From William Coxe, An Historical Tour in Monmouthshire. London: T. Cadell & W. Davies, 1801. Extracts are from Volume 2. Illustrations are by Sir Richard Hoare. (Click on illustrations to enlarge.) NB. Several footnotes have been omitted.

William Coxe (1747-1828) was born in London and educated there and at Eton and Cambridge. After being ordained in 1771 he was briefly a curate at Uxbridge, but then travelled in Europe as a tutor, including visits to Switzerland, Hungary and Russia. He published Sketches of Swisserland in 1779 (which Wordsworth appears to have followed for his 1790 walking tour). In addition to this historical study of Monmouthshire, he also published accounts of travels in Poland, Russia, Sweden, and Denmark. He held livings at Bemerton near Salisbury from 1788 and Stourton from 1800-1811, and Fovant in Wiltshire.

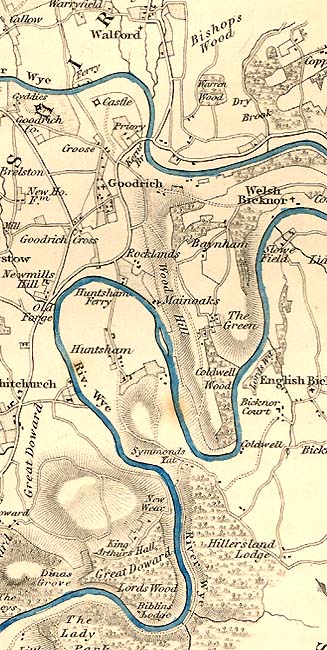

The map below is an extract from T. Roscoe, Wanderings and Excursions in South Wales including the Scenery of the Wye. London: Tilt and Simpkin, 1837.

<P 340>

Chapter 35.

To avoid digressions, I have hitherto solely confined my observations to Monmouthshire; yet as the voyage down the Wy, from Ross to Chepstow, is an interesting object, I shall in this single instance deviate from my original plan, and give a general account of the whole navigation; although that part of the river which flows from Ross to Monmouth is principally included in the counties of Glocester and Hereford. In company with Mr. Hoare, I went in a post chaise [from Monmouth] to Ross; the road runs near the right bank of the Wy, leaves Dixon church to the east, and after passing the frontiers, quits the river, and rejoins it beyond Goodrich, at a little distance from Ross, where we arrived in the evening, and on the following morning commenced our excursion down the Wy.

The characteristics of the Wy are its serpentine course, from which it is supposed to derive its name; the uniform breadth of the channel; and the scenery of its banks.

<P 341> The serpentine course is so considerable, that the distance from Ross to Chepstow, which in a direct line is not more than sixteen miles and four furlongs, is thirty-seven miles and seven furlongs by water. The effects of these numerous windings are various and striking; the same objects present themselves, are lost and recovered with different accompaniments, and in different points of view: thus the ruins of a castle, hamlets embosomed in trees, the spire of a church bursting from the wood, forges impending over the water, and broken masses of rock fringed with herbage, sometimes are seen on one side, sometimes on the other, and form the fore ground or back ground of a landscape. Thus also the river itself here stretches in a continuous line, there waves in a curve, between gentle slopes and fertile meadows, or is suddenly concealed in a deep abyss, under the gloom of impending woods.

Another characteristic of the Wy, is the almost uniform breadth of the channel, which seems to have been scooped by the hand of nature, in the midst of surrounding hills. Hence in the whole course of this navigation, except in the vicinity of Ross and till it receives the tide, the stream, unlike other mountain torrents, is not scattered over a wide and stony bed, but rolls in one compact and accumulated body. This uniformity of breadth is however broken by the perpetual sinuosity of the river, and enlivened by the diversified scenery of the banks, which forms the third characteristic of the Wy.

The banks for the most part rise abruptly from the edge of the water, and are clothed with forests, or broken into cliffs. In some places they approach so near, that the river occupies the whole intermediate space, and nothing <P 342> is seen but wood, rocks, and water; in others, they alternately recede, and the eye catches an occasional glimpse of hamlets, ruins, and detached buildings, partly seated on the margin of the stream, and partly scattered on the rising grounds. The general character of the scenery, however, is wildness and solitude; and if we except the populous district of Monmouth, no river perhaps flows for so long a course through a well cultivated country, the banks of which exhibit so few habitations.

