Engraved by Cornelis Huybert. From Opera Omnia Anatomico-medico-churgica. By Frederik Ruysch. 1638-1731

Early Modern Illnesses and Treatments

Surgeries, Deformities and Disease

|

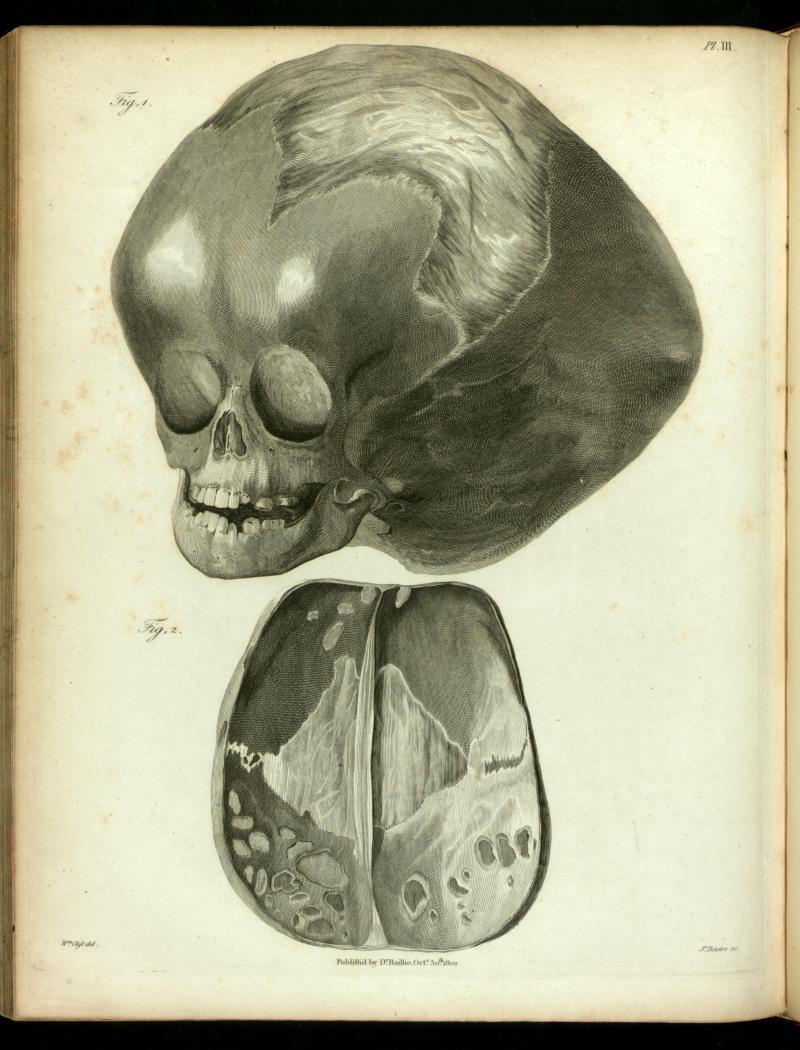

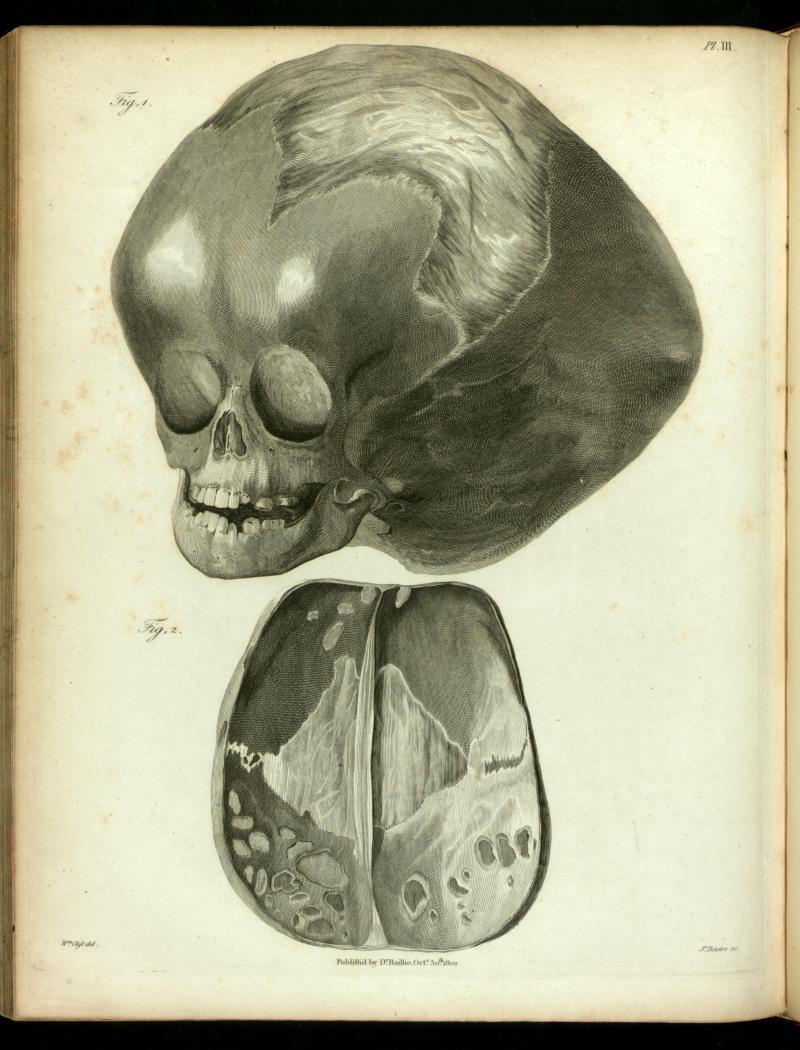

| Infant with Hydrocephalus

Engraved by Cornelis Huybert. From Opera Omnia Anatomico-medico-churgica. By Frederik Ruysch. 1638-1731 |

“Early modern medical practitioners argued that hydrocephalus was a rare condition that resulted in the collection of watery humours in the heads of newborn infants and young children."

Today, modern physicians and medical practitioners argue that hydrocephalus is caused by an excess of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) within the ventricles of the brain. In contrast, early modern physicians insisted that this rare flooding of the brain with watery humours occurred when a child’s bodily constitution was weakened by an inadequate diet that included too much raw whey and fruit.(1) According to Isbrand de Diemerbroeck, a leading physician in the Republic of the Seven United Provinces (now the Netherlands) at the end of the seventeenth century, these foods caused the over production of phlegmatic or sluggish humours that travelled from the bowels to the head in the form of thick vapours, gathering until they were too copious for the body, and ultimately causing the heads of young children, whose skull plates remained unfused, to swell dangerously.

