The two following extracts are from William Gilpin, Observations on the River Wye and several parts of South Wales, 2nd Ed. London: R. Blamire, 1789. Plates are from this edition. Click on graphics to enlarge. The first edition of Observations appeared in 1782; the journey which it reports occurred in 1770.

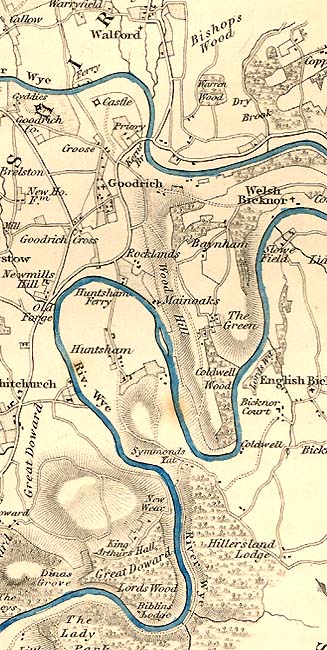

The map is from T. Roscoe, Wanderings and Excursions in South Wales including

the Scenery of the Wye. London: Tilt and Simpkin, 1837.

1. Goodrich Castle

<P 30> After sailing four miles from Ross, we came to Goodrich-castle; where a grand view presented itself; and we rested on our oars to examine it. A reach of the river, forming a noble bay, is spread before the eye. The bank, on the right, is steep, and covered with wood; beyond which a bold promontory shoots out, crowned with a castle, rising among trees.

This

view, which is one of the grandest on the river, I should not scruple to call

<P 31> correctly picturesque; which is seldom the character of

a purely natural scene.

Nature is always great in design. She is an admirable colourist also; and harmonizes tints with infinite variety, and beauty. But she is seldom so correct in composition, as to produce an harmonious whole. Either the foreground, or the background, is disproportioned: or some awkward line runs across the piece: or a tree is ill-placed: or a bank is formal: or something or other is not exactly what it should be. The case is, the immensity of nature is beyond human comprehension. She works on a vast scale; and, no doubt, harmoniously, if her schemes could be comprehended. The artist, the mean time, is confined to a span; and lays down his little rules, which he calls the principles of picturesque beauty, merely to adapt such diminutive parts of nature's surfaces to his own eye, as come within it's scope.

Hence therefore, the painter, who adheres strictly to the composition of nature, will rarely make a good picture. His picture must contain a whole: his archetype is but a part.

In general however he may obtain views of such parts of nature, as with the addition <P 32> of a few trees; or a little alteration in the foreground, (which is a liberty, that must always be allowed) may be adapted to his rules; though he is rarely so fortunate as to find a landscape completely satisfactory to him. In the scenery indeed at Goodrich-castle the parts are few; and the whole is a very simple exhibition. The complex scenes of nature are generally those, which the artist finds most refractory to his rules of composition.

In following the course of the Wye, which makes here one of it's boldest sweeps, we were carried almost round the castle, surveying it in a variety of forms. Many of the retrospects are good; but, in general, the castle loses, on this side, both it's own dignity, and the dignity of it's situation.

The views from the castle, were mentioned to us, as worth examining: but the rain was now set in, and would not permit us to land.

As we leave Goodrich-castle, the banks, on the left, which had hitherto contributed less <P 33> to entertain us, began now principally to attract our attention; rearing themselves gradually into grand steeps; sometimes covered with thick woods; and sometimes forming vast concave slopes of mere verdure; unadorned, except here and there, by a straggling tree: while the flocks, which hung browzing upon them, seen from the bottom, were diminished into white specks.

2. New Weir

<P 36> At Cold-well, the front screen first appears as a woody hill, swelling to a point. In a few minutes, it changes it's shape, and the woody hill becomes a lofty side-screen, on the right; while the front unfolds itself into a majestic piece of rock-scenery.

Here we should have gone on shore, and walked to the New-Weir, which by land is <P 37> only a mile; though by water, I believe, it is three times as far. This walk would have afforded us, we were informed, some very noble river-views: Nor should we have lost any thing by relinquishing the water; which in this part was uninteresting.

The whole of this information we should probably have found true; if the weather had permitted us to have profitted by it. The latter part of it was certainly well-founded: for the water-views, in this part, were very tame. We left the rocks, and precipices behind; exchanging them for low-banks, and sedges.

But

the grand scenery soon returned. We approached it however gradually. The views

at White-church were an introduction to it. Here we sailed through

a long reach of hills; whose sloping sides were covered with large, lumpish,

detached stones; which seemed, in a course of years, to have rolled from a

girdle of rocks, that surrounds the upper regions of these high grounds on

both sides of the river; but particularly on the left.

But

the grand scenery soon returned. We approached it however gradually. The views

at White-church were an introduction to it. Here we sailed through

a long reach of hills; whose sloping sides were covered with large, lumpish,

detached stones; which seemed, in a course of years, to have rolled from a

girdle of rocks, that surrounds the upper regions of these high grounds on

both sides of the river; but particularly on the left.

<P 38> From these rocks we soon approached the New-Weir; which may be called the second grand scene on the Wye.

The river is wider, than usual, in this part; and takes a sweep round a towering promontory of rock; which forms the side-screen on the left; and is the grand feature of the view. It is not a broad, fractured face of rock; but rather a woody hill, from which large projections, in two or three places, burst out; rudely hung with twisting branches, and shaggy furniture; which, like mane round the lion's head, give a more savage air to these wild exhibitions of nature. Near the top a pointed fragment of solitary rock, rising above the rest, has rather a fantastic appearance: but it is not without it's effect in marking the scene.

A great master in landscape has adorned an imaginary view with a circumstance exactly similar:

Stabat acuta silex, praecisis undiq; saxis,

---- dorso insurgens, altissima visu,

Dirarum nidis domus opportuna volucrum,

---- prona jugo, laevum uncumbebat ad amnem. [Aen. VIII. 233][On the left of the river stood a lofty rock, as if hewn from the quarry, hanging over the precipice, haunted by birds of prey. -- Gilpin's translation.]

<P

39> On the right side of the river, the bank forms a woody amphitheatre,

following the course of the stream round the promontory. It's lower skirts

are adorned with a hamlet; in the midst of which, volumes of thick smoke,

thrown up at intervals, from an iron-forge, as it's fires receive fresh fuel,

add double grandeur to the scene.

But what peculiarly marks this view, is a circumstance on the water. The whole river, at this place, makes a precipitate fall; of no great height indeed; but enough to merit the title of a cascade: tho to the eye above the stream, it is an object of no consequence. In all the scenes we had yet passed, the water moving with a slow, and solemn pace, the objects around kept time, as it were, with it; and every steep, and every rock, which hung over the river, was solemn, tranquil, and majestic. But here, the violence of the stream, and the roaring of the waters, impressed a new character on the scene: all was agitation, and uproar; and every steep, and every rock stared with wildness, and terror.

<P 41> Below the New-Weir are other rocky views of the same kind, though less beautiful. But description flags in running over such a monotony of terms. High, low, steep, woody, rocky, and a few others, are all the colours of language we have, to describe scenes; in which there are infinite gradations; and, amidst some general sameness, infinite peculiarities.

After we had passed a few of these scenes, the hills gradually descend into Monmouth; which lies too low to make any appearance from the water: but on landing, we found it a pleasant town, and neatly built. The townhouse, and church, are both handsome.