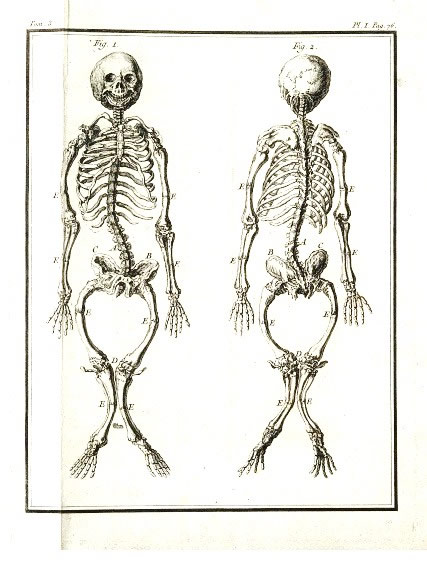

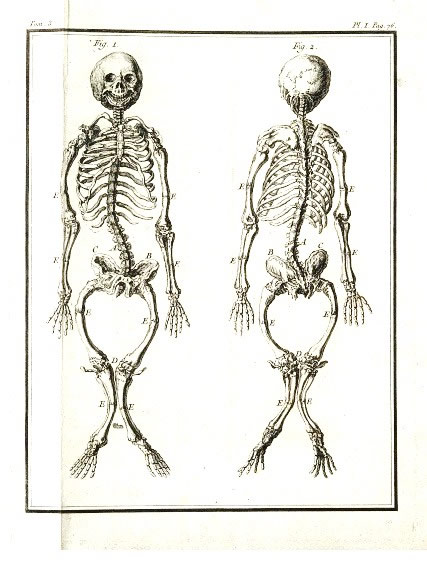

Engraving from Histoire naturelle, 1749, Courtesy of the Wellcome Library

Early Modern Illnesses and Treatments

Surgeries, Deformities and Disease

Rickets

by Emily Dymock

|

| Skeleton of a Ricketic Child Engraving from Histoire naturelle, 1749, Courtesy of the Wellcome Library |

“A disease very ordinary at this time amongst children, which they call the rickets, wherein the nourishment goeth all to the upper parts, which are over great and monstrous, and the lower parts pine away.

This description was taken from a parliamentary address given in England in 1640, which addressed the rampant spread of rickets throughout England, affecting mainly children in urban centres. According to the early modern physician who wrote A Sick-Mans Rare Jewel in 1674, (recorded only by the initials B.A.) rickets was primarily caused by an overwhelmingly cold and moist distemper that affected the bone marrow throughout the spine and travelled into the brain.(2) Early modern physicians argued that a lack of nutritional food aggravated an existing cold temperament in the child’s body, which led to the manifestation of the disease. However, today’s medical practitioners contend that rickets is primarily caused by a vitamin D deficiency which causes calcium to leak out of the bones. A leader in early modern children’s medicine, Michael Underwood, who worked in late eighteenth century England, and who published a treatise in 1784 on children’s illnesses, estimated that rickets did not appear in England until 1628, which he argued coincided with migration of many rural farmers into larger urban cities.(3) Rickets impacted children throughout the majority of European cities, but as it was especially common in England it earned the nick-name the ‘Englishman’s disease’.

The most widely read early modern medical treatise devoted to the causes, symptoms and treatment of rickets was written by Francis Gilsson in 1650. Gilsson (1597-1677) was an English physician who was born in the village of Rampisham in Dorset. His treatise was not the first to deal with the subject of rickets, but it was the most popular.(4) He doubted that the cause of rickets could be explained by a simple lack of nutritional foods. In his text he argued that the illness was first communicated to the child while inside its mother’s womb. He argued that:

“first, there hapneth a cold and moist distemper of the womb itself, which (as were we silent is easily manifest in everyone) may most readily be communicated to the embryon by th perpetual contact of the womb”(5)

Gilsson continued that if the seeds (the reproductive fluids produced by men and women alike) and the womb which created and nurtured the embryo were troubled by a cold and wet distemper then the child would have a greater susceptibility of contracting the condition. A person’s temperament, in this case the mother’s, was affected by her diet, excessive physical labour or sleep, bleedings, fevers, or by nursing another child while pregnant with another, and early modern practitioners argued that these activities would impact the nutrients being passed to the embryo, affecting its humoural balance.