Many early modern treatises were written to be used by medical practitioners as well as nursemaids and parents in their homes. Nicholas Culpeper, an English physician and herbalist who worked around the same time as Diemerbroeck, and who wrote, among other things, a Directory for Midwives or, A Guide for Women (1662), argued that hydrocephalus was caused by too much moisture within the brain which had either gathered near the skull or in the ventricles of the brain. Culpeper’s treatise recommended several home remedies that could be applied to the ears and nose which counteracted the collection of moisture in the brain. He recommended taking:

"snails in their shells thirty, Majoram, Mugwart, each a handful; stamp, add Camphire a scruple, Saffron half a dram, with oyl of Chamomil make a pultis. Snuff this water often. (2)"

However, Culpeper also warned that this disease was extremely difficult to cure, and that most children who were afflicted with it would die. Another treatise written by Robert Bayfield in 1663 recommended that an ointment made from oil of chamomile and brimstone powder be applied twice daily, noting that wrapping the child’s head, warm dry wool could reduce the swelling.(3) Within early modern medicine, and the humoural understanding of the body, the cure to any particular ailment would be to introduce the opposite temperament to the illness. The temperament of Bayfield’s treatment is warm and dry (especially the brimstone powder), which counteracts the cold moist humours that had afflicted the child’s brain.

