The Hutterian BrethrenDefinitionThe Hutterites are the most radical sect of Anabaptists still in existence. They are related to the Mennonites and the Amish, who also practise adult baptism, but the Hutterite doctrine follows strictly a passage from Acts 2:44: "And all that believed were together, and had all things in common." Absolute and eternal authority comes from God, and those that follow Him must give up the transitory nature of worldly living in order to reflect His spiritual permanence. Man's natural rebellious nature is given expression in life outside the community that is afflicted with countless social problems and individual misery, but communal living leads man closer to God. [1] Settlement history in Central and Eastern EuropeThe history of the Hutterites is largely one of persecution. In 1528, Moravian (today located in the Czech Republic) and Tyrolese peasants organized under Jakob Hut[t]er in order to oppose war and war taxes. But their collective way of living and religious non-conformity (adult baptism, separation of church and state, and unwillingness to bear arms) angered the authorities, and in 1536 Huter was arrested and burned at the stake, as had been several of the early founders of the movement. Many Hutterites found refuge with Moravian nobles throughout the 16th century, and by 1600 there were over 15,000 members in Moravia. Yet, all Hutterites in Russia were descended from a small founding population of less than 24 families (about 150 individuals) which joined the Brethren between the years 1755-1790 in Deutschkreuz (Siebenbuergen) and later in Wallachia (southern Romania) and Ukraine. [2] The religious wars of the 17th century forced the Hutterites to flee from Moravia to Slovakia, then on to Hungary, and to Transylvania (in Rumania) and Wallachia (also in Rumania). In 1770, under the threat of continued attacks from Turks, robber bands and Cossacks, the Hutterite brethren (66 individuals) fled to Russia and established a Bruderhof on a private estate at Vishenka, 200 km northeast of Kiev. It was dismantled in 1802, and in its stead the Radichev colony was established nearby with 44 families. When Empress Maria Theresa displaced all non-Catholics to the fringes of her domains in 1755, Lutherans from Carinthia (Austria), named Waldner, Wipf, Hofer, Stahl, Kleinsasser, Wurtz—still common names among the Hutterites today—came into contact with the Hutterites and helped the movement. In Russia, peace and prosperity existed for many years, but the Brethren also experienced difficulties in maintaining their isolated, communal life style. In 1842 the Hutterthal Colony on the Molotschna River was founded. The Hutterites abandoned Radichev and moved to the Taurida province near the Mennonite colony of Molotschna where they would stay until 1874. In 1852 Johannesruh was set up. Due to expansion of the colony 17 families left Hutterthal and establisheded a new colony four kilometers north of the site. In 1859, Hutterdorf (Kushcheva) was founded. In 1868, the communities of Johannesruh and Hutterthal were dissolved and private ownership was re-adopted. Only the Schmiedeleut maintained community living. They attempted to sell all their belongings and set up a new colony in Scheromet in Tauria. David Hofer and Samuel Kleinsasser moved with their family to Scheromet at this time. In 1868, Neu Hutterthal (Dabritcha) was established. Emigration from Eastern EuropeThe Hutterites in the U.S.The Russification policies of the Tsarist government in the second half of the 19th century pressured the Hutterite colonies into assimilation. In April 1873, Paul Tschetter and his uncle Lorenz Tschetter were sent as emissaries for the Hutterites to search for new potential settlements in North America. They returned to the colonies in in July 1873. Tschetter suggested that the Hutterites settle in America. In May 1874, the Schmiedeleut under Michel Waldner of Scheromet immigrated to Bon Homme County in South Dakota where they flourished. The Dariusleut and Lehrerleut followed shortly thereafter. [3] However, with the outbreak of the First World War, the Hutterites were again compelled to search for another country that would have them. In the U.S., they experienced strong discrimination because—although they could hardly be called "German" after 400 years of travails in Switzerland and Central and Eastern Europe—they were identified with the Kaiser's "Teutons" by a sometimes fanatical local patriotism. Young Hutterites decided to register and be examined by military physicians, but they refused the uniform and service in the war. As a consequence, many were beaten, and several were killed. The Hutterites in AlbertaThe Hutterite colonies in the U.S. suffered greatly during the First World War. Their livestock was seized and the money was used for the war effort; they were not allowed to use the German language or their dialect in school or worship. However, Canada wanted the Hutterites to help develop the agricultural potential of the Prairies. The authorities gave the Hutterites assurances that they would not be forced to do military service, and they were also assured religious freedom.