After children were born, rickets typically did not manifest until the child was at least six months old. In the youngest years of life, Gilsson argued that the manifestation of rickets was influenced and aggravated by five external factors, the first of which was air. Children with an existing distemper in their bone marrow could have their condition exacerbated by spending time outside surrounded by excessively cold and moist air. The second external factor was eating meats that were not well prepared and could aggravate an existing predisposition in to a fully formed, and potentially severe case of rickets. Motion and exercise were the third on the list, and Gilsson argued that young children should not be allowed to take too much exercise, which caused them to sweat and become vulnerable cold. At the same time, he cautioned that too little physical activity would slow the flow of blood, rendering a child’s body cold and sluggish. The same effect would be created if a child slept excessively. The final external cause involved draining fluids from the body in order to maintain humoural balance, by means of purgings, bleeding or diaretics, all standard medical practices during the early modern period. Gilsson urged caution when performing these procedures on children and recommended cutting the vein behind the ear, which allowed blood to flow out of the head, where it had accumulated in order to return the body to a state of balance.(6)

|

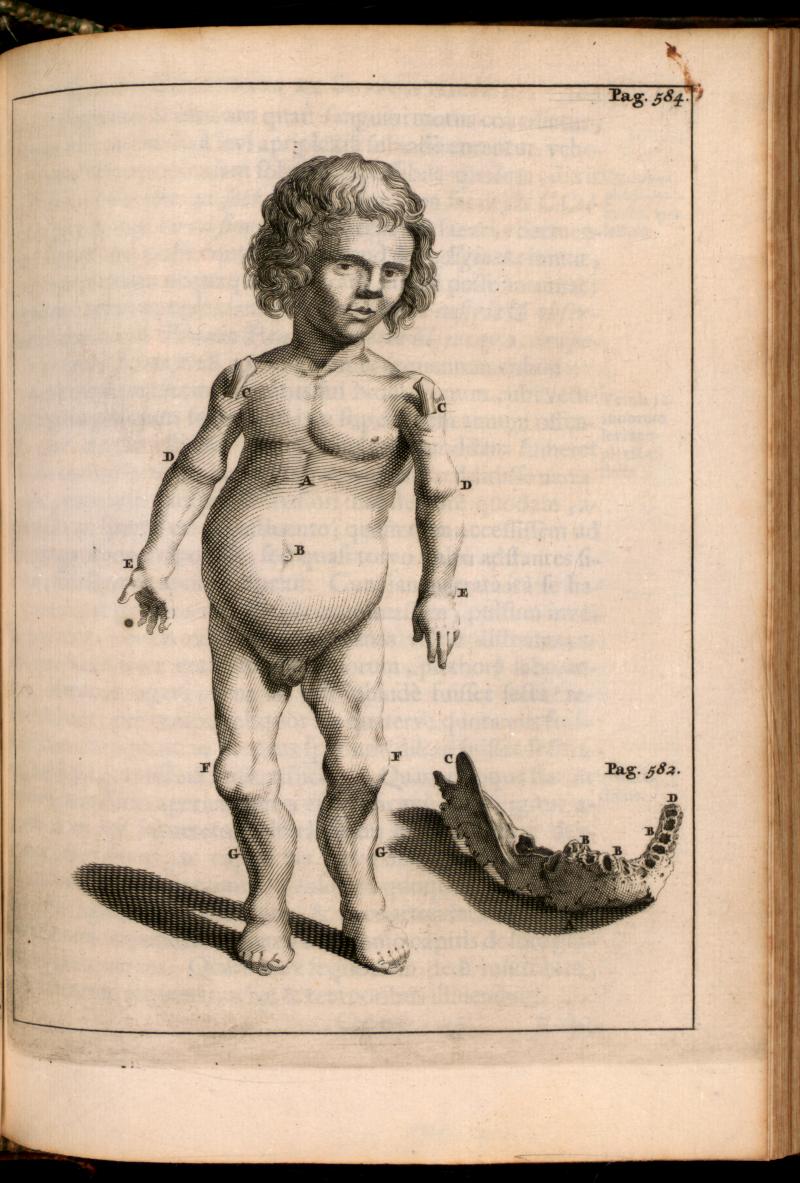

| Patient with Rickets Engraving taken from Exercitationes Practicae, by Frederick Dekkers, 1644-1720 |

