Overview of the immigration history of Alberta's German-speaking communities (Part 2: 1918 to the present)Regaining confidence and status

After the War, it took several years for the German-speaking community in Alberta to become visible again in society at large. German social clubs slowly re-established themselves and put much emphasis on providing aid to the newly arrived immigrants from Germany. From ca. 1923 on, there were calls in the community for a re-awakening of a German ethnic consciousness and pride, and some people made demands for "equal rights" for the Germans in Alberta. In 1925 and 1926, there were frequent reports in the press about the accomplishments of "the Germans" in Alberta. The resurgent immigration by Mennonites was welcomed by many spokespersons for the German-language community as it would increase the German presence in the province. Efforts to organize the Germans to speak with a common voice made slow progress.

In 1927, relatively large-scale immigration from Germany was permitted again, prompting some people again to issue strong calls for the "equal treatment" of Germans. The German-language newspapers published reports on how respectfully the Germans were treated in other countries around the world; demands were made for more German language instruction in public schools, for more public visibility and more government jobs for speakers of German. The first German Days in 1928, held in Edmonton, had been planned as a social event, but were also intended to raise the Germans' self-confidence in society at large. More German clubs were founded and flourished. But there were clouds on the economic horizon, and people started to worry about immigration from Germany; the beginnings of the impoverishment of immigrants could be seen everywhere. By 1929, more Mennonites and other settlers arrived in Alberta, and for 1930, more Mennonites were expected in Canada, destined mostly for Alberta's North. Some Germans were loudly looking for their "place in the sun." German Days and various folkfests and sportsfests did indeed contribute to developing ethnic pride and confidence, and English-language media reported favourably on the Germans. In view of the economic difficulties, German-speaking labourers attempted to organize themselves politically, but with comparatively little success. Eventually, Canada closed its door to immigrants, and even local Germans asked themselves whether more immigration would really be a boon for the German group in Alberta. The issue of whether or not it was possible to show "double loyalty" (politically, to Canada, and, culturally, to one's German heritage) was raised repeatedly and defended.

In 1931, the German Days became more political in nature, emphasizing the greatness of German history and German character, and publicizing and praising the accomplishments of the Nazi state to a rather apolitical and therefore apathetic audience. Yet speakers continued to reflect on the German-Albertan identity and what it meant in the context of the "Deutschtum im Ausland." The 1932 German Days were another huge success; more and more German cultural activities were available in the community than ever before, reflecting the growing self-confidence of the German-speaking community.

The club life certainly could be lively. Clouds on the horizonAfter Hitler's rise to power in 1933, many German-Albertans initially defended the "New Germany" and rejected with disbelief reports on crimes against Jews in Germany, but German-Jewish relations in Alberta were generally good, and as more and more reports on Hitler Germany's crimes were reported in the English-language media, public support by German-Albertans for the Nazis dwindled drastically. Between 1934 and 1937 there was a strong increase in German cultural activities, and the "Germans" were generally well regarded in society. In 1936, there was a major controversy in the German-speaking community and the anglophone community at large about the appropriateness of flying the swastika at German Days and playing the Horst-Wessel-Lied. Many German-Albertans voiced complaints about discrimination and agreed with stronger demands for equality, but they insisted that they were loyal Canadians, and "O Canada" was played next to the German anthem. Beginning in September 1938, suspicions (totally unfounded, as it turned out) surfaced in the English-language media that German-Canadian organizations, such as the Deutscher Bund, and even Nazi spies were infiltrating and undermining the law- abiding, loyal German-Canadian groups in Alberta and, of course, Canada's institutions. Many German-Canadians resented these allegations as an unfounded defamation of their group. Nevertheless, anti-German feelings intensified. Several German-language papers that strongly supported the Nazi cause defended the community against "unjustified" accusations and proclaimed the German-Canadians' loyalty to Canada. Even so, the rift between some German clubs and organizations and the more politicized groupings widened, and attendance at the now highly politicized German Days suffered a drastic decline. War, againAt the beginning of the War, internment camps were swiftly established, and members of certain German-Albertan groupings were quickly rounded up and interned. By the end of 1939, towns and cities all over the province were purging their employment rolls of Germans. On the other hand, many German-Albertans were ready and eager to fight the Nazis. In the spring of 1940, a controversy arose about a social studies textbook approved for and in use in Alberta's schools which was considered to be "too soft" on the Germans. Various patriotic organizations proposed strict measures against the Germans, and public hysteria about a possible threat of "fifth-column activities" in Alberta by German-Canadians (never proven) aroused the public mind. For the remainder of the war, German-Albertans had no public profile whatsoever as German clubs suspended their operations. Once more, a vibrant German community