We embarked at seven in the morning in a convenient vessel, capable of containing eight persons besides the boatmen, and provided with an awning, which as the weather was unclouded and sultry, we found a good defence against the rays of an August sun. We passed under the stone bridge, leaving on our right the ruins of Wilton Castle, and as the water was low, saw but few objects worthy of attention, except the spire of Ross church towering above the trees, and Penyard hill covered with wood.*

At a small farm called Weir End, the river turns abruptly, and flows under the precipitous sides of Pencraig hill mantled with trees to the margin of the river. From this place commences that interesting combination of scenery, which distinguishes the banks of the Wy. We soon afterwards descried the embattled turrets of Goodrich Castle; the first view of these ruins, which present themselves at a sudden bend in the river, crowning the summit of an eminence clothed with wood, is extremely grand and interesting; they vanish and reappear at different intervals, and as we passed under them assumed a less majestic, but a more picturesque aspect.

Having breakfasted at a ferry-house, at the foot of the hill on which the castle is situated, we ascended the steep sides of the acclivity, through rich groves of oak and elm, to the ruins, which on our approach reassumed their former grandeur. I shall not attempt to describe these remains, or to detail their history; but refer the reader to an accurate description, illustrated with a ground plot, and several interesting views, published by Bonnor.* I shall only observe, that among <P 343> all the accounts of the castle given to the public, William Herbert, earl of Pembroke is not mentioned as a proprietor, although he obtained from Edward the fourth, among many other possessions, the castle and manor of Goodrich, with the lordship and manor Urchenfield.

Descending form the castle, we passed through some pleasant meadows to a farm house, once the site of a priory, and traced, in the gothic windows and part of the chapel, the remains of the ancient structure.

Re-embarking, we continued our course, and were gently carried down the stream by the current. The scenery is mild and placid, the river is bounded on each side by wooded acclivities, above which to the left towers the spire of Ruerdean church peeping from the midst of the forest, and near Lidbrook the slopes of the hills are thickly sprinkled with cottages, delightfully situated in the midst of surrounding copses. From Lidbrook large quantities of coal are sent to Ross and Hereford; and we passed several barges towed by ten or eleven men, which by great exertions are drawn to Hereford in two days. Hitherto the county of Hereford uniformly occupied both sides of the river, but a little beyond Lidbrook the district of Monmouthshire, called the parish of Welsh Bicknor, extends along the right bank. The boatmen pointed out the north-eastern boundary, which is marked by a hedge, separating a common from a wood, at the extremity of Coppet hill; the common is in Herefordshire, the wood in Monmouthshire.

Here I disembarked, and walked to Courtfield, a seat belonging to the family of Vaughan, which is not unnoticed in the pages of history. . . . [passage omitted]

<P 347> We re-embarked near the church [Welsh Bicknor]; a little beyond

the insulated district of Monmouthshire terminates, and the boatmen pointed

out a fragment of rock lying in the bed of the river, which they called the

county rock, and which marks the junction of the three counties; from this

point the right bank lies in Herefordshire, and the left in Glocestershire.

From the church of Welsh Bicknor, we proceeded without interruption to the

New Weir; during this course, the scenery of the banks assumed a new character;

hitherto it was of a mild and pleasing cast; the  rocks

which formed the rising banks, were so entirely clothed with trees, as to

be seldom visible, or only seen occasionally through the impending foliage;

but in this part of the navigation, the rock became a primary object, and

the stream washed the base of stupendous cliffs. Among these, the most remarkable

are Coldwell Rocks, and Symond's Gate, forming a majestic amphitheatre, appearing,

vanishing, and re-appearing, in different shapes, and with different combinations

of wood and water; at one time starting from the edge of the river, and forming

a perpendicular rampart; at another towering above woods and hills, like the

battlements of an immense castle, as much more sublime than Goodrich, as nature

is superior to art. The weather was peculiarly favourable, the sky clear and

serene, the sun shone in full splendour, illumined the projecting faces of

the rock, and deepened the shade of the impervious woods, which mantle the

opposite banks.

