide significant meaning and insight beyond the confines of isolated experiences by trying to capture the essence of the life it represents.

Figure 14

Journeys

Finally, I came to see the whole experience as both literal and metaphorical journeys. To illustrate this idea of the journey, I sought an image and found the Raven (Figure 15). As a demonstration of the synchronicity that life continues to exhibit, Raven is also the name of the narrow boat on which I live during the week to be close to work (Figure 16). In Native American medicine, the Raven is a powerful medicine that can give the courage to enter the darkness of the void and carry an intention, healing energy thought, or message, and so it seems more than appropriate to illustrate my life as a Shamanic journey.

Figure 15

Figure 16

The journey consists of stages. In the beginning are birth and the separation of the spirit from the body, the separation from innocence. Born into a family chosen for the purpose of my journey, wandering among the people of my journey, I was seeking a truth that looked and felt like me. In this early part of the journey, is also a kind of death, a separation from innocence. This is the archetype of the orphan; as an orphan, one wanders with intent, seeking the truth. This part of my journey was the longest, ending only with the realization of what my truth was. Keeping secrets is one way of protecting the truth, but it takes a great deal of energy. As I explored my self, I realized that the enemy was within me, and instead of punishing myself for being different, I could incorporate that difference into my psyche and heal myself. As I passed from warrior to healer, the important stage with respect to autobiography is the point of rebirth. At this point of rebirth, I no longer worry about the future, I know what I am becoming and that is an ancestor. The archetype of the ancestor is resolved to history, resolved to herself and the realization that life is not real until it has been told like a story (Muncey, 2002).

The starting point of rebirth in my journey was one of the most liberating educational experiences as I underwent a master’s degree in women’s studies, liberating in that here was a course actively encouraging me to take a multiperspective view about all issues. For the first time, I found people allowing me to express a view without telling me I was wrong or misguided. It was not wrong to be passionately interested in something simply because I had personal experience of it.

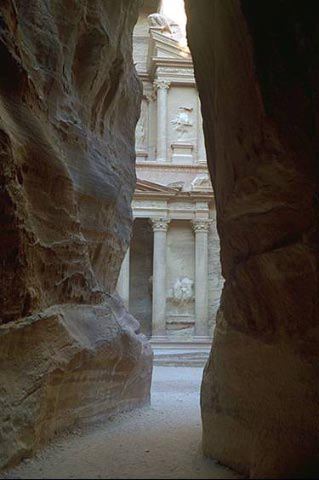

Figure 17

With newfound confidence, I traveled the world, sometimes to deliver papers at conferences and sometimes just for pleasure. In all my journeys, I examine the environment around me and find the answers to most questions in the natural setting. In Colombia, the parrots epitomize the perfect relationship, flying high and free above the parapet of the rainforest, mating for life, and beautifully disguised to fit into the natural environment (Figure 17). How arrogant of humanity to transport them alone in cages to live out miserable existences in subtropical climates. In the right time and place, all the plants and wildlife grow with abundance and a vitality that is breathtaking, and perhaps despite the lack of material possessions, there is an abundance, vitality, and self-sufficiency in the lives of the people who live within this world. In the blazing sun of the desert in Petra, I understood perfectly why the veil and abstinence from alcohol were sensible options rather than the tokens of oppression I had perhaps imagined (Figure 18). These experiences have expanded my worldview and enabled me to reflect confidently on events from differing viewpoints and to see how every experience has to be viewed in its own time and space.

Figure 18

Back from literal journeys in the natural world, I come full circle to peruse the abstract journey of research. I have likened the world of research to a superhighway (Muncey, 2002). As I reflect on my journey, I note how apt this analogy is. Superhighways are straight and dull to travel on; they have strict rules of behavior and are devoid of those idiosyncrasies that make country roads interesting. Most important, they stride across the country by passing the lived experience of all the small towns and villages, which eventually become ghostlike and neglected by lack of interest. Mainstream research appears to me to be like this, tied up in rules and conventions that make the results appear dull and flat, and ignoring completely the idiosyncrasies of the lived experience of the communities that it bypasses, so that in time, their stories become at best forgotten and at worst untold.

Journeys are about birth and rebirth, conflict and resolution, and give insight into alternative explanations and views of the world. My journeys have been both literal and metaphorical, and both contribute to the understanding of the story. Although metaphor tends to focus specifically on the experience itself, the journey represents the path of healing and enlightenment required to move beyond the experience.

These snapshots, metaphors, artifacts, and journeys makeup a patchwork of feelings, experiences, emotions, and behaviors that portray a more complete view of my life. They are useful in constructing a meaningful whole that is consistent and coherent to contribute a truth to a world that needs to hear it. A sequel to the story uncovers the discovery of a curious phenomenon. The closer people come to the objects or subjects of research, the more worried they appear to be about believing their story. My thesis is a traditionally contrived case study wherein all identity is concealed to protect those involved. However, when I talk about the results to students in my college, they become very anxious that they might know some of the participants, and this seems to interfere with the credibility of the ideas. When people are buried within the hazy world of the randomized controlled trial, distance seems to protect us from the grim reality of their lives, and somehow the “truth” of the research has a legitimacy bestowed by distance. Autoethnography is as personally and socially constructed as any form of research, but at least the author can say “I” with authority and can respond immediately to any questions that arise from the story.

