Dispersed Minorities and

Segmental Autonomy:

French-Language School Boards in Canada

EDMUND A. AUNGER

___________________________________________________________________________________________

An ethnic minority is

more likely to gain political autonomy if it is geographically concentrated;

such autonomy is rare when the minority is territorially dispersed. This article examines Canada's recent

experience in granting segmental autonomy to its dispersed French-speaking

minority. After more than a century of

majority rule in the field of education, most Canadian provinces have only now

established French-language school boards responsible for administering

minority schools. The adoption of this

new policy was unexpected; its implementation was achieved with great

difficulty. The province of Alberta,

where French-language school boards were established in 1994, serves as an

instructive case study of the implementation, the organization and the

structure of segmental autonomy in education.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

The

difficulty in governing a society characterized by separate and self-contained

ethnic groups has been widely acknowledged.

Gabriel Almond, in his classic typology of comparative political

systems, asserted that all fragmented societies were likely to be unstable.[1] A fragmented society was defined by its

multiple political cultures, rather than by multiple ethnic groups;

nevertheless, the proposition has been frequently generalized to encompass any

plural society regardless of the dividing cleavage. Ethnic divisions have proved to be a particularly durable

cleavage, refusing to dissipate with political development and with functional

modernization as Rokkan once predicted so convincingly.[2]

While

recognizing the dangers posed by deep social divisions and conflicting ethnic

loyalties, Lijphart has proposed a model of political governance that holds out

the promise of democratic stability.[3] In Lijphart's

view, majoritarian and adversarial governments stimulate violence and

disintegration in plural societies, while coalescent and consociational

governments contribute to both democracy and unity. The defining characteristics of consociational government are

grand coalition, mutual veto, proportionality and segmental autonomy.

Segmental

autonomy means minority rule, not in all domains, but in the area of the

minority's exclusive concern. While

matters of mutual concern are to be resolved by joint agreement reached through

the mechanisms of coalition, veto and proportionality, matters of particular

concern are to be resolved by delegating authority to the individual

segments. In this way, segmental

autonomy removes sensitive and potentially destabilizing issues from the larger

political arena. It reduces the

likelihood that such issues will be subject to inter-ethnic competition. Further, although this is often left unsaid,

such autonomy is likely to provide a just guarantee of minority rights. Important minority concerns will not be left

to the discretion of an unsympathetic majority.

The

separation and isolation of the various segmental groups have been deemed an

important condition of consociational government.[4] Clear

boundaries have the advantage of limiting contact between such groups and

thereby reduce the possibilities for conflict.

Leaders become the chief bridge between the segments and the possibility

of elite cooperation is enhanced. These

boundaries are maintained by separate political and social institutions or by

territorial segregation.

Territorial

segregation, in particular, facilitates segmental autonomy. In Belgium, for example, the geographic

separation of the official language communities has contributed significantly

to the recent creation of a federal state, where each community has

responsibility for educational, cultural, linguistic and personalizable matters

within its language region.[5] In Northern

Ireland, on the other hand, the territorial mixing of the two religious groups

has undermined consociational strategies, and particularly efforts to increase

minority autonomy. Catholics very

seldom constitute regional majorities and they have had great difficulty

gaining political control in local affairs.[6]

Education

is almost inevitably an issue of particular concern to ethnic minorities, not

the least because of its intrinsic links to such crucial areas as language,

culture and religion. A 1982 amendment

to the Canadian constitution, and subsequent jurisprudence, has guaranteed

official language minorities substantial control over their schools. This guarantee has had particularly

significant consequences for Canada's dispersed French-speaking minority.

This

article will examine the evolution of the minority education question and the

recent establishment of French-language school boards, with particular emphasis

on those Canadian provinces, notably Alberta, where French-speakers constitute

a dispersed minority. It is suggested

that these school boards provide an instructive example of segmental autonomy.

Dispersed Minorities

Taken as a whole, Canada's French-speaking

minority is not dispersed but concentrated: 87.5 per cent live in census

divisions where they are a majority (see Table 1). This situation may be attributed to the fact that 84.5 per cent

of Canada's French-speakers live in one province--the province of Quebec--where

they constitute a substantial, and ever-increasing, majority of the

population. According to the most

recent census, in 1991, French-speakers make up 83.3 per cent of Quebec's

population; and virtually all (99.9 per cent) of Quebec's French-speakers live

in census divisions where they are a majority.

In 1837, French-speakers made up 72 per cent of Quebec's population; in

1871, 78 per cent and, in 1931, 79 per cent.[7]

In

the other nine Canadian provinces, however, French-speakers are a relatively

small minority and their proportions have steadily declined. While in 1951 French-speakers made up 7.3

per cent of the population of Canada, excluding Quebec, by 1986 they numbered

only 5.0 per cent of this population.[8] The decline

was particularly marked in the most English-speaking regions of the country

where the proportion of French-speakers decreased during the same period from

3.4 per cent to 2.4 per cent.

In

each of these nine provinces, except New Brunswick, the minority is also

territorially dispersed. This

dispersion may be measured by calculating the level of minoritization in

Canada's 290 census divisions (see Table 1).

It should be noted, however, that this measure is influenced by the size

of the census divisions. In New

Brunswick, for example, where there are 15 divisions, the resulting

calculations show that 63.4 per cent of the French-speakers live in areas where

they constitute a majority. However, a

somewhat different measure, based on the smallest unit available, the

province's 277 census subdivisions, has previously shown that 74.3 per cent of

the French population live in areas where they are a majority.[9] If smaller

census units were used for other provinces, our measurements would similarly

show a somewhat greater concentration of the minority population.

