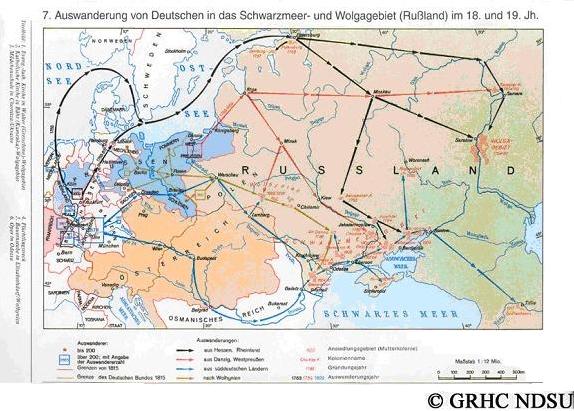

The Germans from Odessa and the Black SeaDefinitionThe group of settlers commonly referred to as "Germans from Odessa and the Black Sea" were immigrants from western and southern Germany (followed later by Prussian Mennonites and Swabians) who settled on the northern coast of the Black Sea between Odessa and the Caucasus. They followed the invitations extended by Catherine the Great and Tsar Alexander I. to colonize large areas of Russia. History [1]The history of the Black Sea Germans is more than 200 years old. At the end of the 18th century, Russia conquered in the war against the Turks vast areas of the steppe by the Black Sea, the cultivation of which was to be implemented immediately. As serfdom limited the Russian peasants in their freedom of movement and thus made an immediate settlement of the new area impossible, foreign settlers were recruited. In July 1763, Tsarina Catherine II. issued in a manifesto the permit to all foreigners coming to Russia to settle in gouvernements of their choice and granted them special rights. The Tsarina's manifesto also guaranteed foreign settlers the right of free religion and self-government aside from various economic and political privileges. Her call was most welcome in the German small states where economic hardship, denominational differences, and wars had suppressed the population.  Source: http://www.lib.ndsu.nodak.edu/grhc/history_culture/history/images/pic7.jpg Tsar Alexander I. was determined to continue the colonization politics in South Russia begun by Catherine. Based on the colonization program drawn up by the Secretary of the Interior, the gouvernements of Cherson, Jekaterinoslav and Taurida were settled, and as of 1812 also Bessarabia. In 1803 the first settlers from the town of Ulm arrived via the Danube at the quarantine ward of Dubossar, and in the spring of 1804 the distribution of land got started. The decree for the colonization by foreigners provided for the distribution of large connected tracts of land at good sites. German colonies in the Odessa RegionIn the beginning, the unfamiliar geographic and climatic conditions created great difficulties for the German farmers. They were forced to develop new methods of land cultivation and mainly raised cattle in the first phase of their adaptation to these new circumstances. In 1805, sheep with fine wool were brought to the cities of Odessa and Dnepropetrowsk and the breeding of these animals began in New Russia. This wool was soon the colonists' most important product. The Germans also managed to adapt East Frisian cattle to the adverse conditions of the steppes. Later the colonists began to extensively grow grain, sunflowers, wine, vegetables, fruits, tobacco and silk. They worked as beekeepers and in forestry. There were brickyards, wineries, breweries, cheese factories and oil mills in many colonies. Soon water-, wind- and steam-powered mills, stud farms and cloth factories emerged. [...]

Map of Glückstal District, Cherson. Source: http://www.rollintl.com/roll/gluckstal.htm The colonies of GroßliebentalOverall, more than 500 colonies were founded in present-day region of Odessa east of the Dnjepr River and approximately 40 in the area of Nikolajew and approximately 150 in Bessarabia. The colonists often named the villages after their home towns. Thus, the villages of Baden, Rastadt, Kassel, München, Straßburg and others originated in South Russia. As the growing colonies needed more land, daughter colonies—which carried the name of the mother colony with the prefix 'new'—emerged. Later the colonies had to be partially renamed. In 1819, under Alexander I, the German villages got names in memory of Napoleon's victory, such as Tarutino or Borodino.