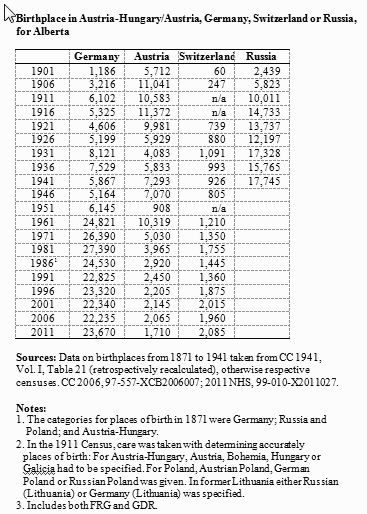

From 1947 on, "German" immigration resumed, first by the Volksdeutsche [57], and over the years restrictions on immigration from Germany itself were gradually eased. Tens of thousands of immigrants who were born in Germany, Austria or Switzerland poured into Alberta. The number of Albertans with German mother tongue increased from 48,000 in 1946 to 65,000 in 1951 and reached its highest number ever in 1961 with 97,666 persons. From 1951 on, German clubs and organizations were slowly

In the mid-1970s, a strong increase in the public visibility of the German-Albertan community, encouraged by the policy of Multiculturalism, led to greater public confidence and display of ethnocultural pride. German-language shows appeared on radio and television. The German stores in the Whyte Avenue area in Edmonton and elsewhere teemed with German-speaking shoppers on Fridays and Saturdays; the clubs competed with each other in the number of musical, sports, and social events offered. Thousands of students from German-speaking families were registered in schools and universities. The German clubs endowed scholarships in schools and universities to motivate students to learn German, and a new English-German bilingual program—at first watched with suspicion by the private German language schools—developed a new breed of fluently German-speaking children. Formal balls in Edmonton and Calgary became the high points of the social calendar, and Alberta became very attractive for investment from Germany. Locating a Consulate General of the FRG in Edmonton underscored the importance which Germany attached to close relationships with Alberta.

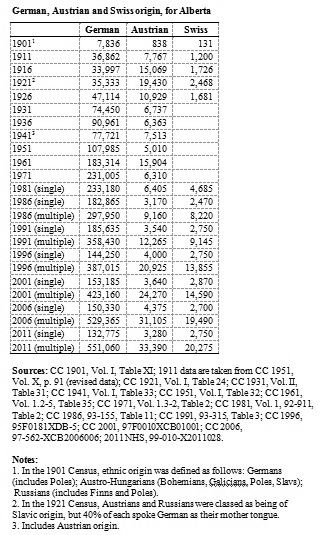

Sampling the life of Alberta's German-speaking communities in the 1980sThe following table shows the numbers of Albertans claiming German, Austrian, or Swiss origin in the Canadian censuses since 1901. According to these data, there were 153,185 Albertans claiming German ethnic origin in 2001; another 423,160 persons reported having "German" as one of their ancestors' origins. But these numbers are misleading: Since the definition of "ethnic origin" refers to the "ethnic or cultural group(s) to which the respondent's ancestors belong," the respondent may in fact have virtually no contact with "German" except having a great-grandfather of German ethnic origin who immigrated from Russia 100 years ago.

In spite of this caution, it is obvious that the number of Albertans having German origin nevertheless is substantial. It is not surprising therefore that there were (and still are!) numerous German clubs and other groups in the Province of Alberta fulfilling cultural and social functions. The German-Canadian Association of Alberta, the umbrella organization for most German clubs and associations in the province, listed 26 groups as its members in the January 1986 edition of the Alberta Echo, its official publication. But in addition, there were groups which were not members of the German-Canadian Association of Alberta, and although most clubs and associations were (and are) located in the major centres, German clubs were located in other regions of Alberta as well, for example, in Fort McMurray, and Hinton—in short, between 40 and 50 German clubs in Alberta ministered to the socio-cultural needs of the German-speaking communities in Alberta in the 1980s. For example, every year the Edmonton Karnevalsgesellschaft Blaue Funken organized a Prinzen-Galaabend, which, in the tradition of the carnival celebrations of the Rhineland, was always a smashing success. Club Austria sponsored about one Weinkost each month (with the major event in celebration of good wine taking placing in the fall) at which new and old wines from Austria could be sampled by real and self-styled connoisseurs alike in a gemütliche atmosphere. But there was a great deal more to do. The Calendar of Events in the Alberta Echo, during the 1985 calendar year, drew attention to more than forty major events which were to take place in Edmonton, among them theme dances, presentations by ethnic choirs, bands, and dance groups, ethnic festivals, and meetings of various ethnic interest groups. A similar range of activities was available to club members and the public at large in other areas of Alberta, such as Calgary and Red Deer. And, of course, there were the annual Deutsche Tage, a celebration of ethnic food and drink, sports, entertainment, and games for the children.

