Engl 206: The Short Story

Projects, March-April 2004

Photos of some of the groups and the posters of group 7 are included to help remind you who gave each presentation -- although the quality isn't great. Click on a picture to enlarge it.1. Differing representations in modern short fiction

The

project was focused on attempting to define Modernism. In comparison to the

prior period of realism in which the aim was to reveal truth, the Modernist

story shifts to showing the inner life of the individual. This may involve

the "spiral-return" plot, in which a situation is experienced again, now with

greater understanding. The Modernists evolved partly under the influence of

Freud (the conflicted consciousness) and Einstein (relativism in space-time,

time warps). Modernist stories tend to include ambiguity, be focused on apparently

trivial events, and downplay plot. Several stories were discussed in the light

of these ideas (Woolf, Mansfield, Joyce, Hemingway, Faulkner), which provided

a review of Modernist features in more detail, but also with the aim of ascertaining

what is unique or defining about Modernism. Sometimes plot is linear; it may

be temporally disrupted. Sometimes we watch a stream of consciousness; in

other stories no inner life is portrayed. Is there one key feature of Modernism?

The

project was focused on attempting to define Modernism. In comparison to the

prior period of realism in which the aim was to reveal truth, the Modernist

story shifts to showing the inner life of the individual. This may involve

the "spiral-return" plot, in which a situation is experienced again, now with

greater understanding. The Modernists evolved partly under the influence of

Freud (the conflicted consciousness) and Einstein (relativism in space-time,

time warps). Modernist stories tend to include ambiguity, be focused on apparently

trivial events, and downplay plot. Several stories were discussed in the light

of these ideas (Woolf, Mansfield, Joyce, Hemingway, Faulkner), which provided

a review of Modernist features in more detail, but also with the aim of ascertaining

what is unique or defining about Modernism. Sometimes plot is linear; it may

be temporally disrupted. Sometimes we watch a stream of consciousness; in

other stories no inner life is portrayed. Is there one key feature of Modernism?

This project was certainly useful as a way of reflecting on the features of Modernism, providing helpful suggestions for revising the topic. It also provided several suggestions for how to read a number of stories for their Modernist features. It didn't begin to question the features themselves. If truth was the aim of realism, what is the aim of Modernism? How effectively do Freud's ideas about our conflicted mental life map on to Modernist thinking? (Freud was disputed in England most prominently by D. H. Lawrence). Don't literary works from other periods also often focus on apparently trivial events (Pope's "Rape of the Lock," Coleridge's "The Mariner"): the Modernists are not the first to engage in symbolism that promotes the significance of the insignificant. The beginning of an answer might lie in the representation of consciousness as unreliable, as (in part) constructing the reality it supposes itself to represent. But perhaps the most important feature is to promote the inner life as the stage on which the real dramas are played out (whether explicitly portrayed, as in Woolf, or left to the reader to infer, as in Hemingway).

2. Style transcends gender

Taking

the concept of "écriture féminine" of Hélène Cixous, the group considered

the question whether such a style exists and can be distinguished in the short

story. Apart from the possibility of reinscribing patriarchy through such

a concept, it was argued that the stylistic qualities that distinguish the

short story are in the competence of both male and female writers. Four areas

were proposed as fields for the claims of style over gender. 1) Three kinds

of poetic language were analysed with examples from Faulker and Mansfield:

the embodying of experience in sentence structure, the power of imagery, and

figurative language. 2) Minimalism, the ability to convey much through a minimum

of detail and simple dialogue (Hemingway and Hempel as examples). 3) The literary

twist, in which stories work up to a surprising denouement: Poe telling us

his story 50 years later, and O'Connor's Hulga, when "her crutch of embittered

atheism was stolen from her." And 4), the epiphany (as exhibited in Joyce

and Woolf). The group conclude that style provides a higher ground than gender

from which to estimate the skills of the short story, and that we cannot infer

gender from style.

Taking

the concept of "écriture féminine" of Hélène Cixous, the group considered

the question whether such a style exists and can be distinguished in the short

story. Apart from the possibility of reinscribing patriarchy through such

a concept, it was argued that the stylistic qualities that distinguish the

short story are in the competence of both male and female writers. Four areas

were proposed as fields for the claims of style over gender. 1) Three kinds

of poetic language were analysed with examples from Faulker and Mansfield:

the embodying of experience in sentence structure, the power of imagery, and

figurative language. 2) Minimalism, the ability to convey much through a minimum

of detail and simple dialogue (Hemingway and Hempel as examples). 3) The literary

twist, in which stories work up to a surprising denouement: Poe telling us

his story 50 years later, and O'Connor's Hulga, when "her crutch of embittered

atheism was stolen from her." And 4), the epiphany (as exhibited in Joyce

and Woolf). The group conclude that style provides a higher ground than gender

from which to estimate the skills of the short story, and that we cannot infer

gender from style.