Map of Grossliebenthal District, Odessa. Source: http://www.rollintl.com/roll/liebenthal.htm The colonies of Großliebental were in close proximity to the city of Odessa. Großliebental (today Welikodolinskoje) was the center of the region densely populated by Germans; it included the colonies of Lustdorf (Tschernomorka), Kleinliebental (Malodolinskoje), Alexanderhilf (Dobroalexandrowka), Franzfeld, Neuburg (Nowogradowka), Mariental (Marjanowka), Josefstal (Jossipowka) and Peterstal (Petrodolina). The colonies maintained close ties to the city of Odessa. As of 1907, a street car line connected the town with Lustdorf, the charming resort town by the Black Sea which attracted many people seeking rest and relaxation. [...] The Kutschurgan coloniesIn 1808, almost 400 families from southern Germany founded colonies on the banks of the Kutschurgan River. The significant colonies were Straßburg (today Kutschurgan), Baden, Selz, Kandel (today Limanskoje), Mannheim (today Kamenka) and Elsaß (present-day Stepnoje). Grain and vegetables, melons, sunflowers, flax, and wine were grown there. Cattle were bred and mills, blacksmith shops and other trade shops were operated. The city of Odessa was vitally important for the economic development of these colonies. The trading of grain and wine was handled at the docks; furthermore, the colonists regularly sold vegetables at the "Priwos" and the "New Bazaar" in Odessa.

Map of Kutschurgan District. Source: http://www.rollintl.com/roll/kutschurgan.htm The Beresan coloniesThe Beresan district was one of the largest districts in the Black Sea region. Today it is located partially in the district of Odessa, partially in the district of Nikolajew. The colonies of Karlsruhe (Stepowoje), Rohrbach (Nowoswetlowka), Worms (Winogradnoje), Rastadt (Poretschje), München (Gradowka) and others belonged to this district. In the Beresan colonies remarkable facilities were located which shed light on the material wealth and cultural prosperity of the German settlers. Among them was a school for the deaf and dumb in Worms. Besides general and parochial schools, an agricultural technical college was located in Landau, the center of the district. In addition, a theater with orchestral accompaniment existed in Landau.

1800's Beresan District. Source: http://www.rollintl.com/roll/beresanmap.htm The Hutterites and Mennonites also settled in southern Russia, mainly in the province of Taurida and in adjoing Cherson and Ekaterinoslav. The HutteritesAlthough the Hutterite faith traces its origins to the 16th century, all Hutterites are descended from a small founding population of less than 24 families (about 150 individuals) who joined the Brethren between the years 1755-1790 in Deutschkreuz (Siebenbuergen), and later in Wallachia (southern Romania) and Ukraine. [2] In 1770, under the threat of continued attacks from Turks, robber bands and Cossacks, the Hutterite Brethren (66 individuals) fled to Russia and established a Bruderhof on a private estate at Vishenka, 200 km northeast of Kiev. It was dismantled in 1802, and in its stead the Radichev colony was established nearby with 44 families. In 1842 the Hutterthal Colony on the Molotschna River was founded. The Hutterites abandoned Radichev and moved to the Taurida province near the Mennonite colony of Molotschna where they would stay until 1874. In 1852 Johannesruh was set up. Due to expansion of the colony 17 families left Hutterthal and establisheded a new colony 4 km north of the site. In 1859, Hutterdorf (Kushcheva) was established. In 1868, the communities of Johannesruh and Hutterthal were dissolved and private ownership was re-adopted. Only the Schmiedeleut maintained community living. They attempted to sell all their belongings and set up a new colony in Scheromet in Tauria. David Hofer and Samuel Kleinsasser moved with their family to Scheromet at this time. In 1868, Neu Hutterthal (Dabritcha) was established. The MennonitesWhen Catherine the Great issued her Manifesto in 1763 inviting farmers from Western countries to settle in Ukraine, the Mennonites of Prussia and Danzig were soon attracted because they were continually encountering restrictions in their economic and religious life. Later the matter of exemption from military service became important. The approximate number that emigrated to Russia in 1787-1870 was 1,907 families, with a total of some 8,000 persons. This constituted a true mass migration of Mennonites in comparison with previous movements. Of this number about 400 families settled at Chortitza, some 1,049 at Molotschna, some 438 at Samara, and 20 families were reported to have gone to Vilna. [3]