TABLE 1

DISTRIBUTION OF FRENCH-SPEAKERS IN CANADIAN PROVINCES,

BY CENSUS DIVISIONS, 1991

|

Province |

French-speaking |

Distribution by

Proportion |

|||

|

|

Population |

In Census Division |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N |

% |

10%+ |

50%+ |

90% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

British Columbia |

58,685 |

1.8 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Alberta |

64,655 |

2.5 |

8.4 |

- |

- |

|

Saskatchewan |

24,300 |

2.5 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Manitoba |

55,300 |

5.1 |

19.9 |

- |

- |

|

Ontario |

547,300 |

5.4 |

62.1 |

8.8 |

- |

|

Quebec |

5,746,625 |

83.3 |

100.0 |

99.9 |

62.1 |

|

New Brunswick |

250,175 |

34.6 |

92.9 |

63.4 |

14.0 |

|

Prince Edward Is |

6,285 |

4.8 |

73.3 |

- |

- |

|

Nova Scotia |

39,425 |

4.4 |

54.5 |

- |

- |

|

Newfoundland |

3,235 |

0.6 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Canada |

6,798,575 |

24.9 |

93.6 |

87.5 |

53.0 |

Note. The French-speaking population is defined to include all those who

claimed French as their mother tongue.

It includes, for example, those who claimed French as their sole mother

tongue (95.7%) and those who claimed it as only one of two or more mother

tongues (4.3%). The latter situation is

most common in those regions, such as western Canada, where French-speakers are

a dispersed minority.

There are a total of 290 census

divisions in Canada, including 30 in British Columbia, 19 in Alberta, 18 in

Saskatchewan, 23 in Manitoba, 49 in Ontario, 99 in Quebec, 15 in New Brunswick,

3 in Prince Edward Island, 18 in Nova Scotia, 10 in Newfoundland, 5 in the

Northwest Territories and 1 in the Yukon Territory.

Source. Calculated from: Canada,

Statistics Canada, Profile of Census Divisions and Subdivisions, 13 vols

(Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services, 1992).

For some purposes, the

absolute number of French-speakers in a region is more relevant than the

proportional number. The granting of

regional autonomy, particularly in educational services, for example, often

depends on the existence of a sufficient number of clients. Canadian legislation frequently limits the

provision of minority services to areas ‘where numbers warrant.’ Figure 1 shows

the regional dispersion of French-speakers (and English-speakers in Quebec) based

on the absolute number in each census subdivision. It confirms our earlier observation that French-speakers are

generally dispersed throughout the country, although there are important

regional variations. In New Brunswick,

the French-speaking minority is relatively concentrated; in Alberta and

Saskatchewan, however, it is much more widely scattered.

FIGURE 1

MAP OF OFFICIAL LANGUAGE MINORITIES IN CANADA:

POPULATION DISTRIBUTION, BY CENSUS SUBDIVISION, 1986

Note. This map shows the distribution

of English-speakers in Quebec, and French-speakers outside Quebec. Each dot is equal to 100 persons.

Source. Adapted from: Canada, Department of the Secretary of State, Annual

Report by the Secretary of State on his mandate with respect to official languages,

1988-1989 (Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services, 1989), p. 86.

If each of Canada's ten

provinces are treated as individual cases, and a measure of minoritization is

used to evaluate dispersion, then it may be concluded that French-speakers are

generally a dispersed minority. Quebec

and New Brunswick are the only exceptions to this conclusion. In both these provinces French-speakers

constitute local majorities. Indeed, as

noted earlier, Quebec's French-speakers are also a provincial majority and, for

this reason, the Quebec case will not be examined here. On the other hand, the New Brunswick case

will be retained for reasons of comparison; it provides an example of a

regionally-concentrated minority.

Majority Rule

Education is a provincial responsibility under

the Canadian constitution and, until 1982, no guarantees existed for

French-language schooling. Section 93

of the Constitution Act, 1867 protected denominational schools, both

Protestant and Catholic, in provinces where these schools already enjoyed legal

rights at the time of union. Insofar as

French-speakers were also Catholics, they thereby benefited from partial

protection, at least in some parts of the country. This protection was not needed in Quebec, of course, where they

enjoyed majority status. Since the

federal system recognized provincial autonomy in education, French-speaking

Quebecers were ultimately assured that they would control their own school

systems.

Elsewhere,

in the decades following Confederation, French-speakers were a minority and

subject to the dictates of an English-speaking Protestant majority. This majority lashed out against both

French-language and Catholic schools wherever these were perceived as

sufficiently important to warrant attention: English was imposed as the only

language of instruction. Majority rule

thus worked against the French-language minority. Minority rights were often suppressed. Stormy conflicts were the usual result.

In

New Brunswick, the provincial government adopted the Common Schools Act in

1871 and thereby imposed universal, non-denominational and, in effect,

English-language education, financed from public funds. Denominational schools were excluded from

such funding and Catholics withheld their school taxes in protest. The government took a hard line against this

opposition, confiscating private property to meet unpaid taxes. This policy garnered majority support and in

1874 the government was re-elected on the platform of `Vote for the Queen

against the Pope.' The resulting

polarization, however, lead to an outbreak of rioting in the French-speaking

village of Caraquet, following a contested school meeting.[10] Two people

were killed.

The

riots shocked the province and the Protestant government immediately initiated

negotiations with the Catholic opposition, derisively referred to as the

`French Brigade.' The negotiations were

secret and the resulting compromise was concealed from the public for some

eighteen years. The most significant

long-term consequence of the riots was a complete reversal in political

behaviour, from majority rule to overarching cooperation. Subsequent cabinets

were coalitions between English and French, Protestants and Catholics, Liberals

and Conservatives.[11] Various

cooperative strategies were introduced, including depolitization,

proportionality and compromise.

A

particularly important element in the new compromise was the authorization to

communicate and study in the French language in elementary schools.[12] English,

however, remained the primary language of instruction. The success of this agreement was due, in no

small part, to the regional isolation of the French-speaking community of the

time. Religious and language

concessions could be implemented with little effect on the English-speaking

Protestant majority and, often, without its knowledge. Further, because of their territorial

concentration, the French could easily exercise some local control in school

and municipal affairs. In 1967, when

the educational system was completely overhauled as part of the Equal

Opportunity Programme, there were some 422 school districts in the province,

each with financial and administrative autonomy.