The departure point is a bold one, and led the group to provide a complex scheme for understanding and discussing style in the short story, one that at the same time provided a useful overview of what may be distinctive about the short story (as well as inpenetrable to gender scrutiny). The concept of gendered style goes back, of course, to Woolf, whose complaint about a male-dominated language might provide another point for discussion. Cixous herself suggests that "écriture féminine" is not strictly identified with the gender of a writer:she cites Joyce and Genet as examples of writers who demonstrate it. Rather, for her it is in particular a question of gender politics: as she says, "it will always surpass the discourse that regulates the phallocentric system: it does and will take place in areas other than those subordinated to philosophical-theoretical domination." She has in mind a writing of openness, of excess, beyond male reason and order. Could any of the short stories we've studied be considered in this light?

3. Character in a Short Story: What's the Difference?

The

main argument was that character is different in the short story. The writer

must be highly selective given the constraints of space, so physical development

is often excluded. The use of an easily recognized stereotype is economical

way of engaging the reader's immediate understanding and knowledge, e.g.,

the "dull young man" in O'Connor. Yet in the short story the focus is on the

dynamic aspects of character, whether the elaboration of consciousness in

the Modernist story, or social interaction in the Post-Modern; but in each

case this is undetermined by the past, it is confined to the moment, the "flash."

Women said to figure little in stories until the 1950s onwards (Conrad and

Chekhov are compared with Laurence, Munro). The story tends to focus on a

moment of truth, which, it is argued, may often depend on the author's own

experience, as proposed in the case on gender. "Characters are like windows

that let us see an ultimate truth about humanity."

The

main argument was that character is different in the short story. The writer

must be highly selective given the constraints of space, so physical development

is often excluded. The use of an easily recognized stereotype is economical

way of engaging the reader's immediate understanding and knowledge, e.g.,

the "dull young man" in O'Connor. Yet in the short story the focus is on the

dynamic aspects of character, whether the elaboration of consciousness in

the Modernist story, or social interaction in the Post-Modern; but in each

case this is undetermined by the past, it is confined to the moment, the "flash."

Women said to figure little in stories until the 1950s onwards (Conrad and

Chekhov are compared with Laurence, Munro). The story tends to focus on a

moment of truth, which, it is argued, may often depend on the author's own

experience, as proposed in the case on gender. "Characters are like windows

that let us see an ultimate truth about humanity."

The main problem with the approach here is that Modernist stories are largely excluded from consideration. Such an account would have qualified several of the claims made, in particular: 1) the dependence on stereotypes is probably not apparent until after the Modernist period (think of the individualized characters, and their inner lives, in Mansfield, Woolf, Lawrence). And 2), the comment about women overlooks the significant focus on women's experience in those same Modernist authors (Vera in "A Dill Pickle," Julia Craye in "Slater's Pins," and Mabel in "The Horse Dealer's Daughter"), where several of the leading authors are themselves women. The commentary on stereotypes seems apt within their limits, but I would suggest that recourse to the stereotype also signals a loss of confidence in the reality of the rich inner life and its individuality, a sense that people are determined largely by the roles they play. The other comments on character and how it is limited in scope in the short story are helpful; they tend not to go beyond their sources (in Geddes or the authors he excerpts).

4. Conflict in the Short Story

The

project presented accounts of three stories designed to examine the thesis

that "The conflict in a short story is driven by cultural views of morality."

About two thirds of the time was given to a discussion of Akutagawa (his biography

and the Japanese background) and his story "In a Grove," which raised questions

about the honour culture that appears to dictate the characters' testimonies

and the conflicts in what they say. Briefer comments were made on "Heart of

Darkness" (the conflict between the noble aspirations and the immoral outcome,

especially focused in Kurtz), and "The Shining Houses" (the conflict of moral

obligations felt by Mary both towards Mrs. Fullerton and towards her own community);

and a suggestion that concepts of honour and dishonour are culturally specific,

thus a short story must be understood within its own culture.

The

project presented accounts of three stories designed to examine the thesis

that "The conflict in a short story is driven by cultural views of morality."

About two thirds of the time was given to a discussion of Akutagawa (his biography

and the Japanese background) and his story "In a Grove," which raised questions

about the honour culture that appears to dictate the characters' testimonies

and the conflicts in what they say. Briefer comments were made on "Heart of

Darkness" (the conflict between the noble aspirations and the immoral outcome,

especially focused in Kurtz), and "The Shining Houses" (the conflict of moral

obligations felt by Mary both towards Mrs. Fullerton and towards her own community);

and a suggestion that concepts of honour and dishonour are culturally specific,

thus a short story must be understood within its own culture.

