For Engl 100:D1 Feb 12-16 2001

For a concise biography, see Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 35. Victorian poets after 1850. PR 591 V6455 1985 Rutherford N. Reference

Christina Rossetti: A Chronology, The Victorian Web

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, The Victorian Web

Pre-Raphaelite Women, Kathleen L. Nichols (note that this if the 3rd of 4 sections; you can click back and forward from here for much more on the Pre-Raphaelites)

Anthony H. Harrison, Christina Rossetti in Context (1988), Chapter 4, part 2

Throughout much Pre-Raphaelite love poetry, a dialectic of desire and renunciation is at work thematically. Whether a depicted passion is visceral or idealized, its object and therefore any fulfillment of desire are almost always unattainable. As a result, the finest poetry of Christina and Dante Rossetti, of Morris and Swinburne, is essentially elegiac: melancholy poetry of intense unsatisfied longing, of unrealized potential, and of loss. The emotional malaise characteristic of Pre-Raphaelite poetic personae prompts most of them eventually to renounce the quest for fulfillment in this world in favor of attaining it in a concretely envisioned afterlife, or in some surrogate form (usually a dream), or in art itself. As I have already observed, the Pre-Raphaelite love poem often becomes a self-conscious emblem of accomplished perfection -- of the ideal itself -- and of the sense of fulfillment that its contents may, nevertheless, describe as impossible to attain. Art in this way achieves transcendence "outside" the mutable world. Even in the most sensual Pre-Raphaelite poems, such as Swinburne's Anactoria, where the poet Sappho speaks, the poetic enterprise assuages the longings of personae who often are themselves artists. Ironically, therefore, this school of poets whom James Buchanan labeled "fleshly" usually depicts desires and pleasures of the flesh only in order ultimately to expose their futility except as passports to a superior and transcendent ideal realm and as inspirations for art, in which the torturous ardors of human passion come most attractively to fruition.

Pre-Raphaelite poetry often thus focuses on the impossibility or transience of promised fulfillment in this world, but also, and as an unexpected corollary, on a speaker's or central character's ultimate sense of inadequacy or unworthiness to achieve a desired fulfillment. It cultivates a tone of languorous melancholy, fully exploiting the elegiac potential of its materials, and is frequently described by contemporary reviewers as "morbid."

* * * * *

Just as tracing Christina Rossetti's uses of Dante and Petrarch will illuminate the ways in which the Pre-Raphaelites exploit literary tradition, closely reading her poems of renunciation in the context of her literary and philosophical models can reveal much about a central psychological impulse in Pre-Raphaelite poetry and the aestheticist effects of that impulse. Such exegesis also enables us more fully to understand the emotional and intellectual responses Pre-Raphaelite poetry generates within the reader. These crystallize into a distanced perception of the poem as a thing of beauty which makes use of the sensations and experiences of quotidian reality primarily to withdraw from that reality and create an estranged and static world of art.

Rossetti's artistry

From Christina Rossetti and the Poetic Vocation, in Harrison

As we know, Dante Rossetti, the reluctant aesthete, was the most frequent and effective critic of his sister's manuscript poems. Christina alluded to him repeatedly as her mentor, and, as the revisions of "Maude Clare" suggest, she was, like him, ultimately more interested in the quality and effectiveness of a poem than in conveying themes or in being sincere and self-expressive. The extent to which artistic perfection was the preeminent concern in Christina Rossetti's poetry, as it was in her brother's, was perceived by early commentators like Arthur Symons, Virginia Woolf, and Justine DeWilde but has been ignored by most of her critics for the last fifty years.(See Symons, "Christina Rossetti," in Two Literatures, 48; Woolf, Second Common Reader, 264; and DeWilde, Christina Rossetti.) Yet her irrepressible concern with the artistry of her works and with her own artistic vocation is unmistakable in her early letters. After her grandfather Polidori printed two volumes of her childhood poems, one in 1842 when she was twelve years old and one in 1847; after she succeeded in placing two poems in the Athenaeum in 1848; and after seven of her works appeared pseudonymously in The Germ during 1850, [12/13] Rossetti subsequently endured a frustrating hiatus in her publishing career. From 1851 until 1861 she saw only two of her poems and one short story appear in print, despite the self-confidence of her letters of submission to potential publishers.

Catherine Belsey, Is C. Rossetti's "Goblin Market" Escapist?

Belsey sees the poem as a feminist satire on "Tristan and Iseult."

Clifton Snider, "There is No Friend like a Sister": Psychic Integration in Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market.

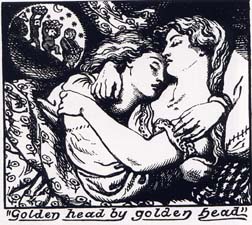

Fig.

2, drawing by D. G. Rossetti for the cover of Goblin Market and Other Poems

(1862), his sister, Christina's first book of poems.

Fig.

2, drawing by D. G. Rossetti for the cover of Goblin Market and Other Poems

(1862), his sister, Christina's first book of poems.

Document created February 11th 2001