In

western Canada, the demographic balance that had existed between the English-

and the French-speaking populations at the time of Confederation was upset by a

wave of immigration from Ontario during the 1880s. By 1901, French-speakers constituted only six per cent of the

population of the future province of Alberta and seven per cent of the

population of Manitoba. In both cases,

majority rule meant an end to minority rights.

In

Manitoba, the legislative assembly passed an Official Language Act in

1890 imposing English as the only language of the assembly and the courts,

thereby cancelling the official status of French. The same year, the legislature voted a Public Schools Act

that established a system of non-denominational schools under the direction of

a provincial advisory board.

Denominational schools were not entitled to public funding while, within

the public system, instruction in French and the teaching of religion were

prohibited by the advisory board.[13] The

establishment of a non-denominational English-language system met with vigorous

protests from the French-speaking Catholic minority. A temporary compromise was negotiated between the federal and

provincial governments in 1896 permitting religious instruction and the use of

French where numbers warranted. These

provisions were repealed in 1916, however.

In

the Northwest Territories, the legislative assembly similarly adopted a

resolution in 1892 declaring English to be the sole language of its proceedings

and records. The same year, the School

Ordinance was amended to establish English as the only language of

instruction.[14] A subsequent

modification allowed for the teaching of a primary course in the French

language, if this instruction was limited to one hour per day and if the

parents were willing to pay a special rate.

These provisions were carried over into the newly-created provinces of

Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905.

English continued to be the only language of instruction permitted in

the schools of these provinces, with minor exceptions, until 1968.

In

Ontario, the province with the largest French-speaking minority, the School

Act originally made no provision for the language of instruction. French-language instruction was tolerated in

publicly-funded schools until at least 1889.

This tolerance was apparently based on the assumption that the

assimilation of Ontario's French-speakers was inevitable in such an

English-speaking province, and that it could best be achieved voluntarily,

without coercive measures.[15] Nevertheless,

when the French-speaking population showed no sign of waning, sterner measures

were deemed necessary. In 1885 new

regulations imposed the use of English (for a minimum of two hours in the lower

grades and four hours in the upper grades) and also required that every

teaching candidate pass examinations in English grammar. In 1889 further regulations removed all

French-language textbooks from the list of authorized books. A more draconian measure was adopted in 1912

when Regulation 17 prohibited the use of French as a language of instruction. This regulation was actively resisted, and

even defied, by many Franco-Ontarians; indeed, some French-language elementary

schools continued to operate within the separate school system. The regulation was repealed in 1927.

Historically,

then, majority rule has not worked to the advantage of Canada's dispersed

French-speaking minority. Wherever

French-speakers were found in significant numbers, the provincial governments

intervened to prohibit the use of French as a language of instruction. New Brunswick is the major exception to this

trend. However, in that province, the

French-speaking population was territorially concentrated and the government

adopted a consociational strategy.

Segmental Autonomy

In this context, the introduction of segmental

autonomy in French-language education appears as an unexpected and unusual

development. Except in New Brunswick,

this autonomy may be traced in large measure to the adoption of the Canadian

Charter of Rights and Freedoms as a part of the Constitution Act, 1982. This charter provided for minority-language

educational rights; it was not immediately apparent that these rights also

included the management and control of minority schools.

The

modern roots of the movement to establish French-language schooling may be

found in the report of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism.[16] This

commission of inquiry was appointed in 1963 in response to growing political

unrest in Quebec: an ever-increasing number of French-speakers demanded greater

protection for their language and greater autonomy for their province. André Laurendeau, editor-in-chief of the

influential Montreal daily newspaper Le Devoir, was the first to express

the need for such a commission, and he was subsequently appointed its

co-chairman.

In

its 1968 volume on education, the commission recommended that the

official-language minority be guaranteed its owns schools in districts where it

constituted ten per cent or more of the population and in urban centres where

the number of eligible students made it practicable.[17]

Significantly, however, no recommendation was made for autonomous

minority-language school boards. On the

contrary, where there were French and English schools in a district, these

would be under the jurisdiction of the same school board. It was, however, suggested that this board

include representatives of each language group.

Although

the recommendations of the federal commission were in no way binding, they were

to have considerable influence on public opinion and government policy. Pierre Trudeau, prime minister of Canada

between 1968 and 1984, was eager to expand French-language services throughout

Canada, rather than to devolve greater political autonomy to Quebec. By strengthening the French-speaking

presence outside Quebec, Trudeau hoped to successfully combat separatist sentiments

within Quebec: French-speaking

nationalists might thereby be induced to identify with Canada, rather than with

Quebec. The Canadian government, rather

than the Quebec government, could then claim to be most appropriate spokesman

for the country's French-speakers.[18] Thus, the

political dissatisfaction expressed by Quebecers provided the impetus for

increased services to French-speakers living outside Quebec. In 1968, Trudeau's government adopted its

first Official Languages Act, granting official status to both English

and French and promising bilingual services in districts throughout Canada

where there was sufficient demand.

New

Brunswick was the first province to respond in a substantial way to the

commission's recommendations when it adopted its own Official Languages Act

in 1969. Section 12 of this act, as

proclaimed in 1976, required that instruction in the province's schools be in

the mother tongue of the pupil: English instruction for English pupils and

French instruction for French pupils.

In 1981, however, New Brunswick went even further by amending section

3.1 of the Schools Act to provide for the organization of both schools

and school districts on the basis of official language. Because of the geographic concentration of

the two language groups, this language-based structure was largely compatible

with a traditional territory-based administration. In one area, however, the bilingual Moncton region, a

French-language district and an English-language district occupied the same

territory.