A later physician, also from England, John Pechey, who published A General Treatise of the Diseases of Infants and Children (1697), argued that the first symptoms of rickets which appeared at the onset of the condition were a persistent fever, prickling pain in the joints, and difficulty breathing. As the disease progressed, Pechey observed that the limbs became thin and wasted, the skin hung loosely off the skeleton, and the bones and joints eventually became so weak that they could no longer support the weight of the body. As a consequence of this deteriorating weakness, the larger bones in the body, the legs and arms, began to bend. Pechy argued that by the time that children with rickets were six months old their heads and faces seemed to be much larger than the rest of the body. These deformities can be seen in an engraving made by Joseph Mulder for a medical treatise entitled Exercitationes Practicae, published in 1695. This young boy has the bowed limbs and small stature associated with a child who had long suffered from rickets. His shoulders joints protrude from his skin, drawing attention to unnaturally large and swollen joints associated with this disease. The detail to the right of the child shows the deterioration of the teeth, and the porous remains of a jaw bone. One symptom that Pechey listed in his description of rickets that is not shown on this young boy was known as pigeon breast, where the child’s breast bone rose to a point, like that of a bird, rather than sitting flat. This he considered characteristic of the most severe cases of rickets. He observed that children who suffered at length from rickets could become invalids, stunted in size for their entire lives, which made them easily mistaken for dwarves.(7)

Gilsson believed that the cure for rickets was to expel whatever corrupting humours that had caused the disease. However, he warned that the treatments could not be as strong as the purges used to cure sick adults as sick children did not have the strength to withstand them. Gilsson posited that the best way to expel the damaging humours was to use a purge that had the opposite essence of the disease. As rickets’ essence was cold and moist, the best solution would be rhubarb because its essence was considered to be hot and dry, and it was not too powerful for children to withstand. Gilsson argued that rhubarb would strengthen the weakness in the joints and the internal organs, while correcting the cold that had settled into the bone marrow.(8)

During the same time period in which Gilsson’s work was published, a physician working in the court of Queen Elizabeth (known only as A.M.) published an extensive medical treatise on the most common diseases in England. He claimed to have collected and recorded these diseases and cures found in medieval manuscripts, as well as from the experiments and observations recorded by other court physicians. A recommended cure for rickets was to:

“Take of cream two pounds, and boil it to an oyle or take of unfalted butter, take three or four good handfuls of Cammomil, mince it small and put it into hearbes become crispe and that it be very bitter; then strein it and anoint the childs sides dosnwards, and the bottome of the belly and the thighs morning and evening: Also give the child thrice a day half a dozen spoonfuls of harts-tongue water, in which you have steped seven or eight cloves and some brown sugar candie to sweeten it.”(9)

After pharmaceutical remedies had been used to correct the humoural imbalance, many early modern physician, including Underwood, Gilsson and the physicians of Queen Elizabeth’s court recommended that children should be reintroduced to fresh air and exercise, albeit in moderation and with constant supervision.

|

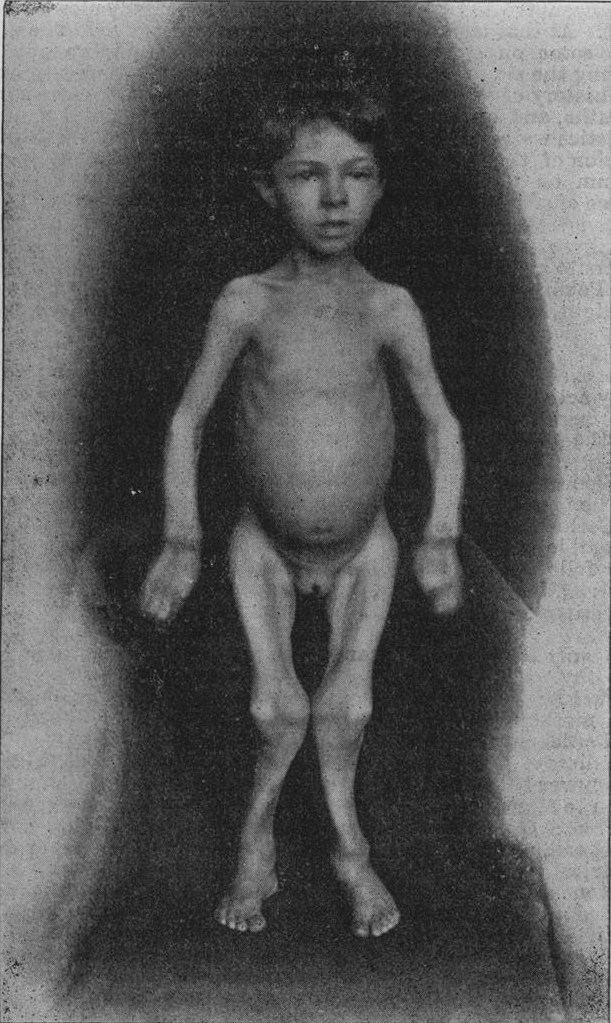

| Late onset Rickets Taken from Edmund Cautley. “Recrudescent or Late Rickets.” The British Medical Journal, Vol 1, No. 1827. Jan 2. 1896. BMY publishing Group. p. 13 |