From early summer 1918 on, there were occasional reports of "Germans" entering Alberta from the U.S. and buying up huge tracts of fertile farmland in the south. These "Germans," the Hutterites, were met with great hostility because of their anti-war convictions, their land purchases, and their clannishness and refusal to integrate in Canadian society. After the establishment of six colonies in Manitoba and four colonies in Alberta, the government, under pressure from the local population, withdrew its promise and stopped further immigration of Hutterites. After the end of the War, the hostilities decreased and four more colonies were established in Manitoba and eleven in Alberta. But the rapid expansion of the Hutterites and the additional Mennonite settlements continued to alarm the local population, and strong protests arose against their purchases of the best land. By 1940, there were 52 colonies in Canada. The beginning of the Second World War again brought an end to any goodwill towards the Hutterites. This time, the right to refuse military service was granted by the Canadian government, and Hutterites did substitute service in public institutions, hospitals, national parks, paper mills, etc. and supported the hospital field services financially. The Hutterites represented stiff competition in agriculture, and again the government ceded to demands of the local population, who blamed them for the decline of the family farm and of small towns in rural Alberta, and resented their perceived unwillingness to fight against the Nazis. In 1942, Alberta's Social Credit government dealt with the long-simmering "Hutterite problem" and put restrictions on their land purchases in the Land Sales Prohibition Act that forbade the sale of land to enemy aliens, Hutterites and Doukhobours. In 1947 the Act was amended to exclude only enemy aliens. Hutterites were permitted to buy up to 6,400 acres if the site was not closer than 60 km from an existing colony. In 1960, the Act was amended, but complaints against further expansion continued. The Hutterites were criticized for

Small towns and villages feared the collapse of the public schools if non-Hutterite families moved away. In the mid to late 1950s there was again public concern over the "excessive" expansion of Hutterite colonies, and revisions of the Land Sales Prohibition Act and the Communal Property Act were made. In the sixties, the hostility against the Hutterites continued unabated in the rural areas. A charge against a Hutterite colony for alleged infringement of the Communal Property Act started a series of court proceedings aimed at the abolition of the Act because it was considered to be discriminatory and ultra vires. This event marked the beginning of a change in public perceptions about the Hutterites. Subsequently the Hutterites received wider public acceptance with "equal rights for all" especially from the urban population, but rural opposition to the Hutterites continued. Taxation proved to be a vexing issue. The Dariusleut Hutterites, who had refused to pay income tax for religious reasons, began a series of court proceedings that wound its way through the courts for years all the way to the Supreme Court and resulted in a different system of taxation for them. However, "while successful initially in challenging deemed individual taxtation of overall colony profits, the victory was actually hollow, as the colonies were then taxed at a corporate rate, rather than being tax exempt as religious charities. The corporate rate, given that colonies paid no wages to members of the colony so as to be able to deduct these amounts form profits, turned out to be much higher than the scheme that the Hutterites had challenged. A second seeries of court cases was then launched by the Dariusleut, again unsuccessfully, and finally litigation was dropped in favor of a negotiated agreement with the government as to taxation on a deemed individual basis." [4] In 1972, the new Progressive Conservative government passed a Bill of Rights, and repealed the Communal Property Act in 1973 against strong protests from members of the legislature in southern Alberta. An advisory committee on the expansion of colonies consisting of representatives from the Government and the Hutterites was set up, but it could only make suggestions not to locate a new colony within 15 miles of an existing colony. The Hutterites have fought the Federal government in several tax cases, but since