This

act also provided for the creation of minority school boards in regions where

the population density was too low to justify the creation of a second

district. For example, an

English-language minority board was created to administer a single school in

the French-language district of Edmundston.

There are now a total of six French-language majority school boards in

New Brunswick, with responsibility for nearly 50,000 pupils and 145 schools.[19]

In

the decade following the commission's report, the question of French-language

education in the other English-speaking provinces became an increasingly

prominent political issue. Federal

language legislation, proclaiming as it did the official equality of English

and French, greatly enhanced the social and political status of the French

language in the country as a whole; but it could not extend language equality

to education since this was a provincial responsibility. Federal declarations concerning the equal

status of the two languages appeared strikingly incongruous when confronted

with the reality: publicly-funded French-language schooling was virtually

non-existent outside Quebec and New Brunswick.

In

1976, when the Parti Québécois, a party seeking to create an independent

Quebec state, was swept to power in the provincial elections, political

attention was again focused on the crisis in French-English relations. The new Quebec government deliberately drew

attention to the harsh treatment of the French-speaking minority outside Quebec

and publicly compared it with the privileged situation of the English-speaking

minority in Quebec. French-language

education became a political issue associated with national unity and

constitutional reform.

In

1977, the ten provincial premiers, following a meeting in St. Andrews, New

Brunswick, issued a statement of support for minority-language education:

Recognizing our concern for maintenance and where

indicated, development of minority language rights in Canada; and recognizing

that education is the foundation on which language and culture rest; The

Premiers agree that they will make their best efforts to provide instruction in

education in English and French wherever numbers warrant.[20]

This consensus later found expression in section 23 of

the Constitution Act, 1982 where provision was made for minority

language educational rights (see Table 2).

For example, the French-speaking minority was guaranteed the right to

have their children educated in French, at both the primary and secondary

school level. More specifically, they

were entitled to ‘minority language educational facilities provided out of

public funds’ wherever the number of eligible children so warranted. Similar provision was made for the

English-speaking minority in Quebec.

Children

were entitled to receive a French-language education if their parents met any

one of three possible conditions: they were citizens of Canada who had French

as their mother tongue, or had received their primary school instruction in

French, or had a child who had received school instruction in French. Since French-language education was, until

this time, relatively rare in most of the English-majority provinces, the first

criteria, based on mother tongue, was generally the most relevant.

An

important issue, given the dispersion of French-speakers, was the

interpretation to be given to the qualification ‘where the number of those

children so warrants.’ This was

interpreted quite differently by each provincial government. In the primary schools, for example, the

right to French-language education in a school district was warranted to exist

if, in British Columbia, there were 10 pupils; in Manitoba, 23 pupils; in

Ontario, Nova Scotia or Prince Edward Island, 25 pupils; in New Brunswick, 30

pupils.[21] In general,

however, the courts were unwilling to set an exact number, claiming instead

that each case should be judged on its merits.

TABLE 2

MINORITY LANGUAGE EDUCATIONAL RIGHTS IN CANADA,

CANADIAN CHARTER OF RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS, 1982

Section 23.

(1) Citizens of Canada

(a) whose first language learned

and still understood is that of the English or French linguistic minority

population of the province in which they reside, or

(b) who have received their

primary school instruction in Canada in English or French and reside in a

province where the language in which they received that instruction is the

language of the English or French linguistic minority population of the

province, have the right to have their children receive primary and secondary

school instruction in that language in that province.

(2) Citizens of Canada of whom

any child has received or is receiving primary or secondary school instruction

in English or French in Canada, have the right to have all their children

receive primary and secondary school instruction in the same language.

(3) The right of citizens of

Canada under subsections (1) and (2) to have their children receive primary and

secondary school instruction in the language of the English or French

linguistic minority population of a province

(a) applies wherever in the

province the number of children of citizens

who have such a right is sufficient to warrant the provision to them out of

public funds of minority language instruction; and

(b) includes, where the number

of those children so warrants, the right to have them receive that instruction

in minority language educational facilities provided out of public funds.

Source. Canada, Department of Justice.

A Consolidation of the Constitution Acts 1867 to 1982

(Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services,

1989).

It

was not immediately obvious that the right to French-language schooling might

also include a guarantee of segmental autonomy. This question hinged on the interpretation given to the

expression ‘minority language educational facilities’ or, as the French text

indicated, ‘des établissements d'enseignement de la minorité linguistique’. The term ‘facilities’ appeared to refer

simply to a physical site while the expression ‘établissements de la

minorité’ seemed to imply a management structure. The fact that the Canadian parliament had explicitly chosen ‘établissements’

as a replacement for the more restrictive term ‘installations’ found in

the original French-language draft of the bill, underlined the significance of

this wording.

Several

minority group representatives had requested that the minority's right to

manage their schools be recognized in the constitution. However, Jean Chrétien, the minister of

justice at that time, did not support this request, arguing that the proposed

constitutional guarantee should not go beyond the provincial consensus; since

education was a provincial responsibility it was judged unwise for the federal

government to impose its views in the matter.

In proposing that the bill be amended to include the term ‘établissements’,

Chrétien suggested simply that this would permit minority schools to adopt

modern educational technologies that extended beyond the walls of a specific

facility.[22] In any case,

it was to be left to the courts to ensure that the provinces did not

discriminate against the French-speaking minority and that schooling of equal

quality was made available.