The frequency of rickets continued to increase during the nineteenth century. Autopsies performed in late nineteenth-century Boston and Leiden showed that 80 to 90% of children suffered from rickets.(13) Rickets also began to develop in older children, especially in those ranging in age from 9 to 14. The late onset of rickets entailed the same symptoms listed above as well as a delayed onset of puberty.(14) In 1822 Jedrzej Sniadecki (1768-1838), a prominent polish physician and chemist, was one of many physicians at the time who discovered the therapeutic value of exposing children with rickets to the suns UV radiation, which increased their intake of vitamin D.(15) However, vitamin D would not be discovered as a unique compound until after the World War One by Edward Mellanby (1884-1955). He was a British physician, and a professor of pharmacology at the University of Sheffield, and he discovered that cod liver oil was an excellent source of vitamin D, which made it extremely effective in preventing rickets; it had in fact been used since the eighteenth century as a folk remedy in northern countries. Mellanby discovered that vitamin D could be absorbed through certain foods, or through the skin when exposed to UV radiation.(16) According to him, when the body did not have enough vitamin D, the calcium and phosphate was leached out of the bones, causing the weakness and the bending of the bones.

After Mellanby’s research it became a much more common practice to give children cod liver oil to supplement their vitamin D intake, especially countries in the northern hemisphere which lack natural sunlight during the winter, and the rates of rickets amongst children dropped dramatically. However, The Sunday Times, on January 22, 2010 reported a resurgence of rickets, approximately twenty new cases a year, amongst British youth in the last few years. Many scientists cited in the article blamed the amount of time that children spend in front of the computer screen or the television, as well as the disappearance of practice of administering cod liver oil. Doctors, including Professor Simon Pearce and Tim Cheetham of New Castle University are currently petitioning for the supplementation of such foods as milk with vitamin D (a common Canadian practice) which would increase the public intake of this important vitamin.(17)

Notes:

1)News. Speeches and Passages of This Great and Happy Parliament. (London, England), Tuesday, November 3, 1640. Sourced from the British Library. 17th-18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers.

2)B.A. The Sick-Mans Rare Jewel. (London: Printed by T.R and N.T., 1674)p 189.

3)Michael Underwood, A treatise on the Diseases of children with directions for the management of Infants from the Birth. (London: J Mathews, 1784.) p119.

4)Denis Gibbs, “Rickets and the Crippled Child: an historical Perspective” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Volume 87, December 1994, p729.

5)Francis Gilsson, George Bate, and Ahasuerus Regemorter. A Treatise of the Rickets Being a Disease common to Children. (London: Peter Cole, 1651) p 161.

6)Ibid, p 166-175.

7)John Pechey. A General Treatise of the Disease of Infants and Children. (London: Printed for R. Wellington, 1697) p148.

8)Francis Gilsson, George Bate, and Ahasuerus Regemorter. A Treatise of the Rickets Being a Disease common to Children. (London: Peter Cole, 1651) p336.

>9)M.A. Queen Elizabeth’s Closset of Physical Secrets. (London: Will Sheares, 1656) p 63.

10)Michael Underwood, A treatise on the Diseases of children with directions for the management of Infants from the Birth. (London: J Mathews, 1784) p121-122.

11)Neil K. Kaneshiro, MD, MHA and David Zieve, MD, MHA. “Rickets” Medline Plus. August I, 2008. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000344.htm.

12)John Pechey. A General Treatise of the Disease of Infants and Children. (London: Printed for R. Wellington, 1697) p 148.

13)Michael F. Holick. “Resurrection of Vitamin D deficiency and Rickets.” Journal of Clinical Investigation. Volume 116, Number 8, August 2006. P 2062.

14)Edmund Cautley. “Recrudescent or Late Rickets.” The British Medical Journal, Vol 1, No. 1827. Jan 2. 1896. BMY publishing Group. p. 13

15)Michael F. Holick. “Resurrection of Vitamin D deficiency and Rickets.” Journal of Clinical Investigation. Volume 116, Number 8, August 2006, p 2062.

16)Ibid, p 2062.

17)David Rose, “TV and computer games blamed for the return of rickets” The Sunday Times Online. January 22, 2010.