“My Way”: Piloting an Online Focus Froup

Jennifer Oringderff

Jennifer Oringderff, MBA, Doctoral Candidate, The Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland

Abstract: In this article, the author outlines a method of online data collection. The pros and cons of using online focus groups to collect information from a geographically diverse population are discussed.

Keywords: data collection, internet research

Citation Information:

Oringderff, J. (2004). “My Way”: Piloting an online focus group. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(3). Article 5. Retrieved INSERT DATE from http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/3_3/html/oringderff.html.

Although some researchers have analyzed individuals’ use of the web as a communication and/or information-gathering tool (such as chatroom discussions or listserv postings), the web is more commonly used for the collection of secondary data and/or market research. Online focus groups (OFG) are an emerging qualitative method that enable researchers to capture primary data from a geographically dispersed population. I have been piloting online focus group discussions for the last 12 months, and the experience has allowed me to identify important advantages and disadvantages that have yet to be addressed in the methods literature. There were days that the OFG was the bane of my existence as I tried to iron out clashes between participants or attempted to stimulate discussion across multiple time zones. But overall this method provided an excellent forum for capturing information from places and people that I could not reach in any other way.

“Regrets? I’ve had a few...”1

The words of Ol’ Blue Eyes (Frank Sinatra) encapsulate my reflections on my experiences running an OFG. Unfortunately, little has been written about using online focus groups in academic research, so much of my work was “trial by fire”. Fortunately, I have learned from my mistakes and can share them with you, so you won’t have to make them as well!

Several factors conspired to lead me to use an OFG. My most recent project examines the effects accompanying expatriate spouses have on the success of an international assignment; in the initial stages, I felt a focus group would be an excellent way to get a sense of the issues confronting these individuals. However, the challenge of conducting a focus group with this population meant that I had to find a way to bring participants together from around the globe and across time zones, and bearing in mind their differing English-language and technology skills. Having neither the time nor the resources to organize face-to-face meetings of my sample group, I had to find a way to meet in the virtual world. I was familiar with online focus groups used for market research and wondered if this approach might work. As I started perusing the literature, in both my own area and in a more general (i.e., desperate) search, I came across very little that addressed the use of online focus groups in academic studies. Despite this lack of guidance as to proper procedures and/or the benefits and limitations of the method, I was convinced that an OFG was the way forward so I pressed on!

“Yes, there were times, I’m sure you knew

When I bit off more than I could chew”

There are two main types of OFGs: synchronous and asynchronous. Synchronous focus groups are similar to traditional face-to-face focus groups as they feature real time interaction between the moderator and participants, but use chatrooms or focus group software packages instead of real classrooms. However, these are very difficult to manage if participants are in different time zones. Also, most free software packages do not save transcripts, so the moderator must find alternate means of recording interactions. One benefit is that the initial reactions and opinions of participants are more spontaneous in real-time interaction, which may give researchers more reliable results.

In asynchronous groups, participants log in and answer discussion topics on their own time, through listservs, mailing lists or discussion groups. Benefits include the ability to overcome global time differences, time allowances for participants with variable typing skills, and more time for participants to focus and reflect on responses.

Whatever type of OFG you use, benefits abound! There are no stringent time limits, so a focus group can run as long or short as required, and groups can be assembled and disassembled quickly. OFGs are less expensive to run and can often be conducted using free or inexpensive software.

As for sample size and selection, many more respondents can be included because the online environment is not affected by size of the group. Also, wider geographical access is possible because the internet is available in urban and remote locations.

Use of an OFG can also produce in-depth, rich responses, especially in asynchronous environments. And, when the software captures real-time discussions, there is no need to manually transcribe the session. This not only saves time but also enhances accuracy in the written transcripts.

OFGs can also be more appealing to participants. Researchers can ‘sell’ involvement by emphasizing that there is no need for participants to leave their home or office, and (in an asynchronous format) participants can respond when it is convenient. These freedoms may persuade some individuals to participate who normally would not, especially due to work-related scheduling problems (be they stay-at-home parents or oil platform workers). Subjects who might feel uncomfortable revealing themselves for political, religious, or social reasons might be more inclined to participate in an online environment where their anonymity can be protected though this may require the moderator to set anonymity features in the software package. Finally, the online environment can offer social equalization as individual socio-economic status, ethnicity, nationality and gender (all potential issues of contention in a face-to-face setting) may be unknown to other participants and can therefore serve as an egalitarian method of data collection.

There are several disadvantages to OFGs that must be carefully considered when planning a project. Recruitment can be difficult for many reasons, such as limited access to specific populations and a disinclination to participate. Also, participation hinges on respondents’ computer access. Creating and moderating a group can be time consuming if all aspects of the process are not carefully thought out in advance. And, the role/skill of the moderator in managing the discussion is crucial to the efficient operation of the group and must be carefully considered when devising the OFG structure.

Several limitations exist in the area of group dynamics. Lack of nonverbal cues and the absence of vocal cues (e.g., inflection and intonation) can have a negative effect, as offense may be taken more easily and meanings misconstrued. Further, an online environment sometimes affords individuals more freedom of expression (and therefore less discretion and tact). Conflict may flare up as a result of inflammatory language (especially with sensitive topics), and this can alter participant interaction. There is also the tendency for participants, particularly in a group that evolves over a period of time, to develop ‘pair friendships’ where they engage in their own exclusive dialogue and alienate the rest of the group.