For persons who preferred their culture with a capital "C", the city of Edmonton was the location of two Viennese-style balls in the classical tradition. Both were fine entertainment and drew local as well as Austrian dignitaries, and both were, in the final analysis, dedicated to a charitable cause: funds were collected for scholarships to enable talented students to study music in Austria. During the academic year at the universities, the discriminating listener was able to attend free recitals given by advanced music students as part of their examinations where German composers of lieder play a very important role. And, of course, there was always a German component to be found in the music programs of several local AM and FM radio stations as well as on the programs of the symphony orchestras and operas (examples being Wagner's "Lohengrin" and Mozart's "Zauberflöte" and "Die Lustige Witwe" in Edmonton, and "Die Fledermaus" in Calgary and Edmonton). Once in a while, the Studio Theater at the University of Alberta and the Citadel Theater performed plays, in English, by Brecht; several lectures on German literature were given each year by professors at the University of Alberta and the University of Calgary, and visiting professors were invited to give such lectures at the major universities in the province. Those who did not find these cultural highlights to their taste had a number of other avenues open to them to get their entertainment in German. Until 1984, Studio 82 on Whyte Avenue in Edmonton showed popular movies from the 1950s and 1960s which appealed particularly to the older people of German origin. Subsequently, films such as "Wetterleuchten über dem Zillertal" or "Jugendstreiche des Knaben Karl" were shown in Zeidler Hall in the Citadel Theatre. In Calgary, the Plaza Theater screened these old films about twice a month. The Beverly Cinema in Edmonton, for a while, showed German feature film classics as well until the public began to lose interest. In Edmonton, other local movie theaters (for example, the Princess and the Varscona), the National Film Theater, the Edmonton Film Society, as well as the Department of Germanic Languages at the University of Alberta, showed a variety of German films on a more or less regular basis. In Medicine Hat, it was reported, Heimatfilme were shown quite frequently for the members of the older generation. German-language newspapers, magazines, and radio and television programs enjoyed considerable popularity in Alberta over the years. A checklist of German-Canadian periodicals contained seven general-circulation newspapers, four club newspapers, and 27 church bulletins which have been published at one time or another in Alberta. [58] In 1986, there were two German-language publications available in the province, the Kanada Kurier and the Alberta Echo, both having a circulation of more than 3,000 copies in Alberta. A very popular service to the German community of Edmonton was the "Lesezirkel Zimmermann," an agency from which one could borrow, for a small weekly fee, a number of women's and news magazines as well as the mass-circulation illustrated papers published in Germany. In the broadcast media, "Forum in German," for a while, was the only show in town, in Edmonton, that is. The producer responsible for this half-hour television show, which came in with the advent of cable television in Edmonton, attempted to put together a show which would please many tastes, and presented a variety of programs ranging from TV games to interviews, song recitals, and choir performances. The show required sustained input from volunteers in the German community in Edmonton, and after seven years of struggling against the odds, "Forum in German" ceased broadcasting in 1981. The Edmonton cable TV company QCTV offered a short program, "The German Scene," for several years, with material provided by the Consulate General of the Federal Republic of Germany. In Calgary, the community TV channel presented a weekly show, Das Ahornblatt, as well as a broadcast originating from Red Deer, Ein erfülltes Leben. Air-time was also used for German on educational television. The beginnings of what today is an Alberta-wide network of educational programming go back to 1970 when the Metropolitan Edmonton Educational Television Association (MEETA) began distributing programs via Channel 11, sharing air-time with the CBC French network. The educational network broadcast in English between 9 A.M. and 3 P.M. and between 7 P.M. and 9 P.M., but included a number of German programs obtained from the film library of the local German Consulate. These were primarily documentaries on scientific achievements, environmental protection, biographies of famous German personalities, and cultural events and a few music programs. In 1971, the German language instruction series "Guten Tag" was acquired and aired twice in the schedule, and it was repeated in the following year. In 1973, the more advanced series "Guten Tag—Wie geht's?" was broadcast for the first time. Accurate user statistics were not available regarding the number of persons actually watching the German program, but some 500 program guides for the first series were sent out in response to audience requests. German on the radio has a long history in Alberta; as early as the 1920s, the Young Men's Bible class (Baptist) started broadcasting the Gospel in German over the radio. It was reported that "the response from many scattered settlers hungry for the word of God and homesick in a strange country was beyond expectation. Some drove for miles and gathered round a radio for this half-hour service in their mother tongue." [59] After World War II, the