rocks

which formed the rising banks, were so entirely clothed with trees, as to

be seldom visible, or only seen occasionally through the impending foliage;

but in this part of the navigation, the rock became a primary object, and

the stream washed the base of stupendous cliffs. Among these, the most remarkable

are Coldwell Rocks, and Symond's Gate, forming a majestic amphitheatre, appearing,

vanishing, and re-appearing, in different shapes, and with different combinations

of wood and water; at one time starting from the edge of the river, and forming

a perpendicular rampart; at another towering above woods and hills, like the

battlements of an immense castle, as much more sublime than Goodrich, as nature

is superior to art. The weather was peculiarly favourable, the sky clear and

serene, the sun shone in full splendour, illumined the projecting faces of

the rock, and deepened the shade of the impervious woods, which mantle the

opposite banks.

Here the meandring course of the river is peculiarly striking; from the bottom of Symond's Gate to the New Weir, the direct line is not more than 600 yards;* but the distance by water exceeds four miles. At this spot the company usually disembark, mount the summit, and descending on the other side, rejoin the boat at the New Weir. From the top of Symond's Gate, which is not less than 2000 feet in height above the surface of the water,* the spectator enjoys a singular view of the numerous mazes of the Wy, and looks down on the river, watering each side of the narrow and precipitous peninsula on which he stands. I continued the navigation, however, because I was unwilling to lose <P 348> the beauties of the ever shifting scenery, and preferred a succession of home views on the banks beneath, to the most boundless expanse of prospect from above.

In this part the sides of the hills and the bed of the river were strewed with enormous fragments of rock, which almost obstructed the passage of the boat, and rendered the current extremely rapid. For some way the fore ground of the landscape was comparatively tame and dull; but the back ground was still formed by the sublime rocks of Coldwell. At the ferry of Hunston, which is only one mile from Goodrich by land, but seven by water, the rocks disappear, and are succeeded by a ridge of eminences, covered with an intermixture of heath and forest, until we passed the pleasant village of Whitchurch, and reached the New Weir, at which place a sluice is formed for the passage of boats.

The views at the New Weir equal in romantic beauty the scenery at Coldwell rocks; the deep vale in which the river flows, is bounded on one side by the Great Doward, a sloping hill sprinkled with lime kilns and cottages, and overhanging some iron works seated on the margin of the water; on the other rises the chain of precipices forming the side of the peninsula, which is opposite to Coldwell rocks, and vies with them in ruggedness and sublimity. Near the iron works, a weir stretches transversely across the stream, over which the river, above smooth and tranquil, falls in no inconsiderable cataract, and roaring over fragments of rock, is gradually lost in the midst of impending woods.

The remainder of our navigation presented a succession of beautiful scenes, perpetually varied by the undulations of the hills, the richness of the woods, and the abrupt windings of the river, until we reached the bottom of the Little Doward, whose precipitous sides present a rugged rampart of rock. Turning round its southern extremity, we passed under the Lays, a house delightfully situated at the foot of the precipice, overlooking the water, and caught a long reach of the river, terminating in a perspective view of Monmouth bridge, and part of the town, with the spire rising amid tufts of trees.

Monmouthshire here commences on the left bank, with the rich groves of <P 349> Hadnock; on the right, the county is divided from Herefordshire by a small brook, which crosses the turnpike road leading from Monmouth to Ross, and falls into the Wy. We passed on one side a chain of wooded eminences, which stretch from Hadnock to the Kymin, on the other a succession of rich meadows, with the small but sequestered church of Dixon, standing near the margin of the river, and finished the first day's navigation at Monmouth.

<P 350>

Chapter 36.