The concept here was a promising and original one, and could provide an interesting perspective on a number of stories in which moral conflicts are central (from Chekhov to King). The difficulty we were set in the way of understanding lay in 1) failing to provide an introduction to the thesis underlying the presentation (this was not stated clearly until near the end), and 2) spending too long elaborating the background of Akutagawa and describing his story; here the historical details tended to obscure rather than illuminate the points about the honour code implicated in the story (I'm still unsure about the relevance of the 47 Ronin). The final question, Is moral conflict central to the short story, was well worth asking, and elicited some comments. The larger issue of how cultures represent morality might have been considered as well, since the Munro story ("put your hands in your pockets"), and perhaps some other recent stories, raise the question whether a generally agreed moral framework is possible any longer.

5. Cultural assimilation in "Borders," "The Loons"

The primary focus in this presentation was on the loss of native culture, as demonstrated in the two stories chosen. This was shown in both stories as a token acknowledgement of native culture at just the point that it has become irrecoverable: Piquette is dead, the narrator in "Borders" fails to listen to his mother's stories. The discussion was organized by pointing to pairings between characters in the two stories (Vanessa and the child narrator, Piquette and Laetitia, etc.), which helped to foreground several useful points about the endangerment of native culture. Separate discussions were also offered of the biography of both authors, and the inability of Western culture in general to engage seriously with the native in its midst. Some history of dealings with natives in Canada was also briefly presented.

The effect of the presentation was to offer quite detailed readings of both stories, which made both reveal poignant subthemes of native dislocation and loss. It also pointed to the implications of having participant narrators who were unreliable, both being children (at least at first, in "The Loons"). The overall approach was well organized and provided an occasion for some detailed critical work. As with other projects that focused on a quite specific topic, it left unanswered questions about the applicability of the ideas beyond the two stories chosen. Were the correspondences fortuitous, or is there a larger conclusion that can be drawn? Can we look at other examples of cultural conflict where a way of life is being extinguished ("The Shining Houses"), or even examples where one life is in jeopardy ("Hills Like White Elephants"); and, if so, are there underlying aesthetic principles at stake, such as those we are familiar with in the case of tragedy?

6. Authors' background influence on their stories

In this project the presenters set out to show that the biographical background of authors is a detectable influence on their fiction. Two authors were chosen. Some time was given to considering Poe's life, where his gambling and drinking were seen as reflected in his characters Montresor and Fortunato, while we see Poe's pride in his family reappearing as a trait of Montresor. Poe's interest in Gothicism led to an account of Gothic features, some of which mapped effectively onto "The Cask of Amontillado," including the problem of how we are to relate to a first person narrator who is psychopathic. Less time was left for O'Connor, whose isolated character was associated with that of Hulga, while her "Christian skepticism" provided a context for the story (its lack of an evident moral frame).

A number of the individual points were well made. Overall, however, it wasn't clear what the status of the claims were. In some respects it seems obvious that a writer's background must influence the writing, but the examples we were given were specific to the two writers, and seemed too idiosyncratic to generalize to other writers, although more could perhaps have been done with the Gothic criteria. Nor are such claims specific to the short story, of course: it is a point we could make (and invariably has been) about any writer of interest we examine. It also raised such questions as: 1) how far experience is transmuted in the writing, i.e., set at a distance from the original experience; 2) what principles might govern such an analysis, given the recourse not only to actual experience but to the supposed phenomena of psychoanalytic inquiry.