The

courts supported a generous interpretation of minority- language education

rights. In 1984 the Ontario Court of

Appeal ruled, in the Education Act Reference, that s.23 implicitly

granted French-speakers the right to participation in the management and

control of their French-language educational facilities.[23] This right

would be realized if French-speaking representatives were given exclusive

authority over their facilities, including the responsibility for the

expenditure of funds and the appointment of administrators. In the view of the court, majority rule had

in the past led to unfortunate consequences, including the denial of French-language

schools. In 1987, the Alberta Court of

Appeal, in Mahé v. R., arrived at a similar conclusion when it asserted

the need for exclusive control by the French-speaking minority: ‘Any diminution

in that power inevitably dilutes the uniqueness of the school and opens it to

the influence of an insensitive if not hostile majority.’[24]

The

Supreme Court of Canada, in its 1990 judgment in the Mahé case, confirmed the

right of the French-speaking minority in Canada (and the English-speaking

minority in Quebec) to manage and control its schools. Where the number of students was sufficient,

the court ruled that the required degree of control could be attained through

the creation of an independent French-language school board. Otherwise, the condition could be met by the

representation of the French-speaking minority within an existing school

board. Even in this latter case,

however, the minority was to be given exclusive power for decisions pertaining

to instruction in its French-language schools, including: the expenditure of

funds for these schools; the appointment and the supervision of administrators

in these schools; the establishment of school programmes; the recruitment and

the placement of personnel, particularly teachers; and the concluding of agreements

for teaching minority students and for providing services.[25] The public

funds provided must be sufficient to ensure that the schooling given the

French-speaking minority is equal in quality to that given the majority.

Clearly,

then, the Canadian constitution guarantees the French-speaking minority

significant autonomy in the control of its schools although this autonomy may

be accomplished using various management models. Most provinces, however, were recalcitrant in granting this

autonomy and yielded only when so obligated by the courts, following litigation

by the French-speaking minority. At the

time of the Supreme Court decision in the Mahé case in 1990, the most common

management model was the optional advisory committee.[26] These

committees were composed of French-speaking parents and established at the

discretion of the English-language school board. They existed in six provinces but had only a consultative role;

they did not give the minority decision-making power.

As we

have noted, the first autonomous French-language school boards were created in

New Brunswick in 1981, i.e., before the adoption of the constitutional

amendment guaranteeing minority language educational rights. Ontario followed next with the creation of

French-language school boards for Metropolitan Toronto and Ottawa-Carleton in

1989, and for Prescott-Russell in 1991.

Elsewhere in the province, however, responsibility for French-language

schools belongs to English-language school boards, although it is shared with

their French-language sections or advisory committees. Prince Edward Island created a province-wide

French-language school board in 1990.

Nova Scotia established a French-language school board for Halifax in

1992, but the situation remains unresolved in other regions of the

province. The western provinces of

Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba each created French-language school boards

in 1994. Alberta established three

French-language school boards and three coordinating councils, while

Saskatchewan established eight French-language school boards. Manitoba, on the other hand, established a

province-wide Franco-Manitoban School Division regrouping 20 schools and 4,200

students.[27] No agreement

has yet been reached concerning French-language school boards in British

Colombia or Newfoundland.

It is

not feasible to examine each of these cases in detail. However, the Alberta situation will be

studied further in order to cast light on the characteristics of the

newly-established French-language school boards, as well as the conditions

leading to their creation. This will

allow a better understanding of the segmental autonomy granted to Canada's

dispersed French-speaking minority.

Alberta

The Alberta government supported the principle

of French-language minority schools in 1977 at St. Andrews and subsequently

approved the 1982 amendment to the Canadian constitution. Nevertheless, it vigorously resisted the

actual establishment of these schools in the province.

In

its policy statement on minority language instruction, formally announced in

1978, the government explained that French-language instruction might be

offered, but it was to be open to all language groups. Alberta refused to make a distinction

between a French immersion school, where French was taught to English-speakers,

and a French minority school, where French was taught to French-speakers: ‘It

will continue to be our policy to allow admission to French language programmes

regardless of mother-tongue.’[28] The result,

given the minority status of French-speakers and the widespread interest among

English-speakers for French instruction, was that Alberta's French-language

schools were, in reality, French immersion schools. The schools were largely oriented to English-speakers and became

yet another instrument for assimilating the French-speaking minority. In 1981-82, when the Canadian constitution

was amended, there were 13,131 students registered in Alberta's French-language

schools. It is doubtful that more than

20 per cent of these were native French-speakers.

In

1982 a group of French-speaking parents in Edmonton contacted, first, the

minister of education and then, subsequently, the Edmonton Public School Board

and the Edmonton Catholic School Board, to request a French-language minority

school. When this request was refused,

the parents took their case to court claiming that the province's School Act

contravened s.23 of the Constitution Act, 1982. In the Mahé case, the Alberta Court of

Queen's Bench supported the parents and, in 1985, it ordered the province to

make specific provision for French-language minority schools. The province agreed to recognize minority

schools, as distinct from immersion schools and, in 1988, adopted a new School

Act that provided an explicit declaration of the right of the

French-speaking minority to school instruction in French.

The

new School Act still did not provide for the management of these schools

by the French-speaking minority, however, and the parents of the Bugnet

Association continued their court battle.

In 1990, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled, as noted earlier, that

French-speakers were entitled to manage and control their schools. French-language schools that were not

managed by the French-speaking minority were not true minority schools and did

not meet the standards imposed by the constitution. The court ordered the province to enact legislation that would

put into place a minority language education scheme consistent with s.23 of the

charter.

The

provincial government reacted negatively to this decision and it threatened to

override the minority guarantee by using the constitution's so-called

`notwithstanding' clause. When advised

that this clause was not applicable to s.23, the government reluctantly

produced a working paper that reviewed the key points of the court decision and

examined two different models of school management.[29] In 1991 it

appointed a French Language Working Group, chaired by a member of the

legislative assembly and composed of nine members representing the principal

stakeholders, including the French-speaking population. This group was charged with making

recommendations for a management model that would meet the criteria set out by

the Supreme Court and that would be relevant to the situation in Alberta. Its recommendations were unanimous and, a

year later, the minister of education appointed a Francophone School Governance

Implementation Committee, chaired by an assistant deputy minister and composed

of seven other members. The committee's

mandate was to propose a strategy for the implementation of the working group's

recommendations. Finally, in 1993, the

legislative assembly adopted an amendment to the School Act that

provided for minority school boards and coordinating councils. These were established in 1994.