|

First Page of Le Cat's Treatise |

The early modern treatises mentioned above stressed that the first course of treatment should consist of at least twenty days of pharmaceutical remedies before any surgery was attempted, as surgery would be as likely to kill the ill person as to cure them.(4) Today, medical professionals argue that the sooner a child with hydrocephalus can receive surgical aid, the better his or her chances of survival. Despite the pronounced hesitation to pursue aggressive interventions during the early modern period, there were surgical treatments for hydrocephalus. One method of surgery that was invented then is described in a treatise entitled A New Trocart for the Puncture in the Hydrocephalus and for other Evacuations, which are necessary to be made at different times, written by the French physician M. Le Cat, translated into English by Theodore Stack, and published in 1752. This treatise recognised the danger of operating on the brains of small children. However, Le Cat argued that the reason the majority of children died from surgery was because the fluid was drained too quickly after the surgeon had punctured their skull, putting the child’s body into a state of shock. Le Cat invented a new trocar that could be used to drain more slowly the excess fluid from the brains of children afflicted with hydrocephalus. Le Cat explained his treatment by recounting the case of Peter Michel, a three-month old infant whose head had swelled to an enormous size in a mere five weeks. Le Cat had hesitated before treating Peter because the child’s case of hydrocephalus was severe and the French physician argued that regardless of the treatment, young Peter would likely not survive. Yet when the child’s parents persisted, le Cat decided to apply his newly invented tool, which he hoped would drain the fluid at a moderate rate. Le Cat intended to drain small amounts of fluid every two days in an attempt to slowly reduce the swelling and cure the young boy.(5) The physician recounted his procedure:

|

| Infant with Hydrocephalus Engraved by Cornelis Huyberts, taken from Frederik Ruysch's Theraurus Anatomicus, 1701. Courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto |

"I performed the puncture on Friday the 23 of October 1744, by thrusting in the trocart and canula up to the circles and plaster, which I applied and made to stick in all its parts on the head, by pressing it with my hand and fingers made very warm and also with hot linen cloths. When the plaster was thoroughly well fastened on, I pulled out the trocart and drew for or five ounces of serosity, of a brownish white, or the colour of pail white-wine, and somewhat foul; after which I closed the canula with its stopple.(6)"

This procedure was repeated twice again, but the young boy could not take the strain on his body and he died the night after his third treatment. Le Cat performed an autopsy, and confirmed that Peter was indeed incurable, as the brain had been under so much pressure that it was much thinner than a healthy child’s brain because it had been pressed against his skull by the excessive pressure created by the build up of fluid.(7)

Another autopsy done on a two-year-old boy who had died of hydrocephalus was recorded by John Friend in a letter to the leading English physician Doctor Hans Sloane. Friend related the damage done to the boy’s brain and the skull by the accumulation of watery humours. He recorded that none of the bone plates in the skull were fused together: instead they were connected by cartilage membranes (like those in the etching) because the brain had accumulated so much liquid, that the skull had never had the opportunity to fuse after the child’s birth. When Friend pierced the dura matter approximately five quarts of liquid (4.5L) that had collected between the dura and the pia matter flowed out. The pia matter itself was stretched and lay smoothly across the surface of the skull, rather than following the bumps and curves of the brain as it should, and several of the internal structures of his brain were smaller than they should be in a boy of his age.(8) Friend related to Dr. Sloan that the young boy was unable to hold up his own head and had extremely poor sight. But despite his illness he maintained a good mood and, according to Friend, he did not suffer from any of the headaches or the severe drowsiness associated with this condition- until the last few days of his life.(9)

|

| Diseased Brain Taken from Joseph Vimont’s Traite de Phrenology humaine et compare. (Paris: J.B. Bailliere, 1832-35.) Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine |

Michael Underwood, a leader in children’s medicine in England, who worked in a lying-in hospital in the late eighteenth century, detailed several other symptoms that affected children with hydrocephalus. He argued that the disease would start with a slow fever, pain in the forehead and vomiting. The head would eventually become heavy, the pulse irregular and slow, and the child developed a strong sensitivity to light. In the last stages of the disease the children would become delirious and began to see double. In the most advanced cases the child’s pulse would race, their pupils would be extremely dilated, and the child would slip into a comatose state. In the moments before death, Underwood recounts that the majority of children with hydrocephalus suffered from strong convulsions. He argued that it was extremely difficult to diagnose, let alone cure hydrocephalus because the disease could never be truly diagnosed without an autopsy, and therefore, if a child survived it could very well have meant that they had simply not been afflicted with hydrocephalus to begin with.(10) When imaging hydrocephalus many early modern medical texts show the child’s swollen skull, focusing on the strain that collecting humours have placed on the connecting cartilage tissue between the skull plates. The swollen skull appears almost alien-esque, which emphasised the rarity and bizarre nature of this disease.

Today, this condition is known as congenital hydrocephalus and it affects about one in five hundred newborns. According to modern medical theories, congenital hydrocephalus can be caused by many factors including an infection in the uterus while the child was in the womb, the narrowing of the channels between ventricles, the incomplete closure of the spinal column, or when a child’s body is incapable of properly absorbing cerebral spinal fluid.(11) Hydrocephalus is usually diagnosed early on as swelling can be seen on a prenatal ultrasound while the child is still in the womb or during regular check ups when the head is measured to monitor the child’s growth rate. Early detection of any swelling in the brain allows the child to receive prompt treatment, meant to minimize the risks of brain damage. The most common surgical treatment today is to surgically inserted a shunt into the brain of a child after it is born, allowing the excess fluid to drain at a steady and controlled rate from the ventricles, to another part of the body (such as the abdomen or a chamber near the heart) where it can be more easily absorbed. The shunt remains permanently in the body for the remainder of the child’s life, typically requiring several more surgeries as the child grows older, in order to lengthen or unclog the draining tube.(12)

Notes:

1)Isbrand de Diemerbroeck. Trans. William Salmon. The Anatomy of Human Bodies; Comprehending the most Modern Discoveries and Curiosities in that Art, to which is added A Particular Treatise of the Small-Pox and Measles Together with several Practical Observations and Experienced Cures. (London, Printed for W. Whitwood, 1694) p208.

2) Nicholas Culpeper. Culpeper’s Directory for Midwives or A Guide for Women. (Lodon: Printed by Peter and Edward Cole, 1662) p241.

3) Robert Bayfield. A Treatise de Morborum Captitis Essentiis & Prognosticis. (London: Printed by D. Maxwell, 1663) p12.

4)Paul Barbette, M.D. Thesaurus Chirurgiae: The Chirurgical and Anatomical Works of Paul Barbette, M.D. (London: Printed for Henry Rhodes, 1687) p103

5)M. le Cat. Trans. Tho. Stack. “A New Trocart for the Puncture in the Hydrocephalus, and for Other Evacuations, Which are Necessary to Be Made at Different Times” Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775) Vol. 47 (1751-1752) pp. 267-272 . The Royal Society. P 267-269.

6)Ibid. 269-270.

7) Ibid, 271

8)John Friend. “A letter from Mr. John Friend to Dr. Sloane, Dated Oxon. Jul. 26. Concerning an Hydrocephalus. Philosophical Transactions” Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775), Vol. 21 (1699), pp. 318-322. Published by the Royal Society. P 319-320.

9)Ibid, 322.

10) Michael Underwood, A treatise on the Diseases of children with directions for the management of Infants from the Birth. (London: J Mathews, 1784)p 153.

11)Mayo Clinic Staff. Hydrocephalus. MayoClinic.com September 12, 2009. Date Access: August 16th, 2010. http://www.mayoclinic.com/print/hydrocephalus/DS00393/DSECTION=all&METHOD=print

12) Ibid.