We embarked on the subsequent morning at nine, below Monmouth bridge, and continued our navigation; the banks on each side are low, and the country level, but bounded at a little distance by ridges of hills; on the right towered the Kymin crowned by the pavilion, on the left we skirted the pleasant meadow of Chippenham, and passed the mouth of the Monmow, which falls tranquilly into the Wy. Behind, we looked back upon a pleasing view of the town, and before the hanging woods of Troy Park formed a delightful object in the landscape, as they rose above the banks of the Trothy, which poured rapidly through a deep and narrow channel, and discoloured with its muddy stream the purer current of the Wy.

About two miles from Monmouth, a small stream called Redbrook separates Monmouthshire from Glocestershire, from which point the Wy continues the boundary of the two counties; here is a small village, where a ferry, and some iron and tin works, give animation to the romantic scenery. Beyond Redbrook the river forms a grand sweep, and flows in an abyss, between two ranges of lofty hills, thickly overspread with woods, the gloom of which was softened by the diversified tints of the autumnal foliage.

In a few places the banks are less steep, expand into gentle undulations, are skirted by narrow meadows, and admit occasional views of the distant country; among which the church and castle of St. Briaval's, crowning the summit of an <P 351> eminence in the forest of Dean, are pleasing objects. We were then hurried along a rapid current, called Big's Weir, where the river eddies over fragments of rock, leaving only a narrow space for the passage of boats. In this picturesque spot the seat of general Rooke, member for the county of Monmouth, stands on the left bank, and on the opposite side Pilson House appears in the back ground. From hence the river winds by the beautiful hamlet of Landogo, situated in a small plain tufted with woods, and backed by an amphitheatre of lofty hills; the view of the church peeping through the trees is extremely picturesque, and is well represented by Mr. Ireland.*

Brook's Weir, a village situated on the left bank, nearly half way between Monmouth and Chepstow, exhibits the appearance of trade and activity. Numerous vessels from 80 to 90 tons were anchored near the shore, waiting for the tide, which usually flows no higher than this place. These vessels principally belong to Bristol, and ascend the river for the purpose of receiving the commodities brought from Hereford and Monmouth, in the barges of the Wy, which on account of the shoals do not draw more than five or six inches of water.

During the course of the navigation from Ross, we passed several small fishing craft, called Truckles or Coricles,* ribbed with laths or basket work, and covered with pitched canvas. Like a canoe, the coricle holds only one person, who navigates it by means of a paddle in one hand, and fishes with the other; these boats are so light, that the fishermen throw them on their shoulders and carry them home.

We disembarked about half a mile above the village of Tintern, and followed

the sinuous course of the Wy. As we advanced to the village, we passed some

picturesque ruins hanging over the edge of

the water, which are supposed to have formed part of the abbot's villa, and

other buildings occupied by the monks; some of these remains are converted

into dwellings and cottages, others are interspersed among the iron founderies

and habitations.

<P 352> The first appearance of the celebrated remains of the abbey church, did not equal my expectations, as they are half concealed by mean buildings, and the triangular shape of the gable ends has a formal appearance.

After passing a miserable row of cottages, and forcing our way through a crowd of importunate beggars, we stopped to examine the rich architecture of the west front; but the door being suddenly opened, the inside perspective of the church called forth an instantaneous burst of admiration, and filled me with delight, such as I scarcely ever before experienced on a similar occasion. The eye passes rapidly along a range of elegant gothic pillars, and glancing under the sublime arches which supported the tower, fixes itself on the splendid relics of the eastern window, the grand termination of the choir.

From the length of the nave, the height of the walls, the aspiring form of the pointed arches, and the size of the east window, which closes the perspective, the first impressions are those of grandeur and sublimity. But as these emotions subside, and we descend from the contemplation of the whole to the examination of the parts, we are no less struck with the regularity of the plan, the lightness of the architecture, and the delicacy of the ornaments; we feel that elegance is its characteristic no less than grandeur, and that the whole is a combination of the beautiful and the sublime.