Lutheran Church put on a Lutheran Hour on the radio, which was called a resounding success because it helped dispel some of the suspicions which Canadians had of the Germans at that time. [60] During the years of the immigration boom from Germany after the War, a certain Rev. Freytag sought to serve immigrants with informative 10-minute German language talks on CKUA radio. [61] In the 1980s, German on the radio was heard for entertainment as well as spiritual edification. In Edmonton, CKER brought its German listeners in Edmonton an afternoon German show since its founding in November 1980. The music part of the show was structured so as to please a large segment of the German-speaking population of Edmonton and vicinity: traditional folk songs, light classical music, and modern pop music. A very important part of the show were cultural materials supplied by Internationes and by radio stations in the Federal Republic of Germany, which focussed on cities in Germany, seasonal customs and traditions as well as social and political events in the Federal Republic. Interviews with local and visiting luminaries as well as chats with ordinary visitors to Edmonton balanced out the program. Every day at 5 P.M., the station broadcast news from Germany taped via the telephone from the German Press Agency in Bonn, and for a number of years, brought the news from Austria and from Switzerland as part of the weekly broadcast calendar. And, last but not least, a sports report was broadcast twice a week to keep listeners up-to-date on what was happening, for example, in the German soccer leagues. In Calgary, CHRB offered the German show Heimat-Melodie—Das Grosse Wunschkonzert on Sunday afternoons from 4 to 6 P.M. For the faithful, several radio stations (for example, CJOI in Wetaskiwin and CKER) broadcast radio sermons in German on Sundays as well as weekdays. Of course, anyone owning a shortwave receiver did not have to wait for the 5 o'clock news on CKER; he could simply tune in to any one of the frequencies used by the Deutsche Welle, the German short-wave service, the reception of which—depending on the time of day, quality of the receiver, and the status of the sun spots—was as clear as a bell or just so much static. For two years, the University of Alberta (financed by a grant from the Consulate General of the Federal Republic of Germany) made available daily news recorded from the broadcasts of the Deutsche Welle over a local telephone number—which, as this service was available before CKER began its operations—logged as many as 93 calls per day. For several years, one half of the city of Edmonton was able to receive Deutsche Welle broadcasts over their cable connection, weather conditions permitting. There is no doubt that local businesses owned by "Germans" appealed to the members of the German community for their business: A person reading the Alberta Echo of January 1986, for example, could find 76 services and businesses advertised and do virtually all his shopping in German in Edmonton and vicinity. The Kurier of the same period, in its Alberta section, drew the reader's attention to a similar range of services and businesses in Edmonton and Calgary, and most larger and smaller communities in Alberta had their share of German-speaking shops and businesses. In all of Alberta, about seventy churches offered services in German at least once a month (some even twice or more often each Sunday) in the 1980s. In Edmonton, a person wanting to attend a service in German would find eleven churches advertising such services in the Religion section of the Edmonton Journal and the Kanada Kurier. In Calgary, according to the Kanada Kurier of the same date and the Calgary Herald, six churches offered services in the German language in January 1986. Heady days, the 1980s, for Alberta's German-speaking communities! The German-Albertans: Becoming an invisible minority?In spite of the ostensibly flourishing cultural scene in the 1980s, German-Canadian organizations became increasingly aware of the need to appeal to and attract the younger generation and therefore supported a number of appropriate measures. Social clubs across the province invited many different dance and music groups from Germany and Austria to their festivities. German-Canadian groups, such as the German-Canadian Congress, became active on a national scale, but met with limited success in Alberta. Their desire for survival encouraged the German-Albertan groups to collaborate and reach out to other ethnic groups and to the community at large, and to develop strategies for sociocultural development. In the 1990s, government policy shifted from preservation, maintenance, and development of the ethnic heritage to facilitation of integration and a fight against intolerance and discrimination. Less government funding was available for virtually all projects undertaken by the ethnocultural groups, forcing a retrenchment and a re-deployment of efforts. Public attention shifted to more recent immigrant groups, and the German-speaking cultural groups, like others, began to "suffer" from benign neglect. While many smaller German clubs were wondering about their continued survival, immigration from the German-speaking countries reached very low levels (for instance, 185 persons from Germany in 1995, 75 from Switzerland and 19 from Austria) and could not provide for replenishment of the pool of German speakers. More and more German-run stores closed, and the public profile of the German-speaking community in Alberta began to decline. From the multitude of events organized by German-Canadian groups described above, the reader might get the impression that all is well with