the 1970s, relationships between the Hutterites and the local population have improved considerably, and the Alberta government has strongly supported their rights as a religious community. But there has been some residual resentment and resistance against them. In the late 1980s and the 1990s, sporadic opposition would again be raised against the Hutterites, this time mostly on ecological grounds, as the Hutterites' neighbors objected to the huge agricultural industries proposed by the colonies. In 2000, the MLA from Little Bow in southern Alberta introduced—unsuccessfully—a private bill which would make it illegal for anyone to own in excess of 15 per cent of the total amount of arable farmland in any municipal district or county. At that time, a spokesman for the Hutterites defended their colonies saying that they were family farms just like everyone else's; the colonies just happened to have more families living on them. Each colony is, after all, a separate legal identity. It was pointed out that in Warner County—the county with the largest Hutterite holdings—59,792 hectares or 13.5% was owned by the Hutterites in 2000, but the Mormon Church owned the 41,600 hectare Desert Ranch, by far the largest Alberta farm corporation, and no complaints were made about this fact. In 2003, the same MLA introduced a private member's bill to raise the dropout age for Alberta's school children from 16 to 17. He maintained that Hutterite children were being short-changed in their education, and this could even be dangerous for them in the workplace. Critics maintained that this was another thinly-veiled attack on the Hutterites' exercise of their religious freedom because they take their children out at 15. It was nonsense to say that Hutterites cannot understand pesticide labels because their children quit school at 15 or after Grade 9, said the spiritual leader of one of the Hutterite colonies. At any rate, they would not comply with the provisions of such an act. The bill passed, but was not proclaimed. In 2006 another potential conflict arose: A southern Alberta Hutterite community - the Wilson Colony, located east of Lethbridge near Coaldale -- that believes the Bible forbids being photographed won a court challenge against mandatory pictures on driver's licenses. Some Hutterites believe the Second Commandment prohibits them from willingly having their picture taken. A Court of Queen's Bench Justice ruled that a provincial law requiring digital photos on driver's licenses violated the religious freedom of the conservative religious sect. In 2003, Alberta had started requiring that all new licenses include a photograph as a matter of security. Members of the Wilson colony refused to have photos taken in deference to their religion. As a result, the number of licensed drivers in the community dwindled from 37 to 15, as old licenses expired, threatening the survival of its farming operations.

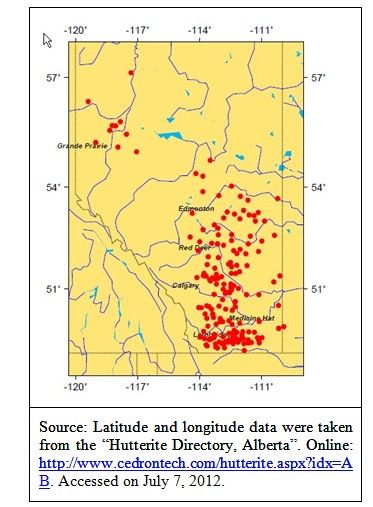

This case would occupy these Hutterites and the courts until 2010. First, the Province appealed the decision to the Alberta Court of Appeals and finally to the Supreme Court which upheld the provincial law for photo licenses. Chief Justice McLachlin found that the government's need to fight fraud was pressing, and that driving was not a right, so the government was entitled to attach legitimate conditions to it. Then the Wilson Colony and the Three Hills Colony, after musing about leaving Alberta because of the ruling, asked the Supreme Court for a rehearing, but the court refused to grant it. The Alberta government was said to be willing, however, to work with the Hutterites to find a "sensitive" solution. One option might be that licenses be carried in special pouches that would hide the photos from the Hutterites, but make them available if requested by authorities. Several suggestions -- including fingerprint identification, special pouches to hide the photos, and specialized pin numbers -- were floated as ways around the requirements, but the province did not budge from its photo requirement although they were still reported to be open to hearing ideas from the colony leaders on how to accommodate them. None of the ideas they brought forward meet the requirements for an Alberta driver's license. On March 3, 2010 the Edmonton Journal ran an editorial urging the Hutterites to obey the law and have photos taken for their driver's licenses. The paper said that there are logically two