The

Alberta government had doggedly resisted the introduction of French-language

minority schools for many years.

However, following the Supreme Court decision in 1990, it initiated

school reforms that were consistent with the constitutional guarantees and with

Alberta's particular situation.

Significantly, these reforms were developed in close consultation with

the French-speaking population of the province.

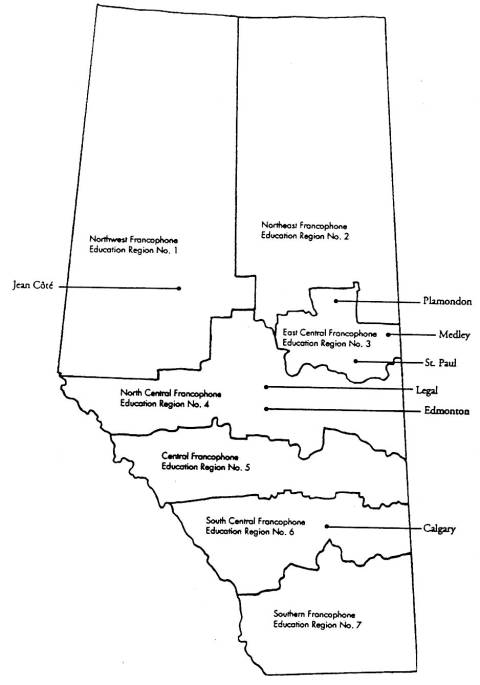

An

important feature of the new school system was the creation of seven new school

districts, described in the newly-amended School Act as Francophone Education

Regions (see Figure 2.) The decision to

create a regional system, rather than one province-wide system, reflected a

consensus in the French-speaking community that a regional system would provide

closer links with the population, thus ensuring: greater popular participation,

more efficient response to different needs and better delivery of services. In general, it was felt that such a system

would be more democratic and more sensitive to regional differences within the

province.[30]

FIGURE 2

MAP OF FRANCOPHONE EDUCATION REGIONS IN ALBERTA, 1994

Note. The cities and towns marked on

the map are communities that currently possess French-language schools.

Source. Guide de mise en oeuvre de la gestion scolaire francophone

(Edmonton: Alberta Education, School Business Administration Services, 1994),

p. 8.

Given the size of the province and the distribution of

its French-speaking population, a regional system was an appropriate

choice. The province of Alberta has an

area of 661,190 sq. km., making it 16 per cent larger than France. On average, each of the new education

regions is three times the size of Belgium and more than twice the size of

Estonia. Further, the French-speaking

population in Alberta, like that in Saskatchewan, is not concentrated in any

one region of the province. This

contrasts considerably with the situation in Manitoba or in Prince Edward

Island, where there is greater concentration and where province-wide districts

were created. In Prince Edward Island,

for example, the original French-language school board had jurisdiction only

for the Evangeline Region, home to the great majority of the province's French-speakers. Later, at the request of the French-speaking

minority, the board's jurisdiction was extended to all French-speakers,

whatever their place of residence, thereby giving the board province-wide

authority.

TABLE

3

STUDENTS ENROLLED IN ALBERTA SCHOOLS,

BY FRANCOPHONE EDUCATION REGION, 1993

|

Francophone |

|

Students |

Students |

Students |

|

||

|

Education |

Urban |

enrolled in |

eligible for |

enrolled in |

French |

||

|

Region |

centre |

all schools |

French schools |

French schools |

schools |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No. 1 |

Peace River |

29,838 |

2,420 |

8.1 |

265 |

0.9 |

1 |

|

No. 2 |

Fort McMurray |

9,239 |

525 |

5.7 |

60 |

1.5 |

1 |

|

No. 3 |

St. Paul |

14,836 |

2,435 |

16.4 |

362 |

2.4 |

3 |

|

No. 4 |

Edmonton |

197,581 |

9,895 |

5.0 |

951 |

0.5 |

5 |

|

No. 5 |

Red Deer |

34,550 |

925 |

2.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

|

No. 6 |

Calgary |

155,789 |

4,810 |

3.1 |

434 |

0.1 |

2 |

|

No. 7 |

Lethbridge |

43,678 |

860 |

2.0 |

33 |

0.4 |

1 |

|

Total |

|

485,511 |

21,870 |

4.5 |

2,105 |

0.4 |

13 |

Note. The figures for student enrollments are for grades one through

twelve in publicly-supported schools as of 30 September 1993. The 17,103 students enrolled in private

schools are not included. The number of

students eligible for French-language schooling under s.23 is an estimate

calculated from the 1991 census results.

It measures the number of students, ages five to seventeen, who have a

French-speaking mother or father.

Sources. Calculated from: `Inscriptions

dans les écoles francophones de l'Alberta', Le Chaînon: Bulletin

d'information de la Fédération des parents francophones de l'Alberta v7 n2

(1993), p. 3; Enrollments by School

and Grade within Original Jurisdiction as at September 30, 1993 (Edmonton:

Alberta Education, Grants Planning and Administration Branch, 1993); Guide

de mise en oeuvre de la gestion scolaire francophone (Edmonton: Alberta

Education, School Business Administration Services, 1994), p. 10.

The regional system adopted in

Alberta was generally preferred to another possible alternative: a system based

on a large number of small local districts.

It was feared that if the districts were too small, the population base

would also be too small; it would be difficult to create educational

institutions comparable to those of the majority. Further, the choice of a regional system was consistent with the

provincial government's announced intention to amalgamate smaller school

districts and to establish larger regional divisions. (The number of English-language districts was subsequently

reduced from 146 to 57.)

The

Francophone Education Regions are a realistic reflection of the geographic

distribution of the French-speaking minority.