This church was constructed in the shape of a cathedral, and is an excellent

specimen of gothic architecture in its greatest purity. The roof is fallen

in, and the whole ruin open to the sky, but the shell is entire; all the pillars

are standing, except those which divided the nave from the northern aisle,

and their situation is marked by the remains of the bases. The four lofty

arches which supported the tower, spring high in the air, reduced to narrow

rims of stone, yet still preserving their original form. The arches and pillars

of the choir and transept are complete; the shapes of all the

windows may be still discriminated, and the frame of the west window is in

perfect preservation; the design of the tracery is extremely elegant, and

when decorated with painted glass, must have produced a fine effect. Critics

who censure this window as too broad for its height, do not consider, that

it was intended for a <P 353> particular object, but to harmonize with

the general plan; and had the architect diminished the breadth in proportion

to the height, the grand effect of the perspective would have been considerably

lessened.

The general form of the east window is entire, but the frame is much dilapidated; it occupies the whole breadth of the choir, and is divided into two large and equal compartments,* by a slender shaft not less than fifty feet in height, which has an appearance of singular lightness, and in particular points of view seems suspended in the air.

Nature has added her ornaments to the decorations of art; some of the windows are wholly obscured, others partially shaded with tufts of ivy or edged with lighter foliage; the tendrils creep along the walls, wind round the pillars, wreath the capitals, or hanging down in clusters obscure the space beneath.

Instead

of dilapidated fragments overspread with weeds and choked with brambles, the

floor is covered with a smooth turf, which by keeping the original level of

the church, exhibits the beauty of its proportions, heightens the effect of

the grey stone, gives a relief to the clustered pillars, and affords an easy

access to every part. Ornamented fragments of the roof, remains of cornices

and columns, rich pieces of sculpture, sepulchral stones and mutilated figures*

of monks and heroes, whose ashes repose within these walls, are scattered

on the greensward, and contrast present desolation with former splendor.*

Although the exterior appearance of the ruins is not equal to the inside view, yet in some positions, particularly to the east, they present themselves with considerable effect. While sir Richard Hoare was employed in sketching <P 354> the north western side, I crossed the ferry and walked down the stream about half a mile. From this point the ruins assuming a new character, seem to occupy a gentle eminence and impend over the river, without the intervention of a single cottage to obstruct the view. The grand east window, wholly covered with shrubs and half mantled with ivy, rises like the portal of a majestic edifice embowered in wood. Through this opening and along the vista of the church, the clusters of ivy, which twine round the pillars or hang suspended from the arches, resemble tufts of trees, while the thick mantle of foliage, seen through the tracery of the west window, forms a continuation of the perspective, and appears like an interminable forest.

The abbey of Tintern was founded in 1131, for Cistertian monks, by Walter de Clare, and dedicated to St. Mary. On his death without issue, the patronage was transferred to Gilbert, surnamed Strongbow, who became lord of Striguil or Chepstow, and was created earl of Pembroke. The endowments of the abbey were increased by Gilbert and his successors in the lordship of Chepstow. William of Worcester has preserved the names of the benefactors, among whom was Roger de Bigod, earl of Norfolk, who built the church. He likewise informs us, that in October 1268, the abbot and monks entered the choir of the new church, and celebrated the first mass at the high altar. Probably, however, only part of the edifice was completed, as during this period it was not unusual to construct and consecrate the choir, and afterwards complete the remainder. This opinion is corroborated by the style of the architecture in some parts of the church, particularly in the tracery of the west window, which seems posterior to the æra of the dedication.

At the time of the dissolution the abbey contained thirteen religious, and the estates were valued at £.132. 1s. 4d. per annum, according to Dugdale, but according to Speed, at £.256. 11s. 6d. The site was granted in 28 of Henry VIII. to Henry second earl of Worcester, who possessed the castle of Chepstow, and is <P 355> now the property of the duke of Beaufort. The picturesque appearance of the ruins is considerably heightened by their position in a valley watered by the meandring Wy, and backed by wooded eminences, which rise abruptly from the river, unite a pleasing intermixture of wildness and culture, and temper the gloom of monastic solitude with the beauties of nature.

From Tintern the Wy assumes the character of a tide river; the water is no longer transparent, and except at high tide the banks are covered with slime; to enjoy therefore the full beauty of this part of the navigation, the traveller should seize the moment in which it begins to ebb, when the height and fulness of the river, aided by the picturesque scenery, compensates for the discoloured appearance of the stream.