further choices -- to not drive, or to relocate to a jurisdiction in which a photo licence isn't needed. If the Hutterites reject those admittedly unattractive options and choose to drive illegally, that will have been their call, and not one forced on them by a disrespectful community, the paper said. Albertans respect diversity and religious convictions as much as any people, but the law must be enforced. Although provincial governments in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario made exceptions to driver photo laws for their Hutterite populations the Minister responsible for licensing drivers said the Alberta law treated everyone equally. Subsequently there was no further mention of this case in the media or the legal literature. Separate population statistics for Hutterites have only been kept since 1971. According to the censuses, there were 6,100 Hutterites in Alberta in that year, 7,395 in 1981, 9,980 in 1991, and ten years later 12,330 Hutterites resided in the province. Of the latter, the great majority lived in the south of the province: in the Lethbridge area (N=ca. 4,400), the Medicine Hat area (N=1,680), the Calgary area (N=2,000), east of Drumheller (N=400), in the Red Deer region (N=2,200), north and east of Edmonton (N=1,100), and in the Grande Prairie area (N=400). Of the total of 166 Hutterite colonies reported in 2003 97 belonged to the Dariusleut and 69 to the Lehrerleut. It was noted above that 20 colonies were founded between 1996 and 2000: two in the Medicine Hat area, eight around Lethbridge, four in the Drumheller area, three near Red Deer, two east of Edmonton, and one north of Grande Prairie. In 2003, there were 166 colonies in Alberta, 97 belonging to the Dariusleut and 69 to the Lehrerleut. The great majority lives in the south of the province, ca. 4,400 in the Lethbridge area, 1,680 in the Medicine Hat area, but there are Hutterites as well in the Calgary area (ca 2,000), east of Drumheller (ca. 400), in the Red Deer region (ca. 2,200), north and east of Edmonton (N=1,100), and in the Grande Prairie area (N=400).

According to one private source, in 2006 there were 176 colonies in Alberta: 105 belonged to the Dariusleut, 69 to the Lehrerleut, one to the Schmiedeleut, and one was reported "unspecified." However, the 2011 Census reported only 165 colonies with 15,600 members. The website www.hutterites.org (accessed on September 15, 2013) reported 168 colonies (98 Dariusleut colonies across the entire province but concentrated in north-central Alberta; and 69 Lehrerleut colonies, almost exclusively in southern and south-central Alberta). There has been some immigration of Hutterites to Alberta. According to the 2001 Census, of the 12,330 Hutterites in the province, 200 were immigrants. 95 had entered Alberta before 1961; subsequently, about 20 Hutterites have immigrated every decade. Nowadays, the Hutterites have colonies in Canada, the U.S., Japan, Paraguay and Uruguay, and—once more—in Germany. There are three different groups of Hutterites living in North America, the Schmiedeleut, the Dariusleut and the Lehrerleut, numbering altogether 36,000 on ca. 430 colonies. Life on the coloniesOrganizationIn every Hutterite colony (Bruderhof), the minister or spiritual leader is also the "chief executive" and he, along with an advisory board, makes the day-to-day decisions. The minister's duties include conducting church sermons, marriages, baptisms, funerals, and disciplining members of the church. The advisory board consists of the colony manager, the farm manager, and two or three witness brothers who are elected for life. All members of the colony are provided for and nothing is kept for personal gain. Hutterites do not have personal bank accounts; rather, all earnings are held communally and funding for necessities is distributed according to one's needs. EducationObtaining a proper education is a very important goal in many colonies. Children from two and a half to five years start their education in kindergarten. There they learn how to sing Hutterian songs, to pray, to play, to share, and to eat properly. After the age of five, they attend regular English and German classes. In addition, they graduate to the children's dining room (Essensschule) where table manners, thankfulness, respect, and obedience are strongly encouraged. Hutterite children are initiated into adulthood when they are 15 years old. They start eating with the adults and are considered adults.