German language and culture in the Province of Alberta. Judging from the large number of Albertans of German origin—some 153,185 according to the 2001 census who gave German as their only origin and another 423,160 who listed "German" as one of several ethnic origins—and German clubs, associations and choirs in Alberta, there should be a strong and lively interest in the events organized by them. The picture is deceptive, however. It is indeed true that, at present, German ethno-cultural and social events are still reasonably well-attended, but the emphasis must be on "still." According to most community leaders, presidents of German clubs, newspaper editors, language school teachers, and ministers, the interest expressed in the activities offered has, at best, remained stable or has slowly but steadily declined. In particular, it is the young people of German origin who are not participating. According to the president of one of the major associations, the social and cultural events sponsored by most clubs (except those which offer sports entertainment) are attended predominantly by the first generation, the immigrants for whom German is the mother tongue. He estimated that less than one percent of the young people of German origin (the second and third generations) is involved in organized ethno-cultural activities. The Kanada Kurier apparently was read (until its recent demise) primarily by older people. In the churches—if services are still held in German at all—it is the very young children and the members of the immigrant generation who appear to attend most frequently. Obviously, these are generalizations; in churches where an effort is being made to attract the children by a youth program or a language school, the percentage of youngsters is sizeable; no doubt, there are a few members of the second generation who until recently read the Kurier—and now read the Albertaner—regularly and listen to German programs on the radio. The German-Canadian Cultural Center in Edmonton always draws large crowds for its events, and its library houses a wealth of books and videos for children and adults alike. The German-Canadian Business and Professional Association is a vibrant and active organization, and the Austrian and German clubs in Calgary as well as in Red Deer and other large centers are still centers of attraction for folkloristic and social events. But the trend is undeniable: quite often, the comment may be heard that in perhaps twenty years there will not be much left of most of the German clubs and associations. Although some Canadian-born Albertans from German-speaking families speak German fluently and correctly, English has become the first and dominant language for most young Albertans of German origin. In terms of the proficiency in and formal knowledge of their parents' mother tongue, German for them is now a distant second language, barely understood and hardly spoken. It seems that "the Germans," wherever they may be from, have become an "invisible minority" in the everyday cultural life of the community. Only on certain holidays and festival days do some of them get together and talk and behave "like Germans." For them, German language and German culture have assumed the role of museum pieces to be displayed exuberantly and publicly when the occasion warrants it; at all other times, however, they take pains to show that they have been acculturated to the mainstream "Canadian way of life" and to Canadian social expectations. One of the reasons for the lack of participation among the majority of young people of German origin might well be what has been referred to as a "museum approach to German culture": to cherish and preserve aspects of German culture (folk dancing, folk singing, wearing folk costumes) which have become "petrified" in North American society while they are on the verge of extinction in Germany—aspects which, for better or worse, have little relevance in present-day German culture, at least to the young people who have grown up in Canada. To many Albertans, the concept "culture" is synonymous with food and folk dancing, and the Alberta Heritage Days reinforce the perception that, for "typical" German culture to be enjoyed, the visitor has to eat a Bratwurst mit Sauerkraut, followed by a slice of Apfelstrudel, while watching a performance of Schuhplatteln or listening to a group of enthusiastic Jodler. To be sure, these aspects are significant and enjoyable dimensions of traditional German culture, but presumably there is more to German culture than eating, drinking, and dancing "in the old style"—and yet there is little that is offered in terms of contemporary German, Austrian, or Swiss culture, be it a discussion of contemporary life styles, the value system, entertainment, or the arts. Only schools and universities attempt to convey to the learner a view of the culture of the German-speaking countries as they exist today, in all their similarities and dissimilarities with North American culture. Visitors from Germany are frequently surprised at the opinions and attitudes held by some of the "old-timers" (i.e., those who immigrated some forty years ago) and will tell them that "things just aren't like that any more." It is a well-known fact that emigrants tend to preserve a perception of their home land "the way it was then," especially if they feel that modern ideas and attitudes—be they political, social or economic—are not an improvement on what they used to know and maybe like. Small wonder then that the younger generation, which is mobile and often can readily afford to travel to Europe, will reject ethno-cultural activities that they consider to be outmoded curiosities. |