Technological issues such as online security and authentication of participant identity must also be considered, as not all computer environments are created equal and some are more susceptible to hacking. Also, strategies must be employed to attempt to verify the authenticity of participants as much as possible while still preserving anonymity. To some degree, you can vet potential participants for authenticity by asking a series of questions to which only suitable candidates would be able to respond. In my case, I asked questions about treatment by sponsoring organizations and terms of expatriate contracts. Most people who do not actually fit the criteria will not take the time to respond falsely to such specific questions, and, even if they do, it is usually easy to pick them out. While this does not provide total security, it is a start. Moreover, when participants choose to use an online pseudonym, their identities are doubly protected once by the anonymity of their online identify, and a second time by the researcher’s call for confidentiality.

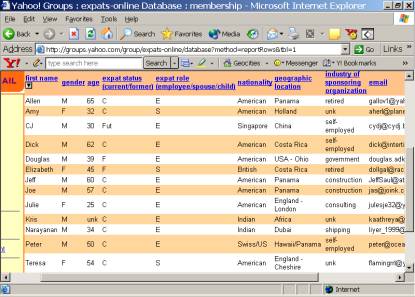

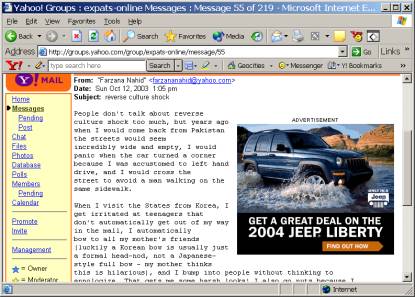

I created an asynchronous OFG called ‘Expats Online’ that was designed to serve as a brainstorming forum for a community of international expatriates about the issues they faced when relocating to another culture. I used Yahoo’s free discussion group service to create the group, and then posted invitations to join on other expatriate discussion groups and web sites. Interested parties applied for membership and were approved for membership if they met my inclusion criteria (e.g., age, marital status, employing industry, etc.). Information was provided both in the initial invitation and in the FAQ of the online group as to the purpose and rules of the group. To initiate discussion, I posted a message to all participants raising an issue. Participants went to the message board periodically and contributed to the discussion threads. Multiple themes ran at the same time and participants could contribute as much or as little to each thread as they wished.

Before undertaking on online focus group, it is imperative that the researcher consider the logistics and limitations of this type of technology and the attitudes of potential participants. As a result of my experiences operating an asynchronous OFG, I have developed the following ‘best practice’ guidelines to warn other researchers of the issues they need to consider:

1. Bring together participants who are comfortable participating in an electronic medium.

If some members of the group are not familiar or comfortable in on online environment, their participation will be greatly deterred. Also, if participants are not aware of ‘netiquette’ (e.g., the notion that typing in ALL CAPS can be considered AGGRESSIVE!), problems can ensue.

2. Make procedures clear, and make sure they are followed by moderator and participants.

Be sure to set up a FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) to inform participants of the rules of the road and be consistent and vigilant about adhering to these. For example, I said that I would not allow postings that advertised other online groups (this is very common in online discussion groups it’s like online networking). One member kept posting about a group she ran, and I let it go because the group was topically related to mine. However, when another member began posting about an unrelated group, I posted a warning reminding him of the FAQ against this practice. He (and several others) were quick to point out that I had allowed the other member to advertise her group several times. This situation hurt my credibility as a moderator.

Figure 3. A sample of the message list. Please note that all participants agreed to have their screen names used in research publications.

3. Choose a capable and knowledgeable moderator.

If you cannot devote time to monitoring a discussion that is occurring across multiple time zones, recruit (and train) someone else to moderate the group. If you only visit the group every 12 hours, for example, a lot may happen while you’re offline both negative and positive and the dynamic of the group could be changed.

4. Consider how and where you’re going to find participants.

Compile a list of related web sites and discussion forums you can use to post messages about the creation of your group. But don’t assume that individuals replying to your solicitation are the respondents you want. In my case, I posted invites at several related discussion groups, but I still asked interested respondents to provide me with demographic details to see if they matched my inclusion categories. Although a respondent can fabricate details, they are less likely to do so when faced with giving specific information because they don’t know exactly what you’re looking for.

5. Keep the discussion focused.

Participants tend not to treat an online environment as formally as they would a face-to-face group. Therefore, discussion sometimes wanders to unrelated topics. This is again why it is necessary to have a moderator on hand most of the time to keep the discussion on track.

6. Make time limitations clear.

If you only intend to run the group for a set period, be very clear about what will happen when the study is complete. In my case, I intended to run the group for three months, and then shut it down. While I made it clear that the group would only run for this period, I did not tell the participants I would be limiting access after that time. Many participants had developed relationships with each other and I got many angry emails asking how they were meant to contact each other once I had terminated the group. I could have avoided this by making clear that access would be denied after the time frame had elapsed.

“The record shows I took the blows and did it my way!”

While you certainly don’t have to do it ‘my way’, chances are you may be able to employ some of the tips and guidelines I have mentioned here in designing your own OFG. The potential benefits are numerous and the limitations are manageable. If you are dealing with a geographically dispersed, difficult-to-access population, an OFG could be just what you’re looking for.

Edmunds, H. (1999). The focus group research handbook. Lincolnwood, IL: NTC Business Books/Contemporary Publishing.

Gaiser, T. (1997). Conducting on-line focus groups. Social Science Computer Review, 15: 135-144.

Jones, S. (Ed.). (1999). Doing internet research: Critical issues and methods for examining the net. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mann, C. & Stewart, F. (2000). Internet communication and qualitative research: A handbook for researching online. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Murray, P. J. (1997) Using virtual focus groups in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 7(4), 542-54.

Newhagen, J. E. & Rafaeli, S. (1996) Why communication researchers should study the internet: A dialogue. Journal of Communication, 46(1), 4-13.

1. Lyric excerpts throughout article from:

Anka, P., & Sinatra, F. (1969). My way [Recorded by F. Sinatra]. On My way [compact disk]. Los Angeles: Reprise Records.