Examination of the distribution map (see Figure 1) shows that the great

majority of the province's French-speakers are located in four major areas of

the province. These are: Edmonton,

Calgary, St.Paul-Bonnyville and Peace River-Fahler. There are also smaller populations in Red Deer, Fort McMurray and

Lethbridge. These various urban

clusters provide natural centres for education regions that encompass the

entire province (see Table 3).

The

amended School Act also provided for the creation of Francophone

Regional Authorities in each region, that is, French-language school

boards. (According to s.6, any

reference in the law to a school board is deemed to apply to a regional

authority.) The new authorities were mandated

to manage and control the French minority schools of their region. This includes responsibility for: tracking

eligible students and facilitating their education in French, representing

French-speaking parents, promoting French-language instruction in the province,

maintaining links with other regional authorities, and developing rules and

regulations for French education.[31] As school

boards, they were also empowered, by the School Act, to: establish

policies for the provision of educational services and programmes; offer

courses, programmes and instructional materials for use in schools; to employ

teachers and non-teaching personnel including administrators and supervisors;

to maintain and furnish their real property; to make rules respecting the

attendance and transportation of students and, generally, all matters within

their jurisdiction.

Each

regional authority is composed of five members elected by the French-speaking

population of the region. The School

Act grants voting rights, first and foremost, to the parents of students

registered in the minority schools of the region. However, it also authorizes the minister of education to extend

the franchise to other French-speakers, particularly those whose children are

eligible for the minority schools, even if these children are not yet (or are

no longer) registered. The first

elections were organized in 1994 by the Fédération des parents francophones

de l'Alberta. Subsequent elections,

held in October 1995 and then every three years thereafter, are the

responsibility of the regional authority.

The

amended School Act also provides, in section 223.3, for the transfer of

the necessary facilities and employees from the existing school boards to the

new regional authorities. It is

incumbent on the boards and the authorities to negotiate the transfer of this

property; however, the minister reserves the right to intervene where no

agreement is reached within three months.

In 1994, employees in the minority schools were free to transfer to the

new authority or to remain with their existing board. The authorities were required to respect the employment contracts

currently in effect until their normal expiry.

Where the property and the employees were already closely identified

with the French minority schools, these transfers generally took place without

incident. Other cases were more

controversial. For example, in St.

Paul, where the existing French minority school was badly overcrowded, the

regional authority requested the transfer of an English-language school

attended, in great majority, by students eligible for the French minority

programme. The school board refused

this request and the minister of education was forced to settle the issue. A new French minority school will be

constructed.

In

1994 the school boards lost their traditional power to levy school taxes. This had been the source of 42 per cent of

their income in 1993. These taxes are

now to be collected solely by the provincial government and then redistributed

proportionately according to the number of students served by the board. School boards currently receive a provincial

grant of about $4,200 per student for school maintenance and teaching. Additional grants are determined by the

specific characteristics of the district, including its size, population density,

student needs and programme costs. Thus,

for example, in 1994-95, regional authorities received a further grant of $332

per elementary student and $406 per secondary student to meet the costs of

French-language instruction.[32] As the result

of an agreement signed with the Government of Canada in October 1993, the

Government of Alberta received federal funding to assist the implementation of

the new French-language school system. It received, for example, federal grants

of $5.4 million for school management costs, $6.4 million for programme development

and $4.5 million for school construction.[33]

In

planning the management of minority education in Alberta, the provincial

government had considered two possible models.[34] The first

model, a `designated positions' model, would have reserved places for

French-speaking trustees on existing English-language school boards. The second model, a `regional board' model,

proposed the creation of new French-language school boards in regions where

there were large numbers of French-speaking students. Both models would have met the standards imposed by the Supreme

Court in the Mahé case. However, the

major interest groups, the Fédération des parents francophones de l'Alberta,

the Alberta School Trustees Association and the Alberta Teachers Association,

all gave their support to the second model.

Consequently, the government decided, with some reluctance, that the

`regional board' model would be `more workable.' Compared to its alternative, this model seemed likely to ensure

that, in the future, disputes between English and French trustees over

jurisdiction and rôles would be avoided.

The

new regional authorities were intended for regions where there were a

sufficient number of minority students.

Nevertheless, the actual establishment of an authority by the minister

of education was to be made at the request of the region's French-speaking

parents. Four regions, centred in

Edmonton, Calgary, St. Paul and Peace River, appeared to meet the required

minimum for students (see Table 3).

However, French-speakers in Calgary opposed the immediate creation of a

regional authority, undoubtedly because it would have jeopardized the Roman

Catholic School Board's plan to construct a new French minority school and

community centre. Thus, only three

regional authorities were established in 1994.

Francophone

Coordinating Councils were established in Calgary and in the two other regions

where there were French minority schools.

The amended School Act charged the councils, in section 223.7, to

facilitate the French-language education of minority students and to advise

school boards on all matters relating to this education. The councils lacked the autonomy granted to

the school boards, but they were clearly expected to be a temporary measure. If successful in expanding French-language

instruction in the region, the councils would contribute to their own demise:

they would be dissolved, to be replaced by a regional authority.

Alberta's

French-language school boards have been in operation for less than a year and a

full assessment is undoubtedly premature.

Some preliminary observations may be made, however. First, it is evident that, by freeing the

French minority schools from English-language school boards, the potential for

English-French tensions has been significantly reduced. This is particularly true in the Edmonton

region where disputes over minority schools have marred relations for more than

a decade. Second, it appears that

French-language schooling will now be more responsive to the needs of the

French-speaking community. This

community is now able to take a more active role in the development of its

education and to provide a wider-range of French-language educational services.

Significant

problems remain. While the granting of

minority education rights was clearly intended to repair past injustice, the

clock cannot be turned back. The great

majority of French-speakers in Alberta were, until recently, educated in

English. Their children often speak

English as their mother tongue. It is

estimated that only 20 per cent of those students who are eligible for minority

schooling, as guaranteed by s.23, are in fact native French-speakers.[35] The

English-speaking children of French-speaking parents are more likely to be

registered in French immersion schools, than in French minority schools.[36] Nevertheless,

these children pose a particular dilemma for the French-language school boards.