The impressions of pleasing melancholy, which I received from contemplating the venerable ruins, were increased by the deep solitude and romantic grandeur of the woods and rocks overhanging the river, and heightened by the gloom of a clouded atmosphere.

Hitherto the Wy did not pursue so serpentine a course or present such naked and stupendous cliffs as during yesterday's navigation; but in the vicinity of Piercefield, the sinousities re-appear, and the rocks do not yield in majestic ruggedness to those of Coldwell and the New Weir. The long line of Banagor crags forms a perpendicular rampart on the left bank, wholly bare except where a few shrubs spring from the crevices or fringe their summits; on the opposite side, the river is skirted by narrow slips of rich pasture rising into wooded acclivities, on which towers the Wynd* cliff, a perpendicular mass of rock, overhung with thickets.

At this place the Wy turns abruptly round the fertile peninsula of Lancaut, under the stupendous amphitheatre of Piercefield cliffs, starting from the edge of the water; here wholly mantled with wood, there jutting in bold and fantastic projections,* which appear like enormous buttresses formed by the hand of nature. At the further extremity of this peninsula, the river again turns, and stretches in a long reach, between the white and <P 356> towering cliffs of Lancaut, and the rich acclivities of Piercefield woods. In the midst of these grand and picturesque scenes the embattled turrets of Chepstow castle burst upon our sight; and as we glided under the perpendicular crag, we looked up with astonishment to the massive walls impending over the edge of the precipice, and appearing like a continuation of the rock itself; before stretched the long and picturesque bridge, and the view was closed by a semicircular range of red cliffs, tinted with pendent foliage, which form the left bank of the river.

Notes

Hoare (Editor's note). Sir Richard Colt Hoare (1758-1838) was a historian of the county of Wiltshire in the south of England. He published books on county history and genealogy, including a book on the Hungerford family. He also wrote books on Ireland (1807), Elba (1814), and a report of his travels in Italy, Sicily, and Malta (1819). [back]

* I have simply described this part of the river as it appeared to me; but at particular times, when the river is high, the stream is more rapid, and the cultivated meads in the vicinity, backed by rising hills, appear to advantage. [back]

* (Editor's note.) Copper-plate Perspective Itinerary. The second number ... consisting of ten views of Goodrich Castle. By T. Bonner. London: J. Cary, 1806-07. This is the only edition held by the British Library. Coxe may be citing an earlier edition. [back]

* Determined by Mr. Taylor. Heath's Voyage down the Wye, p. 7. [back]

* (Editor's note). The elevation is actually about 600 feet above the river. [back]

* See Picturesque Views on the Wye, p. 131. [picture] [back]

* The name coricle is supposed to be derived from corium a hide, with which some of these boats were occasionally covered. [back]

* William of Worcester describes it as divided into eight compartments, and ornamented with the arms of Roger de Bigod the founder. Itin. p. 79. The height of the window is 60 feet, and the breadth 27. The height of the east, west, north and south windows, and of the four center arches which supported the tower, from the ground to the point of the arch, is 67 feet. [The Worcester reference is to: The Itinerary of Archbishop Baldwin through Wales A.D. 1188, by Balduinus, successively Bishop of Worcester and Archbishop of Canterbury. A translation by Sir Richard Hoare was published in 1806.] [back]

* Among other sepulchral figures is the mutilated effigies of a man in a coat of mail, with his shield on his left arm, which is erroneously supposed to represent Richard Strongbow, earl of Pembroke, and great nephew of Walter de Clare, the founder of the abbey, who, according to Leland, was buried in the Chapter house of Glocester. According to Grose his right hand has five fingers and a thumb, but the sculpture is so rude, that I could not ascertain whether it has four or five fingers. [back]

* The plan of this church is given on the same plate with that of Lanthony Abbey. See chap. 22. [not provided here] [back]

* Supposed to be a corruption of Wy-cliff. [back]

* Some of these projections are called the twelve Apostles, and another St. Peter's Thumb. [back]

Document prepared August 3rd 2001