Hutterite schools follow the approved Alberta curriculum during the regular school day. Normally, the colony supplies the building, heating, and the maintenance costs. The local public school board selects and pays the salary of the teachers, administers the school, and in most cases, pays a small rent for the building. The children are taught the basics like math, language arts, social studies, science, and German. Usually there are other optional courses such as music, biology, or carpentry. On the less conservative colonies in Manitoba, older children are taught by distance education, and some schools use teleconferencing. They may also take courses in computer literacy. Due to increased sophistication in livestock production, farming, and manufacturing, Hutterites have realized that a solid education is a necessity. Many colonies in Manitoba are finding it necessary for students to complete at least a Grade 12 education, and some of them are even sending a few of their members to the university to obtain a teaching degree. There is a program at Brandon University in Manitoba where Hutterites are being trained to become teachers on their own colonies. It is felt that a colony's own teachers will offset the worldly influence of the outside teacher.

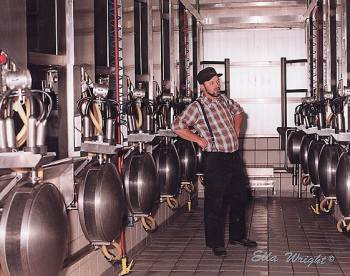

There are also vocational training courses. In addition to formal education, Hutterites emphasize work education. Young people are assigned different jobs on the colonies for months at a time to learn a trade. For example, a young man would work with the farm manager for the summer months, and spend the winter months with the carpenter on a building project or in a hog-raising facility. The children receive two hours of German instruction daily from their own German teacher. Many teachers have replaced the Tyrolean dialect with the use of standard German as the language of instruction. In Alberta, university-outreach programs as described above for Manitoba do not exist, but the German language consultant at Alberta Learning assists the German teacher. WorkEach Hutterite colony has to provide for between 60 and 160 persons. Most are crop producers and farms and raise a large amount of life stock. In addition, manufacturing is gaining momentum on many colonies.

Every member of the Bruderhof is willing to do any work as a service for the whole body. The brotherly atmosphere within and between the different work departments is more important than economic considerations. There is no differentiation in value between income-producing work, such as farming and colony industries, and the many services needed for the daily life of the community. Every person on a colony is assigned a job. Some assignments may be carpenter, chicken man, farm boss, etc. Each person is in charge of a team with usually one or two helpers. The Hutterites have always tried to obtain maximum return on their investment—the money to be used for the establishment of more colonies—by rationalization and mechanization. They were among the first to use computers to manage cattle identification and feeding patterns, and they quickly set up wind-powered turbines where this was economically possible. They have also ventured into large-scale operations, and have been very successful in doing so. In 1973, the 7,200 Hutterites in Alberta owned 580,000 acres—1.2% of the total arable land areathen. By 1997, Alberta's 151 colonies owned 1.5 million acres of land (1% of the total farmland), but produced one third of the dairy products, eggs, and hogs in Alberta and had a virtual monopoly on down feathers. 10% of the country's milk supply came from Hutterite farms. Recently, attempts to increase intensive farming (e.g., by setting up huge farms with 5,000 to 6,000 pigs or 15,000 chickens) have led to resistance from surrounding communities who opposed the inevitable environmental pollution by these "factory farms."[5] Hutterite men and women in their black clothes are familiar sight at farmer's markets across the province where they sell their produce for a good price. Leisure timeHutterites do different things in their leisure time. Boys and men play sports, such as hockey, volleyball, baseball, soccer, football, and lacrosse. Females are more involved in crafts, such as creating flower arrangements, knitting, crocheting, needle-point and rug-making. Both males and females spend a lot of time singing. A favorite pastime is visiting other colonies. Young people from different colonies get to know each other by visiting for the day or the weekend for social purposes or for helping others pick vegetables or erect buildings. Hutterites attend a half-hour church service almost every day besides a 1 to 1.5 hour service every Sunday and common religious holidays. German language maintenance