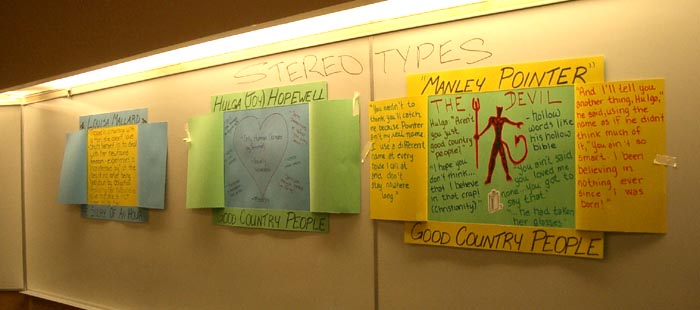

7. Stereotypes in the short story

The

group presented an argument about the dramatic nature of several stories,

in that these present us with a readily identifiable stereotype of a character,

then surprise us by revealing a quite different character. This argument was

applied to Mrs Mallard in "The Story of an Hour," whose conventional status

as a grieving wife hardly prepares us for the "monstrous joy" she comes to

feel; and to "Good Country People," where both Hulga and Manley Pointer are

revealed as something quite different by the end: Hulga, in losing her

The

group presented an argument about the dramatic nature of several stories,

in that these present us with a readily identifiable stereotype of a character,

then surprise us by revealing a quite different character. This argument was

applied to Mrs Mallard in "The Story of an Hour," whose conventional status

as a grieving wife hardly prepares us for the "monstrous joy" she comes to

feel; and to "Good Country People," where both Hulga and Manley Pointer are

revealed as something quite different by the end: Hulga, in losing her  glasses

and her wooden leg, is shown as helpless, a blind atheist; Pointer, by getting

himself invited into the lives of the other characters, gains power over Hulga,

and is revealed as a nihilist, if not The Devil himself. The presentation

made clever use of three posters, each with windows showing first the stereotyped

character, then, when folded back, the character as revealed.

glasses

and her wooden leg, is shown as helpless, a blind atheist; Pointer, by getting

himself invited into the lives of the other characters, gains power over Hulga,

and is revealed as a nihilist, if not The Devil himself. The presentation

made clever use of three posters, each with windows showing first the stereotyped

character, then, when folded back, the character as revealed.

The argument was quite convincing within its limits. It suggested how the short story can be enlivened in particular by such a plot denoument (cf. the "literary twist" described in Project 2), but by limiting the analysis to two stories it left open the question how far the insights could be generalized. Could it apply to other stories where the "true" character is revealed? ("The Horse Dealer's Daughter" for example?). And, given the limited space allowed for the short story, does it also point to a more general technique by which authors are able to call up a reader's schema of a character type in order to establish character quickly and economically? (e.g., Vanessa the child in "The Loons"). And would such a technique be less available to a postmodern writer, for whom there is nothing behind the stereotype?

8. Postmodernism in short stories contrasted with modernism

The

group focused on characterizing modernist vs. postmodernist stories, while

arguing that there is no clear dividing line; instead, we were shown a continuum

with four stories on it, from Lawrence at one end to Gallant at the other.

It was argued that modernism is an heir of the Enlightenment, with a commitment

to permanent truth, even though it may be necessary to penetrate the surface

of appearances to locate it. In postmodernism, in contrast, such truths are

no longer credible, representations are all we have (Lyotard, Foucault, Baudrillard

cited in support). In terms of techniques, modernism was shown to depend on

limited omniscient narrators, postmodern on first person, which signals the

shift towards relativism and the greater interpretive freedom of the reader.

Several stories were discussed in some detail, e.g., "The Loons," in which

the end (the disappearance of the loons) was seen as signalling the death

of modernism. Some lively discussion followed about which kind of text readers

in the class preferred.

The

group focused on characterizing modernist vs. postmodernist stories, while

arguing that there is no clear dividing line; instead, we were shown a continuum

with four stories on it, from Lawrence at one end to Gallant at the other.

It was argued that modernism is an heir of the Enlightenment, with a commitment

to permanent truth, even though it may be necessary to penetrate the surface

of appearances to locate it. In postmodernism, in contrast, such truths are

no longer credible, representations are all we have (Lyotard, Foucault, Baudrillard

cited in support). In terms of techniques, modernism was shown to depend on

limited omniscient narrators, postmodern on first person, which signals the

shift towards relativism and the greater interpretive freedom of the reader.

Several stories were discussed in some detail, e.g., "The Loons," in which

the end (the disappearance of the loons) was seen as signalling the death

of modernism. Some lively discussion followed about which kind of text readers

in the class preferred.

The distinctions made were plausible, and provided a useful framework for analysing technical differences in the stories, such as contrasting types of narrators and the occurrence of free indirect discourse. The emergence of Modernism probably has much to do with a new insight into the unreliability of consciousness, hence the detailed inquiries into feeling, memory, etc., of Woolf, Mansfield; behind these lie such figures as the French symbolist poets, Freud, and the post-impressionist painters, which places modernism at some distance from Enlightenment beliefs, although in the epiphany we have a residual sense that truth may yet be attainable. The significant use of stereotypes in a story such as "The Loons" (e.g., the young Vanessa's conception of natives) is perhaps more equivocal than was suggested, since it signals the reality of Piquette's condition even though this cannot be seen by Vanessa at the time; i.e., Piquette is more than the set of stereotypes imposed on her. In a full-blown postmodern story this would not be apparent. Despite some mis-timing ("The Loons" took up too much time), the presentation was thoughtful and provocative.