From Julius Caesar Ibbetson, John Laporte, and John Hassell, A Picturesque

Guide to Bath, Bristol Hot-Wells, the River Avon, and the Adjacent Country.

London: Hookham and Carpenter, 1793. Illustration included.

<P 245> The Wye, at Monmouth, does not exhibit such romantic scenes as about Chepstow; yet those who can visit it during the spring-tides will find ample compensation for their trouble, in the pleasure of going by water from Chepstow to Monmouth, and back again. By land, there is not a single object till we reach Tintern abbey that deserves notice.

As we declined hence towards Tintern, the road was obstructed by great quantities <P 246> of loose stones laid on it, and rills of water crossing it at small distances. We seemed now to be penetrating a gloom aptly suited to prepare the mind for the venerable object of our curiosity; but our contemplations were presently disturbed by the sight of a number of smelting-houses on the banks of the Wye, and much too near the abbey: clouds of thick black smoke, and an intolerable stench, issued from these buildings, disgusting to the utmost degree, and entirely destroying the landscape. Here and there we could discover a select spot that might have afforded a sketch, but we were disappointed and vexed. At the end of this road we come to a small inn, the landlord of which serves as keeper and guide to the ruins of Tintern abbey.

This beautiful ruin is situated in the lowest part of a small vale, encompassed with woods and rocks, some of which rise to the height of three hundred feet, and form the bed of the Wye: it is much to be regretted, that the hollow situation of the abbey prevents its being seen from the river.

<P

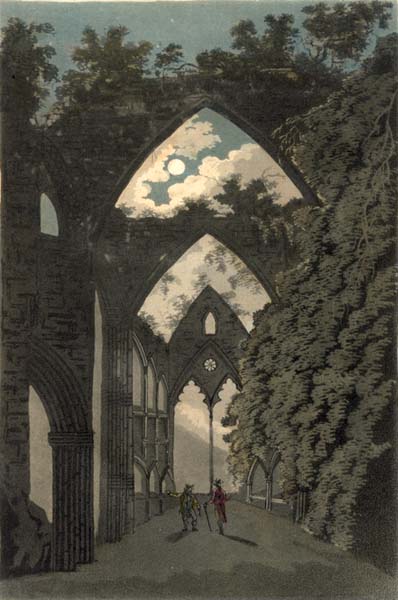

247> As we approached, the wretched inhabitants of some miserable hovels

presented themselves: neither the dwellings, nor the occupiers of them, were

at all in harmony with the grandeur of the scene we were considering. We entered

at the east gate, through a large arch, and saw all we had yet beheld of awful

magnificence, surpassed by the ruins of Tintern. Nothing fabricated by human

hands can be more sublime. The figure of the abbey is a cross: at the west

end is a large Gothic window of exquisite beauty: the windows and the pillars

that supported the roof, are in the purest style of this architecture. The

walls are all standing. The length of the nave is two hundred and thirty-one

feet, the breadth thirty-three. The cross aisle is one hundred and sixty feet

long.

<P

247> As we approached, the wretched inhabitants of some miserable hovels

presented themselves: neither the dwellings, nor the occupiers of them, were

at all in harmony with the grandeur of the scene we were considering. We entered

at the east gate, through a large arch, and saw all we had yet beheld of awful

magnificence, surpassed by the ruins of Tintern. Nothing fabricated by human

hands can be more sublime. The figure of the abbey is a cross: at the west

end is a large Gothic window of exquisite beauty: the windows and the pillars

that supported the roof, are in the purest style of this architecture. The

walls are all standing. The length of the nave is two hundred and thirty-one

feet, the breadth thirty-three. The cross aisle is one hundred and sixty feet

long.

Mr. Gilpin exclaims loudly against the effect of perfect gable-ends in a ruin, and laments that a chissel is not used to reduce them to a better form; but the experiment is dangerous. In Tintern abbey there are four gable-ends, that certainly give an air of stiffness <P 248> to the building; but we were much more disgusted with the stone walls that pass in oblique directions, and cut it off from the road, so that nothing but a bird's-eye view can give a correct delineation of the whole. The daws and martlets, which in great numbers have taken up their abode here, seem its proper inhabitants. On the authority of our immortal bard we may accept them as a token of the purity of the air; and the situation chosen by the martlet, brought forcibly to our recollection his description of their oeconomy:

'No coigne of vantage, jetting frieze, or buttrice,

But what this bird has made his pendent bed

And procreant cradle.'

MACBETH.

* * * * * *

<P 249>From Tintern abbey the road leads up a long shaded lane, and again enters the high-road from Monmouth to Chepstow.

<P 250> By water, we pass the abbey between tremendous high rocks, winding alternately round abrupt precipices and woody promontories. In this part of the river Wye there is a sameness of scenery. Two high promontories on each side sweeping behind each other, with a third interposed, so as to close up the view, are the general accompaniments; but though the forms are nearly the same, they are much diversified by wood and rock: in some places they stand several feet from the surface of the earth, and hang as if threatening all beneath them: distorted oaks and overgrown ash combine with the landscape in this seeming danger, and stand as if expecting every moment to be hurled to the bottom.