Map of the Russian Mennonite colonies in 1875. Source: http://home.ica.net/~walterunger/S-Russia.htm A brief history of the Black Sea Germans since the middle of the 19th centuryThe emergence of Panslavism and a new Russian national identity led increasingly to criticism of the concentration of real estate in the hands of non-Slavic immigrants. In 1887, a law for foreigners was enacted which very much restricted foreigners' rights to lease and acquire property, especially in areas near the borders. As of 1871, the privileges for colonists were abolished and Russian or Ukrainian was made the official language on the German colonies. By the end of the 19th century, lack of land and increasing political pressure had a great effect on the livelihood of Germans. Many of them decided therefore to leave the Black Sea region. As the German Empire was willing to take in only a small number of Black Sea Germans, many settlers participated with Russian and Ukrainian farmers in colonizing Siberia within the framework of the agrarian reform and founded new colonies there. Thousands emigrated to America at the beginning of the 20th century and settled in the states of North and South Dakota and, of course, Canada. At the beginning of the 20th century, the political and economic living conditions of the German settlers by the Black Sea continued to deteriorate. As World War I was approaching, drastic measures were adopted against German settlers. The so-called "liquidation laws" were enacted. They provided for the confiscation of property and the deportation of all citizens with Austrian, Hungarian and German heritage living within a 150 km wide strip of land along the western border. It was carried out only among the Volhynia Germans who lived closest to the western front. The laws were abolished again in 1917. In 1917, a large part of the colonies fell to the newly founded Ukrainian Peoples' Republic. During the War, the Peoples' Republic was occupied by German and Austrian-Hungarian troops. The German colonies were under their protection, and at first this brought in a sense of ease to the situation for the German population. But coercive sanctions by the state to get food and a drastic drop in agricultural production followed the October Revolution. Further dispossession and deportation were the consequences of collectivization and robbed large parts of the rural population of their existence. The ethnicity policies promulgated by the Soviet Union brought about an expansion of cultural freedom for the Black Sea Germans. In the 1920s the Soviet government facilitated the formation of national administrative districts where the particular mother tongues could be used as the official language. As a result, seven German national districts where Germans represented more than 70% of the population, emerged in Ukraine. However, from 1936 on, Stalin's purges led to the dissolution of national councils and districts as well as the deportation of their population. German national districts in UkraineDuring World War II the fate of the Black Sea Germans was determined by the swift occupation of the Black Sea region by Rumanian and German troops. While the Germans living east of the Dnjepr river were deported to Siberia, the Germans living west of the Dnjepr were initially under the protection of the German Reich. They were registered in the so-called "List of German people" which later on served as the basis for handing out German certificates of naturalization. By the end of 1943 the resettlement of Black Sea Germans from the occupied areas to the Warthe-Gau began. Those who survived the travails of the flight were settled on farmsteads of expelled Polish people in order to "Germanize" the region. But the advance of the Red Army soon forced the settlers to continue to fleeing westward. After the war, a large number of the Germans from the Black Sea region who had come to the western occupied zones of Germany managed to go into hiding in order to escape extradition to Soviet occupation forces and repatriation to the Soviet Union. Others were allowed to travel on to America. However, a large number of Black Sea Germans were handed over to Soviet commando units and were deported to Siberian special camps and labor camps, suffering huge losses in the process. Settlement in AlbertaThe Prairies in western Canada, like those in the Dakotas, resembling as they did the steppes of southern Russia, proved very attractive to many German Russians, especially Black Sea Germans. Thousands of them took up the invitation to come to Canada, especially between 1900-1913 when expanding railway branch lines made the Prairies readily accessible to new settlers. Some had originally migrated to the U.S. before continuing on to the Canadian West, in particular to the Dakotas where most Bessarabian, Black Sea and Crimean Germans became wheat growers Following early settlement near Lesterville in 1873, thousands of Germans from the Black Sea areas of Russia poured into Dakota Territory during the following four decades. Their homesteads spread westward and northward until most arable land was homesteaded in what later became South Dakota in 1889. As more and more immigrant Black Sea Germans continued to arrive in Dakota Territory in search of land, their homesteads spread in 1884 into what is now North Dakota. Eventually, their homesteads were located in all arable parts of North Dakota. Lutherans and Roman Catholics were the largest groups among the Black Sea Germans in the Dakotas; other Black Sea Germans settlers included a number of Mennonites and Hutterites, as well as Dobrudja Germans who had briefly lived in southeastern Rumania. By 1920, it was estimated that some 70,000 Germans from Russia lived in North Dakota, most of them originating in the Black Sea region. Many resettled in Alberta and Saskatchewan due to the increasing scarcity of farmland in the Dakotas. Click here for maps of German settlements and Mennonite and Hutterite colonies in Alberta. Notes[1] This section was taken in slightly adapted form from "Germans from the City of Odessa and the Black Sea Region Exhibit." Catalogue text. http://www.lib.ndsu.nodak.edu/grhc/history_culture/history/catalog.html. Accessed on May 21, 2004. [2] Evan Eichler, "Hutterite Genealogy, Founding Families, Churchbook Extractions," http://feefhs.org/hut/hff-2.html. Accessed on May 3, 2004. [3] Canadian Mennonite Online Encyclopedia, "Migrations," http://www.mhsc.ca/encyclopedia/contents/m542me.html. Sources1. "Kleinliebental Homepage," http://www.rootsweb.com/~ukrklieb/english/history/timeline.htm. 2. Glückstal Colonies Research Association," http://www.glueckstal.org/id19.htm. |