Among Albertan Hutterites, the age distribution in 1991 was the following: 4,035 Hutterites were less than 15 years of age (=33%); 1,765 were between 15 and 24; 2,585 Hutterites ranged between 25 and 44 years; 1,170 were between 45 and 64, and 415 Hutterites were 65 years of age or older,—a distribution very much younger than in the rest of the Albertan population. In 2001, 37% of the Hutterites were children ranging in age from 0 to 14, another 19% were between 15 and 24 years of age. The fact that Hutterite families have many children has important implications for the maintenance of German in the province. Of the 27,550 Albertans who used German as their home language in 2001, almost half (N=12,330) were Hutterites. By contrast, more than 150,000 Albertans claimed to have German origin and another 423,000 gave German as one of their origins, and 78,000 had German as their mother tongue. Among non-Hutterite Albertans who spoke German at home, more than 60% were 45 years of age or older. Clearly, German as a home language is dying out among the post-WW II immigrants, but thriving among the Hutterites. IssuesIt would seem to be difficult for Hutterite families to keep their children from leaving the colony; after all, colony life is highly structured and disciplined, leaving little freedom for the individual. Also, the children are more familiar than ever with the outside world and its lures. Yet, only very few Hutterites do leave the colony every year, and when they do they are on their own; in most cases, the colony breaks off all relations with those who haven chosen life "on the outside." Those who have left find it difficult, at least initially, to start their new life. Critics maintain that the Bruderhof indoctrinates its member with the benefits of communal living and that children are deliberately kept at a minimum level of education. Over the years, "well-meaning" critics have charged that by compelling the Hutterite colonies to offer high-quality publication the "Hutterite problem" would be solved because well-educated children would want to escape the authoritarian environment in which they live. The recent attempt to raise the drop-out age may also be considered an attempt to "liberate" the children from the shackles of Hutterite ideology. Yet, when asked Hutterites—even those who have left the colony—have high praise for the supportive communal atmosphere and the loving care with which the Bruderhof looks after the needs of individuals. Critics will, of course, claim that indoctrination has been successful. Notes[1] "Hutterite settlement," http://collections.ic.gc.ca/pasttopresent/opportunity/hutterite_settlers.html. Accessed on February 13, 2004. [2] Evan Eichler, "Hutterite Genealogy, Founding Families, Churchbook Extractions," http://feefhs.org/hut/hff-2.html. Accessed on May 3, 2004. [3] Evan Eichler, "A Brief History of the Hutterian Brethren (1755-1879)," http://feefhs.org/hut/hut-hist.html. Accessed on May 3, 2004. [4] Alvin J. Esau, The Courts and the Colonies: The Litigation of Hutterite Church Disputes (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004, p. 51). [5] Assessing an Alternative Solution to Labour Shortages in the Food and Beverage Processing Industry in the Prairie Provinces. SourcesThis section is based, in large part, on 1. "The Hutterian Brethren. Hutterites living in Community in North America," http://www.hutterites.org/. Sections on history, religion, structure, education, teachers, livelihood, leisure time, and organizational structure. 2. The Canadian Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, "Hutterian Brethren." http://www.mhsc.ca/encyclopedia/contents/ H8888ME.html. Accessed on February 13, 2004. 3. Berger-Prössdorf, "Hutterites: An Historical Overview," http://mtprof.msun.edu/Spr1993/TBP.html. Accessed on February 13, 2004. 4. Manfred Prokop and Gerhard Bassler, German language maintenance across Canada (Edmonton: 2004). |