Although each of the techniques might be worthy of further individual analysis, I believe that together, they have provided insight into the disjunctions that characterize this seminal experience in my life. Perhaps of all the techniques, the snapshot is the most profound. Capturing episodes of life like stills in a film, they convey the skeleton of a life without the flesh and consciousness of the being. Snapshots represent key milestones that alone demonstrate my need to belong. They portray the journey of a young girl from mother, to nurse, to academic, with no sense of the emotional or spiritual journey embedded within them. Teenage pregnancy itself might be considered a snapshot in a person’s life. It is often used as a metaphor for a society out of control. It is part of a journey that is usually deemed predictable and doomed to educational failure and poverty. The only artifact that is ever considered is the resulting child. Alone, the snapshots serve to reinforce separate aspects of success and enlightenment, but together with the other techniques, they juxtapose power and truth with the spiritual and emotional journey from victim to survivor.

The artifacts serve to highlight how power plays a part in the telling of my story, and metaphor provides the narrative technique for the journey. Snapshots can deceive, artifacts can be taken out of context, metaphor can be misinterpreted, and journeys can be reported at only the experiential level, but together, they seek to fracture the lens through which teenage mothers are usually viewed. This, paradoxically, requires them to be seen as more than the bearer of a child at a point frozen in time while acknowledging the profound impact of the event on every area of that life. In seeking to portray a new narrative to add to the received wisdom on teenage pregnancy, I hope that this multifaceted approach will demonstrate that although memories are fragmentary, elusive, and, sometimes “altered” by experience, the timing and sequencing of them is presented more powerfully in this juxtaposition of themes than if they were presented sequentially or alone. The images disguise the bewildered emotional state, the artifacts denote the need to belong and the powerful forces that prevent this, the journeys demonstrate that although the event was a defining moment it is not the end of the story, and the use of metaphor enabled me to get to the core of the experience and write about it in a way that is both understandable and cathartic.

References

Brookes, I (Ed) (2003). The Chambers dictionary. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap.

Compton Burnett, I. (1947). Manservant and maidservant, a god and his gifts. London: Gollancz.

Crawford, M. (1988, March 19). Why teenage parents are about low expectations [Letter to the editor]. The Guardian, p. 17.

Ellis, C., & Bochner, A. P. (2000). Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity: researcher as subject. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 733-768). London: Sage.

Fischer, M. (1986). Ethnicity and the post-modern arts of memory. In J. Chifford & G. E. Marcus (Eds.), Writing culture: The poetics and politics of ethnography (pp. 194-233). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Glyck, V. E. (1997) .12 Lesson on life I learned from my garden. Emmaus, PA: Daybreak.

James, W. (1907). Pragmatism. London: Longman.

Kierkegaard, S. (1957). The concept of dread (W. Lowrie, Trans.) Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

King, C. (1992) The politics of representation: A democracy of the gaze. In F. Bonner, L. Goodman, R. Janes, & C. King (Eds.), Imagining women: cultural representations and gender (pp. 131-139). Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Kuhn, A. (1991). Remembrance. In J. Spence & P. Holland (Eds.), Family snaps: The meaning of domestic photography (pp. 17-26). London: Virago.

Muncey, T. (1998). The pregnant adolescent: Sexually ignorant or destroyer of societies values? In M. Morrissey (Ed.), Sexuality and healthcare: A human dilemma (pp. 127-158). Salisbury, UK: Mark Allen.

Muncey, T. (1999, February). Autobiography as polemic. Paper presented at the Advances in Qualitative Methods conference, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

Muncey, T. (2002). Individual identity or deviant case. In D. Freshwater (Ed.), Therapeutic nursing (pp. 162-178). London: Sage.

Potter, J. (1996). Discourse analysis and constructionist approaches: Theoretical background. In J. T. E. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative research methods for psychology and the social sciences (pp. 125-140). Leicester, UK: BPS. Retrieved March 29, 2005, from http://www.lboro.ac.uk/departments/ss/depstaff/staff/bio/JPpages/Richardson%20Handbook%20Chapter%20for%20web.htm

Russel, T. (1998). Auto ethnography: Journeys of the self. Retrieved August 8, 2004, from http://www.haussite.net/haus.0/SCRIPT/txt2001/01/russel.html

Spence, J., & Holland, P. (1991). Family snaps: The meaning of domestic photography. London: Virago.

“Tale of a teenage mother” [Letter to the editor]. (1998, March 23). The Guardian, p. 17.

Tedlock, B. (2000). Ethnography and ethnographic representation. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 455-486). London: Sage.

Tierney, W. G. (1998). Life history’s history: Subjects foretold. Qualitative Inquiry, 4, 49-70.

Warner, M. (1994). Six myths of our time: Managing monsters. London: Vintage.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical investigations. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (1) March 2005 |