For

many French-speaking Albertans, religion is as important as language in

defining their cultural values. Most

French-speakers are also Roman Catholic and most French-language schools were,

until 1994, governed by Roman Catholic separate school boards. In the battle for French-language schools,

some French-speakers have seen separate English and French educational systems

as creating an undesirable schism within the Catholic community. Other French-speakers, a minority, have

actively sought the creation of non-denominational French-language

schools. The first major decision

facing the new regional authorities has been the determination of their

denominational status. In Edmonton, the

authority has chosen a Roman Catholic identity.

It

should also be noted that the autonomy accorded the regional authorities and,

indeed, all school boards, has limits.

Ultimate responsibility for education remains with the provincial

government, and with the minister of education. This includes, for example, the right to collect school taxes, to

certify teachers and to determine curriculum.

French-speakers generally lack autonomy within Alberta Education,

although a separate branch, the Language Services Branch, exists to provide

support to French-language and other non-English schools. Consequently, the French-speaking community

has called for the creation of a separate Francophone Division responsible for

French minority schooling.[37] This

division, to be headed by an assistant deputy minister, would ensure that

French-speakers have even greater control of their education system. A similar, but more comprehensive reform,

was adopted in New Brunswick in 1981 when the ministry of education was divided

into separate French and English sections, each headed by a deputy minister.

Conclusion

The

Canadian experience suggests that it is difficult for a dispersed minority to

obtain segmental autonomy. Many

provincial governments effectively banned French-language instruction until the

1960s. A combination of political

events, notably the statutory recognition of French as an official language in

1968 and the electoral victory of an independence party in Quebec in 1976,

contributed to the constitutional reform that guaranteed minority schools in

1982. This constitutional guarantee was

the all-important step on a tortuous path, marked by frequent litigation, that

is only now culminating in the establishment of French-language school

boards. Nevertheless, in most cases,

this autonomy was conceded by the provinces under duress. Segmental autonomy was implemented because

it was ordered by the courts.

A

recent referendum in Quebec has raised some questions as to the future of

Canada's French-speaking minority and their constitutionally-guaranteed

language rights. In a referendum held

on 30 October 1995, Quebecers narrowly defeated (50.6% to 49.4%) a proposition

to create an independent Quebec state.

The narrowness of this margin has convinced many that the future

separation of Quebec is inevitable.

Further, the governing Parti Québécois is committed to a third

referendum on this question. (In the

first referendum, held in May 1980, a government proposition to negotiate

independence while continuing political association, a regime described as

Sovereignty-Association, was defeated 60% to 40%.) If Quebec became independent, would Canada maintain its

constitutional guarantees for the French language?

In a

Canada without Quebec, the remaining one million French-speakers would

constitute only 5.2 per cent of the population. Although they would still be the country's largest language

minority, some analysts suggest that their numbers would be too small to justify

their current constitutional rights, particularly in the face of an

English-speaking majority angry at the break-up its country. According to Roger Gibbons: ‘The francophone population, stripped of the

political protection afforded by Quebec, would be too small to warrant

constitutional protection . . . . In

all probability, the official-languages sections of the Charter of Rights and

Freedoms would be repealed at the first opportunity.’[38]

It is

difficult to predict the full consequences of the possible break-up of

Canada. Certainly, there are other

countries where language minorities have achieved official recognition even

though they number less than five per cent of the population (and much less

than one million persons). Switzerland,

for example, has long recognized Italian as a national language (since 1874)

and as an official language (since 1938), although today only 4.5 per cent (and

less than a quarter-million) of its citizens are Italian-speaking. Nevertheless, the Italian-speakers are not a

dispersed minority: the great majority live in the canton of Ticino.

Estonia

adopted a Law on the Cultural Self-Government of National Minorities in

1925 that permitted the German, Russian, Swedish and Jewish minorities (indeed,

any minority numbering at least 3,000, i.e. about 0.2 per cent of the

population) to control their cultural and educational institutions.[39] The most

dispersed minorities, the Germans and the Jews, availed themselves of this

opportunity, although they numbered only 1.8 per cent and 0.4 per cent,

respectively, of the total population.

Latvia similarly recognized the autonomy of its dispersed minorities, in

1919, although this was limited to educational institutions.

The

Estonian and Latvian examples suggest that it is not impossible for a small,

dispersed minority to obtain segmental autonomy in the field of education. While the recent establishment of Canada's

French-language school boards owes much to the demographic and political

importance of Quebec, its justification does not disappear with the possible

separation of Quebec from the Canadian federation. Further, the advantages of these school boards become even more

apparent as they become increasingly well-established. Indeed, at this point, any attempt to

eliminate French-language schools would entail substantial financial and social

costs. Nevertheless, as some observers

have commented, it is impossible to guarantee the good humour of a couple

involved in divorce proceedings. In the

event of Quebec's separation, French-language schools might be targeted by a

vengeful English-speaking majority.

Education

is an area of critical concern to the French-speaking minority. The granting of limited autonomy in this

area constitutes an interesting application of a consociational strategy. For the minority, it provides greater

democratic participation, increased security from arbitrary decisions and, in

general, new hope for the future. The

longer term effects on English-French relations remain to be seen. A similar model for minority autonomy could

by applied to other areas, notably cultural and health services. In the current political context, however,

this seems improbable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

An earlier version of

this article was presented at the Conference on the Governance of Dispersed

Ethnic Groups held at the University of Ottawa on 3 June 1995. I would like to thank Jean Laponce for his

kind invitation to present a paper at this conference. I am also grateful to my colleagues France

Levasseur-Ouimet and Frank McMahon for their helpful comments on French

minority education in Alberta; and to Francine Roy for her capable assistance

with the preparation of the tables.

NOTES